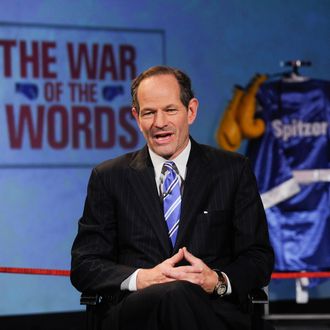

The New York City comptroller’s office is, objectively, an enormous step down from the governor of New York. Many New Yorkers, in fact, are probably only vaguely aware of its existence. That could change if Eliot Spitzer has his way. Despite only deciding to enter the race for comptroller this weekend, Spitzer has already alluded to an expansive vision for the position. “It is ripe for greater and more exciting use of the office’s jurisdiction,” Spitzer told the Times; in an interview with CBS This Morning, he said, “We can do so much in terms of shareholder power, in terms of corporate governance, in terms of protecting pensions, in terms of making sure the city’s money is invested well, spent well.”

What is Spitzer planning? Well, as comptroller, he would have oversight of the city’s five public pension funds, which hold the retirement money of teachers, police officers, firefighters, and other public employees. They’re big piles of money — about $140 billion in total — and managing them would give Spitzer the ability to be a huge pain in the ass for anyone else hoping to get a piece of the pension pie.

The New York City comptroller isn’t a Wall Street regulator — at least not directly. And Comptroller Spitzer would have only a fraction of the official prosecutorial power that Attorney General Spitzer had. But in some ways, he’d be more influential. Rather than simply suing banks for the same misdeeds as every other regulator, Comptroller Spitzer could play favorites with Wall Street, deciding which banks are given city contracts, which are subjected to higher auditing standards, and which are eligible for perks like the use of tax-exempt bonds to construct new headquarters. He wouldn’t be making these decisions alone — there are boards for these sorts of things — but he could certainly make his presence felt.

In his old Slate column, Spitzer wrote in support of using the leverage of pension over private-equity firms to push for stricter gun control. As comptroller, he’d be able to flex that moral muscle in any number of other situations. He could declare, for example, that the city would no longer invest in funds that owned shares of tobacco companies, casinos, or food chains that used GMOs. These powers have always existed among managers of large pension funds, but they’re rarely used. Spitzer, though, seems to relish the chance to bring them back into vogue. The size of New York’s pensions means that it “owns the market,” he said in another interview with WNYC this morning.

Spitzer could also bring back some of his old prosecutorial zeal, going after corporate executives and boards when they screw up. Interest-rate-rigging banks, crooked consultants, overpaid chieftains like Spitzer’s old nemesis Richard Grasso — all of these types could come under the comptroller’s microscope. Again, these powers have long existed but rarely been exercised effectively. (It took current comptroller John Liu three years to sue BP for the losses he claimed city pensioners suffered from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill.)

One person who would fear a Spitzer-led comptroller’s office is JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon. Earlier this year, Dimon narrowly survived a vote to keep the bank’s CEO and chairman roles consolidated. Spitzer said this morning that he’d try to split the roles, effectively putting Dimon out of half of his job. And while Liu pushed for (and failed to get) the split, Spitzer’s savvy media techniques and penchant for spotlight-grabbing could prove more effective. (Conceivably, they could also enrage banks to the point that they refused to do business with the city.)

Liu, though deserving of credit for his investigations into CityTime and 911 cost overruns, has been an erratic enforcer, going after entities as disparate as the board of Cablevision, the Central Park Conservancy, and the Department of Education’s high-school match process. There has been no coherent theme to his tenure — no motif of cracking down on certain corrupt industries or bad actors. Spitzer has signaled that he intends to change that and make the comptroller’s office a sort of shadow enforcement agency that will use its broad pension oversight powers to take on the city’s most entrenched and powerful capitalists. That’s good news if you like scrutiny of large financial firms, and bad news if you’re a banker.

Comptroller Spitzer would be equally unwelcome news for Mayor Weiner, Mayor Quinn, or whoever replaces Mayor Bloomberg next year. He told the Times that, as comptroller, he wants to become “the primary voice of urban policy — what works and what doesn’t work. It’s understanding that the audit power of the office is not just to figure out how many paper clips where bought and delivered, but to be the smartest, most thoughtful voice on a policy level.”

It may be a lofty vision, but Elizabeth Holzmann, the city’s comptroller from 1990 to 1993, says it’s not impossible. “The comptroller’s office can have a very important impact on policy, and should have one,” says Holzman. “Can it have the primary one? You know, it depends on the energy level, the goals, the ambition of the person in that position.”

Comptrollers are, inherently, closely involved in city policy. In addition to investing the city’s public pensions, they are tasked with auditing, vetting, and investigating pretty much anything the government spends money on. And because many comptrollers use the post as a stepping stone on the way to higher office (Spitzer presumably included), it’s typical for them to act as a thorn in the mayor’s side. But someone who aims to be the primary voice of urban policy doesn’t sound like a mere nuisance to the mayor. He sounds like a direct competitor.

Mitchell Moss, the Henry Hart Rice professor of Urban Policy & Planning at NYU’s Wagner School, agrees that Spitzer could transform the office. “This is a job which has a potentially vast capacity to influence the day-to-day life of government,” says Moss. Simply based on his prior time in office and “the nature of his persona,” Spitzer would be “much more aggressive as a comptroller than we’ve seen in recent history,” Moss says.

“He came to the job of attorney general and redefined it,” Moss adds. “He made the attorney general of New York into a national figure. And he would be a formidable presence locally and nationally as comptroller.”

If anyone could pull it off, it would be Spitzer.