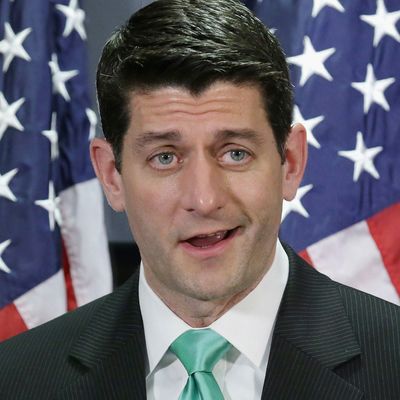

Paul Ryan’s shadow campaign for the presidency is well under way, and the visible portion peeking above the surface — message videos and gravitas-conferring overseas trips — conceals a larger whisper campaign submerged beneath the surface. If Donald Trump fails to win a majority of pledged delegates on the first ballot, and if Ted Cruz fails to organize a majority on a subsequent ballot, a disorderly and panicked party would almost automatically turn to its recognized leader as the candidate. Alternatively, should either Trump or Cruz win the nomination, Republicans running down-ballot will need a less toxic brand. In which case, Ryan will assume his role as de facto party leader, supplying a friendlier-sounding message for Republicans in blue and purple states.

That message is previewed in today’s New York Times, which reprises the familiar themes Ryan has sounded for several years. Some of the differences between Ryan and the declared candidates are real. Unlike Trump and Cruz, Ryan supports the party’s business wing on international trade and immigration. He is pragmatic about political messaging and tactics, and understands that doomed kamikaze legislative maneuvers or gratuitously insulting key demographic groups ultimately sets back the conservative cause. Also on display in today’s story is Ryan’s well-honed talent to conjure an imagined, impossible version of his own policy agenda and present it as reality.

The magical-realism version of the Ryan platform involves heaping doses of empathy and wonkishness. As always, the evidence for this lies not in any concrete commitments but in promises lying somewhere over the horizon. The key passage from today’s Times story: “For example, if the Republican nominee does not provide an alternative to the Affordable Care Act — something Republicans have failed to do since it passed in 2010 — Mr. Ryan intends to do so, just as he will lay out an anti-poverty plan.”

Note the “intends to,” a phrase that captures Ryan’s uncanny ability to have his assurances taken at face value. Republicans have been promising that they were on the cusp of unveiling a party-wide alternative to the Obama administration’s health-care reform since the debate began in 2009, but they have never quite managed to do so. Republican alternatives to Obamacare have lain just over the horizon for half a dozen years, and oddly enough, the pace of their imminent unveiling appears to have increased. Consider a small sampling of the recent time frame. In January 2014, Ryan promised he would develop a Republican plan that year. By March, the Washington Post was reporting the unveiling of this plan as a fait accompli:

The plan never came. In April of that year, it was still in development but due to come out extremely soon. “Sen. Marco Rubio and Rep. Paul Ryan are collaborating on an Obamacare alternative and could announce the proposal as early as this month, according to Republican sources,” reported the Washington Examiner.

The next year, Ryan renewed his commitment to reveal his plan very, very soon. In February, 2015, Ryan announced the plan would be out by the end of March. By the end of March, there was still no plan, but Ryan did declare that Republicans “must have a plan to replace Obamacare by late June.” June came and went, and summer turned to fall, and fall to winter. By December 2015, Ryan proclaimed the need for a Republican plan “urgent.”

By January of this year, Ryan — asked if the promised plan would come to a vote — said, “Nothing’s been decided yet.” Later that month, his spokesperson was insisting that many steps had yet to take place, and it was out of Ryan’s hands. “As the speaker has said many times, committees, not leadership, will be taking the lead on policy development,” Ryan spokesperson AshLee Strong told the Washington Post. “The next step will be forming committee-led task forces that will hold listening sessions with Republican members … The task forces will then develop the specific policy.” Task forces, committees, listening sessions — there is just so much to do.

The reason the dog keeps eating the Republicans’ health-care homework is very simple: It is impossible to design a health-care plan that is both consistent with conservative ideology and acceptable to the broader public. People who can’t afford health insurance are either unusually sick (meaning their health-care costs are high), unusually poor (their incomes are low), or both. Covering them means finding the money to pay for the cost of their medical treatment. You can cover poor people by giving them money. And you can cover sick people by requiring insurers to sell plans to people regardless of age or preexisting conditions. Obamacare uses both of these methods. But Republicans oppose spending more money on the poor, and they oppose regulation, which means they don’t want to do either of them.

Conservatives do have ideas, of course. They would like to deregulate the insurance industry, letting insurers skim out healthier customers and charge higher prices to people who are sick. And they’d let insurers sell much skimpier plans that only cover catastrophic expenses, leaving customers to pay for their own treatments. As for funding, most conservatives do favor eliminating the tax deduction for employer-provided health insurance, which is a source of funding. The problem is that eliminating that deduction would unravel the entire fabric of employer-based insurance, threatening the status quo for most working-age Americans and their families. Throwing nearly everybody who has private insurance onto barely regulated markets, with only a meager tax credit to fund a crappy, catastrophic plan, would be politically disastrous. So Republicans cannot and will not present anything like a detailed party-wide alternative to the status quo.

A similar reason prevents Ryan from detailing his “anti-poverty plan.” In this case, the problem is Republican fiscal math. Ryan and his party are ideologically committed to massive tax cuts — indeed, Ryan reiterated not long ago that he would refuse to support any tax-reform plan that did not relieve the burden on high earners. They are likewise committed to maintaining Social Security and Medicare for anybody 55 and up, which by definition rules out any cuts to their budgets over the next decade. Ryan has also proven unwilling to implement deeper cuts to the discretionary budget — the funding stream for agencies that, for the most part, are not redistributing money from rich to poor, the largest being the Department of Defense — which is why he has twice agreed to raise the funding caps on that pool of money. That is why Ryan’s budget relies on massive, disproportionate cuts to spending programs that help the poor. Sixty-two percent of the cuts in the Republican budget come from programs aimed at helping people with low incomes. (Those programs account for less than a quarter of all program spending in the federal budget.)

Ryan has gone to enormous lengths to demonstrate to the national media that he truly and deeply loves poor people and wants what is best for them. But however Ryan feels about poor people in his heart, the boundaries of his policy commitments lead inescapably to the result that he is going to massively reduce the amount of money the government spends on helping poor people. If Ryan didn’t share these priorities, he wouldn’t be the leader of the Republican Party, and insiders would be casting their eyes somewhere else for an alternative to Trump and Cruz.

Now Watch: