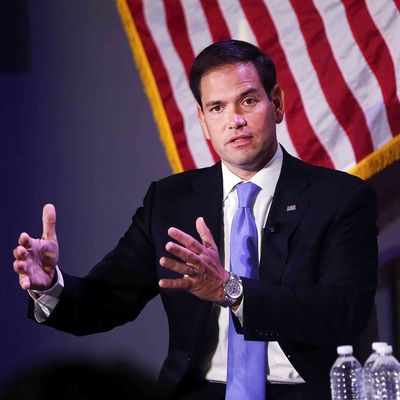

Cycles in presidential campaigns begin with hopeful conjecture, outright lies, blind tabloid items that can’t ever be proved or disproved. This week the Marco Rubio cycle began. Marco Rubio is now the “front-runner” for the Koch brothers’ support and cash, the New York Daily News reported yesterday morning, citing a source “who ran into David Koch at a recent event in Manhattan.” That sourcing sounds pretty shaky — David Koch has never seemed like someone who blurts out his political plans to the restroom attendant, though, who knows, people always surprise you — but of course it’s hard to imagine that the item isn’t true. By the time Rubio and Donald Trump arrived in Las Vegas yesterday to speak in separate events at the same time, the hype seemed almost anxious: “High Noon Out West Between Trump and Rubio the Kid,” the Times had announced this morning. Trump has recently lost interest in insulting Jeb Bush and started insulting Rubio. As an insult comic, the Donald has lately been somewhat overrated, and he has taken a grasping line on Rubio: that the younger man was sweaty and needed to gulp water during the second presidential debate, that this marks him as a lightweight. Hydration issues aside, that Trump has trained his own sights on the Floridian (much as the press has, and evidently the Kochs) has helped to confirm that the party’s outsider energies may be dissipating a bit. In this new phase the race’s pivotal figure may no longer be Trump, the most bombastic candidate, but Rubio, the most talented one.

If the Times is right and Las Vegas was the site of the showdown, then the symbolism isn’t especially auspicious for the casino magnate turned populist politician. Trump is inescapably the candidate of the Strip, of the Vegas illusion, of everything about the city that feels gaudy and impermanent. Rubio can lay claim to a more human experience here. As a child Rubio spent six years living in a working-class Las Vegas neighborhood while his father worked here as a banquet-hall bartender — “behind a portable bar,” his son likes to say in his speeches, and that portable carries some feeling for the precariousness of working-class life. The casinos offered little for kids, and so the Rubio immigrant parents took him driving past the grand Vegas mansions, Liberace’s among them, explaining to their kids that this kind of success was possible for them in this country. As Nevada’s politics have matured — as the place has become increasingly Hispanic and increasingly pivotal, as the state’s key figure has become Brian Sandoval, the Hispanic Republican governor — they have left behind Trump’s great themes, of the certainty that America will always win, and moved right into Rubio’s, of whether the promise of the American Dream that the country holds out to immigrants is still possible.

During the 2008 campaign there was much worrying over the nearly complete whiteness of Iowa and New Hampshire — the way the early primary states might suppress the influence of black voters in the Democratic primary. But this time the singular hue of Iowa and New Hampshire has had a different effect. It has kept off-screen the Republican Party’s essential demographic challenge, of winning something other than the votes of white men. Rubio’s argument is that though immigrants can cause problems, they also supply a restorative aspiration and optimism. That is just as much the modern Nevada story as it is Rubio’s own.

Step back from today’s “showdown,” take a slightly longer perspective, and it is startling how well the race has gone for Rubio so far. One of the two early favorites for the nomination, Scott Walker, has already abandoned the race; the other, Jeb Bush, is struggling badly. Even though the early campaign has emphasized immigration, the issue on which Rubio is most alienated from the mainstream of the party, he has not taken a direct hit, in part because he has run a low-key and noncombative early campaign, and it seems likely that as Rubio comes to the fore the energies around the issue may fade, at least a little bit. Analysts have noticed how rapidly Rubio is catching up, both in the polls and in the betting markets.

Meanwhile, Rubio’s campaign has been filled with small-scale genial deftness. Asked on Fox News about the Black Lives Matter protests, he called it “a legitimate issue” and said that a professional African-American friend of his had been stopped by police “eight or nine times” in the past 18 months for “no legitimate reason.” Far more than Bush or Trump, Rubio has seemed to grasp that the essential challenge of the current election is not only ideological but also generational: a battle over whether Hillary Clinton can complete the long post-baby-boomer project, which moved through her husband’s presidency and Obama’s, of moving the country’s politics to the left in ways that reflected social transformations of the ‘60s. “Turn the page on yesterday,” Rubio urged, when I saw him in New Hampshire on Wednesday. This is the obvious message that Republicans would want to take into a general-election campaign against Hillary Clinton. It is also one that, among the leading Republican candidates, uniquely suits Rubio.

Rubio’s crowds are still not as big as Trump’s, and he has raised much less money than Bush has. That he has so far stayed away from the center means that the senator is still a somewhat vague and soft-focus candidate, of hope but not clear edges. He still has not effectively defended his record on immigration to his party’s base, has not been forced to reconcile his dreamy budget with reality, has not had to defend his militarism against charges that it is naïve, or had to prove that his social conservatism was not badly outdated. He has never attacked. Even now you see the idea of the candidate more clearly than you see the candidacy itself.

The most interesting political question of the past four years — whether the right-wing insurgency represents a basic reordering of conservatism or simply an expression of its anger (the Tea Party: Revolution or Evolution? Discuss) — has not yet been resolved, and as frequently as Rubio is compared to Obama, he has to map less-certain terrain. In Washington conservative politics has become an identity demonstration as much as anything, and if that is the mood in the early primary states by the winter, the senator from Florida probably can’t win. And so even as he surges, his campaign has an interstitial feeling. Rubio avoids conflict, talks hopefully about the future to the elderly, assembles positions on which he might move either right or left. And, as Trump noticed, he minds his hydration, since in a marathon the last thing you want is to be beset by thirst.