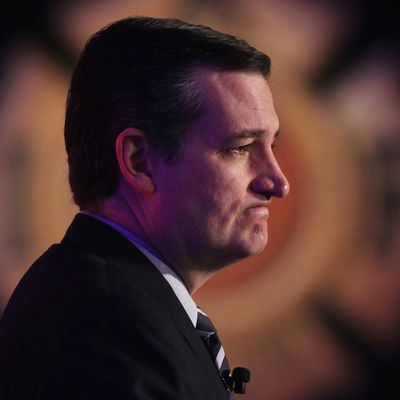

In an interview with CBS This Morning, Ted Cruz divulged that he used to love classic rock, but switched over to country because of 9/11. “My music taste changed on 9/11,” the presidential candidate said. “I actually intellectually find this very curious, but on 9/11, I didn’t like how rock music responded,” he said. “And country music, collectively, the way they responded, it resonated with me.” The inevitably boring interview question of what music a politician listens to has, in this case, yielded a fascinating and revealing answer.

Of course, the thing about classic rock is that it mostly didn’t respond to 9/11 at all, since most of it was written in the decades beforehand. To the extent that it did respond, it was in keeping with the patriotic spirit of the moment. Many of the biggest classic rock stars participated in “America: A Tribute to Heroes” ten days after the attacks. As the name of the event implies, the event was not exactly a Chomsky-esque exercise in attributing the attacks to blowback caused by imperial overstretch. The single biggest classic rock star, Paul McCartney, wrote a song the next day, “Freedom,” the proceeds of which he donated to families of the victims and the NYPD.

It is true, however, that, in general, rock stars did not reach the jingoist heights of their country brethren. The rockers were mourning victims and celebrating freedom; country stars were demanding blood. That was a real partisan cultural divide. That divide overlaid a related cultural trend during the Bush years, during which the Republican Party defined itself as the representative of “real America,” as represented by pickup trucks, NASCAR, small towns, country music, and the most rigidly nationalistic forms of patriotism. It is easy to forget now just how important (and frequently ridiculous) heartland cultural authenticity, and corresponding disdain for decadent urban intellectual elites, was to Republican Party identification at the time.

And here is where Cruz’s musical conversion reveals something interesting about his character. Raised by a militant conservative for a career in political activism, Cruz initially channeled his ambitions through formal education, which bred an intense intellectual snobbery. People who knew him recall Cruz asking them about their IQ and refusing to study in grad school with anybody who didn’t attend Harvard, Yale, or Princeton (a cutoff that only a Princeton grad would define).

At some point in his career, this snobbery became not only unnecessary but a hindrance to advancement. In George W. Bush’s Republican Party, populist authenticity, not Ivy league credentialism, was the cherished social currency. That Cruz was both willing and able to reorder his musical preferences to conform to the party line in the cultural struggle is an incredible testament to his personal willpower.

As often happens with Cruz, his professed fanaticism raises the question of whether he actually believes what he claims. Has the good senator actually stopped listening to the classic rock he spent decades enjoying? If so, does he ever feel tempted to listen to his old favorites, or has he internalized the party line so thoroughly that the mere sound of “The Wall” or “Beggar’s Banquet” and its decadent cosmopolitan liberalism now sickens him?

Alternatively, if Cruz is making this up — if he maintains a private stash of pre-9/11 classic rock that he indulges only when alone or in the presence of his most trusted confidantes — it would be, in a way, even more impressive. It would be attractive to imagine Cruz as the mirror-image equivalent of Cold War–era Soviet citizens locked furtively in his apartment, listening to taped-over bootleg Beatles cassettes, hoping no loyal party members overhear. Keep on rockin’ in the free world, Senator Cruz.