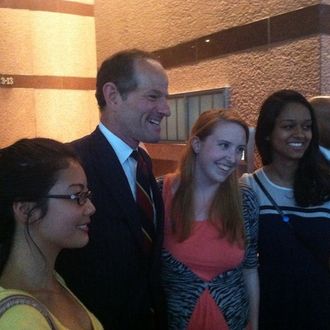

Eliot Spitzer rubbed elbows with a few dozen supporters over wine and bruschetta at a midtown restaurant on Wednesday evening as his last-minute candidacy for New York City comptroller picked up steam. The former Empire State governor and populist attorney general arrived at Sprig in the Lipstick Building on Third Avenue just minutes after the release of a Wall Street Journal/Marist poll that shows him leading Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer 42 to 33 percent among registered Democrats. A campaign photographer and event organizer high-fived each other at the bar when they caught wind of the numbers.

The party was supposed to help Spitzer gather some of the 3,750 signatures he’ll need by midnight on Thursday to secure a spot on the ballot, something of a tall order given that the city’s Democratic and labor Establishment is in lockstep behind Stringer. Indeed, Spitzer had to endure the swift departure earlier this week of two campaign operatives, Neal Kwatra and James Freedland, whose other clients apparently voiced disapproval. And those same forces are sure to challenge the legitimacy of Spitzer’s signatures, meaning he would do well to lock up thousands of extras to be safe.

A grinning Spitzer told reporters outside the restaurant that he took the “pressure applied to folks who had said they were going to participate” in stride. “That’s okay,” he said. “That’s hardball politics.”

Despite the encouraging poll numbers — Spitzer called them “comforting” — the candidate acknowledged that he and the small army of petitioners (some paid, some volunteers) currently headquartered in his father’s real-estate building on Fifth Avenue still had some work to do in the final 24 hours to get over the finish line. “I’m never confident,” he said. “In politics, you have to ask every day for the public’s support, for their understanding of what you’re trying to do.”

Early press accounts (Spitzer has seemed to do an interview on every news show imaginable since jumping into the race Sunday night) have tended to focus on the prostitution scandal that brought an early end to his already-disastrous tenure as governor in 2008. But Daily Intelligencer was able to sneak into the party and ask a few supporters what actually attracted them to the guy.

“I’ve been following him since his work as attorney general, and I was really proud of what he did as the Sheriff of Wall Street,” said Deborah Sanders, a business professor at Lehman College in the Bronx. “I admire that he was ahead of the crowd in terms of same-sex marriage and immigration reform, so I think he’s a great leader.”

Most of the attendees we talked to were elated at Spitzer’s reentry into politics, and thought the wave of comparisons with Anthony Weiner was way off-base. “Weiner’s was a display,” said Danielle Wanglien, a campaign volunteer and real-estate attorney in Manhattan, comparing the two scandals. “It was arrogance: look at me, on the Internet.” Spitzer, on the other hand, “is the most qualified for this position — overseeing and managing the city’s financial health — which has been his platform since he decided to go into politics.”

Wanglien, who is in her twenties, said many of her friends don’t remember Spitzer’s time as attorney general. Back then, she explained, Spitzer was “cracking down on financial institutions and being a great watchdog, which kind of predates what Cuomo has done and what Obama has done — predates the financial crisis, even.” As for the prostitution stuff? “I’m not married to the man, so I don’t really care what he does in his private life.”

Turnout at the party cannot exactly be described as robust. There were about twenty petition signatures at the door, a few of them pretty clearly invalid. A handful of petitioners were also stationed outside on the street, and seemed to accumulate a couple dozen more names over the course of the night. But another volunteer told me she had struggled to figure out how to get involved, eventually getting in touch with the campaign by responding to a Craigslist post for paid work collecting signatures (Spitzer said reports he was was shelling out $800 a day in desperation are untrue).

Perhaps intent on distinguishing himself from Weiner, who reportedly spent $54,000 on polling back in March ahead of a carefully orchestrated campaign rollout, Spitzer seemed to embrace the idea that this run was something of an impulsive move. “I didn’t do any polling before I got in this race, so this is the first set of numbers I’ve seen in any way, shape, or form,” he said. “It’s nice to see.”