This weekend, leaders from 196 countries approved the first global agreement to limit greenhouse-gas emissions in human history. The pact is a triumph of international diplomacy shared by diplomats across the planet. It also represents the culmination of a patient strategy by the Obama administration that unfolded over years, and which even many sympathetic journalists long dismissed as fanciful. Obama’s climate agenda has lurked quietly on the recesses of the American imagination for most of his presidency. It is also probably the administration’s most important accomplishment.

1. Climate change is different from other issues. The Obama administration has enacted important reforms to prevent a Great Depression, reform health care, overhaul the financial system and education, and craft important breakthroughs with Iran and Cuba. But climate change occupies a category of its own. The damage from climate change is irreversible. Melted glaciers cannot be easily refrozen; extinct species cannot be reborn; flooded coastal cities are unlikely to be rebuilt. Action to mitigate climate change has an urgency nothing else can match.

2. Paris is a BFD. In 1990, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change called for a global treaty to limit the effects of greenhouse-gas emissions. The United Nations spent the next quarter century trying, and failing, to organize effective world action, despite increasingly dire warnings of massive, deadly, irreversible change that would threaten human life as we know it. An extremely simple conclusion can be drawn from this timeline: A worldwide-climate-change agreement is incredibly hard to do. If the Paris agreement were a simple matter of serving some nice French meals and writing some vague feel-good goals, it would have taken less than a quarter-century to happen.

3. Paris does not exist on its own. The Obama administration’s climate strategy began with a massive infusion of $90 billion in green-energy financing in the stimulus, which set off a wave of new investment and research in wind, solar, storage, and other measures. Obama signed the stimulus in his first month in office, and hoped it would launch the passage of a cap-and-trade law and an international climate agreement in Copenhagen. But the strategy derailed badly. The 2009 negotiations in Copenhagen virtually collapsed, and cap and trade was blocked by a coalition of a handful of Democrats from fossil-fuel-producing states and almost the entire Republican Party.

At that point, Obama’s climate strategy looked well and truly dead. Instead, the administration forged a different path. It used its existing regulatory power under the Clean Air Act to devise innovative new regulations to control greenhouse-gas emissions across the economy. The reductions it could wring from its regulatory powers gave the administration the leverage to negotiate a bilateral agreement with China in 2014. The U.S.-China agreement broke a deadlock between the industrialized West and the developing world that had paralyzed all previous international negotiations. The plunging costs of solar and wind energy, plus new innovations in storage and other clean-energy technologies, made it suddenly plausible for governments across the world to transition their energy systems.

4. Climate action is hard everywhere, but especially so in the United States. Climate change is a devilish issue for any politician, since the costs of action are heavily front-loaded, while the benefits lie far off in the future. Two features of American politics compound the difficulty. The United States has a somewhat unusual form of government in which the legislature and the executive branch can be controlled by opposing parties, which means that the president can negotiate a deal with other world leaders without being able to guarantee his government’s support for the result. Any formal treaty requires the approval of two-thirds of the Senate, which is itself an undemocratic body giving disproportionate representation to citizens from small, rural states.

Worse still, the United States is the only country in the democratic world that has a major party that questions the scientific theory of anthropogenic global warming. Conservative parties abroad often take more market-oriented, or perhaps less-ambitious, approaches toward limiting carbon emissions. But the stance taken by the Republican Party, in which respected leading figures endorse kook conspiracy theories, is simply not heard anywhere else. And even the Republican leaders who hesitate to openly endorse conspiracy theories utterly dismiss any international action to limit greenhouse-gas emissions.

The interplay of both these dynamics has placed the Obama administration in a singularly difficult position. The U.S. is the world’s largest historic emitter of greenhouse gases, and the leader of the free world. Yet its political system makes the passage of any legally binding international climate treaty utterly inconceivable. The Paris agreement had to work around this obstacle. The result was highly innovative: a collection of pledges from nearly every country that, without formal legal force, nonetheless took on diplomatic weight.

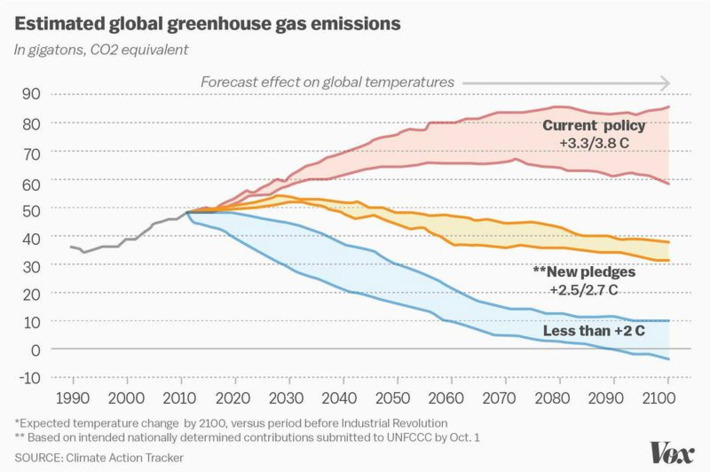

5. Success begets success. Much of the coverage of the Paris agreement has struck a sober note, depicting the agreement as a “first step,” or cautioning that “now comes the hard part.” All the caveats are perfectly true. The pledges amount to about half of the reductions necessary to bring emissions down to a level scientists consider safe, as this chart compiled by Brad Plumer shows:

Mitigating climate change is not a simple yes-no proposition. Holding temperature increases to 2.5 or 2.7 degrees Celsius may not be as good as holding them below 2 degrees, but it’s much better than holding them to 3.3 or 3.8 degrees. What’s more, the structure of the agreement is designed to produce additional reductions over time. At the urging of the U.S., countries are required to reconvene every half-decade and consider tighter reductions.

Obviously, such reductions will only happen if they are economically feasible. But recent history shows that political willpower and innovation feed off each other. Support for green energy in the United States (through the stimulus), Europe, China, and elsewhere spurred research and investment that have triggered a revolution in affordable solar and wind power, among other green-energy technologies. The green-energy revolution has made what was unaffordable in 2009 suddenly affordable. It is realistic to assume that the momentum from Paris will continue the virtuous cycle of political willpower and market innovation — the massive new market for reducing carbon emissions will spur more investment that will produce newer and more efficient technologies, allowing elected officials to make deeper emissions cuts.

It is hard to find any important accomplishment in history that completely solved a problem. The Emancipation Proclamation only temporarily and partially ended slavery; the 13th Amendment was required to abolish it permanently, and even that left many former slaves in a state of terrorized peonage closely resembling their former bondage. The Lend-Lease Act alone did not ensure Great Britain would survive against Nazi Germany; the Normandy invasion did not ensure the liberation of Europe. Victories are hardly ever immediate or complete. The fight continues and history marches on. The climate agreement in Paris should take its place as one of the great triumphs in history.