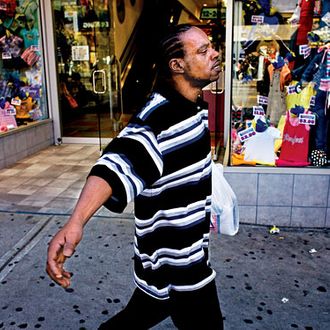

The first time I met Eddie Wise, he asked me for money. We were standing on East 189th Street in the Bronx, on a freezing afternoon in early 2007. My reporter’s pad in hand, I asked him if I could write a story about him. He made it clear he wanted to be paid. I can’t remember his exact words, but he probably used his favorite line: “Can you help me out?” I had to laugh. What did I expect? He was a professional panhandler; of course he was going to try to shake me down.

I explained that I couldn’t pay him for an interview but that I’d buy him lunch. He agreed. I think he was hungry — not only for food, but for the chance to unburden himself too. Overnight, he had become the most famous beggar in the Bronx. He’d been arrested at least twenty times in the prior two years for panhandling, and then — after discovering that panhandling had years ago stopped being against the law — he’d sued the city. Now he was about to get a check for $100,001.

His photo had already appeared in the tabloids, and he told me he couldn’t even walk down Fordham Road without strangers recognizing him: “They’re saying ‘Congratulations, man, you did the right thing. You used your head. You wasn’t scared. You’re the only one who beat the system.’” Drivers beeped at him. People he didn’t know stopped him on the street: “Yo, congratulations! That was you in the papers?”

He loved the attention, but it unnerved him too. Already his life had tipped upside down — and it would still be another six weeks before he got his check from the city. Every day or two, I went to the Bronx to interview him. About half the time, I’d find him on East 189th Street, between Webster and Park Avenues, where he’d be doing a hustle he called “parking cars”: helping shoppers find parking spaces, then feeding their meters in exchange for tips.

Other days, though, I couldn’t find him at all. He had no cell phone. We’d make a plan to meet on, say, Thursday at 1 p.m. and then he wouldn’t show up. Because it was raining. Or he forgot.

But when I did track him down, he loved to talk. Some things I learned: He had grown up in Sugar Hill, raised by his mother, who had paid the bills by cleaning rooms at the Carlyle Hotel. His father, known as Fast Eddie, had taken off when he was a baby, worked as a coke dealer, and made four trips to prison. Eddie, now 45, had started selling coke in the early eighties, and before too long he was smoking his own product.

He claimed to be clean now, and the entire block loved debating what Eddie Wise was going to do with his $100,000. Most were betting against him. “Everybody in the neighborhood is thinking that it’s going to be gone, that I’m going to be broke pretty soon,” he said. “Talking about, I’m going to spend $100,000 on crack. I’ll be dead by then! What do I look like, a stupid fool?”

The check finally came in late February of 2007 — and for Eddie Wise, nothing was ever the same. Now everybody was always asking him for money: family, friends, fellow panhandlers, anybody who recognized his face. That spring, I published my story about Eddie, made sure he got copies of the magazine, and never saw him again.

Every few months, though, he’d call me to check in. And every time he called, he’d always ask me for money. Not because he had already blown through his check, but just because he knew I’d always say the same thing: “Are you kidding? You’ve got more money in your bank account than I do!” We’d talk about his plans for the future, whether or not he was going to leave the city, who was begging him for money now. And he’d always insist he was staying clean.

Looking back on these conversations, which never lasted more than maybe five or ten minutes, I think the real reason he kept calling was to make sure that, even months and years after I’d finished writing my story, I still cared about him. Which I did. And I think he wanted to make sure that I hadn’t forgotten about him. Which was pretty impossible.

Just a few weeks ago, while walking along East 161st Street, I thought of him as I passed the bank branch where I’d gone with him the day he got his check — and where I’d had to teach him how to use an ATM since he’d never had a bank card before. I recalled that I hadn’t heard from him in a while, but I imagined — or at least hoped — he was okay wherever he was and that he still had a little money left.

Then I opened up the New York Post yesterday and saw him on page ten staring back at me, with a headline that he’d been found dead. According to the Post, he’d died completely broke, discovered by his wife in the “dank, rat-filled basement they shared,” bleeding from his nose; the cause of death was a hemorrhage because of “acute cocaine intoxication and hyperactive cardiovascular disease.”

It was the fate he’d feared from the moment we met, the ending to his story that he’d hoped would never be written.