For the sixth time in the last seven presidential elections, Democrats won a plurality of the presidential popular vote on November 8 (Hillary Clinton’s lead over Donald Trump continues to grow as those last West Coast ballots are counted; it’s currently at over 1.6 million votes, or 1.3 percent of the total).

Yet Democrats are in a decisively minority position when it comes to wielding power in the United States. They lost the presidency via the Electoral College. They are a minority in the Senate and facing a terrible Senate landscape in 2018. They are a minority in the House with little hope of retaking it before the next cycle of reapportionment and redistricting after the 2020 census. And at the state level, their weakness is even more evident. Only 16 of the 50 governors are Democrats (and that assumes Roy Cooper will eventually be named the winner in North Carolina). Republicans control 68 state legislative chambers as opposed to 30 controlled by Democrats. Republicans hold “trifectas” (control of the governorship and both legislative chambers) in 25 states as compared to 6 for Democrats.

Putting it all together, according to an index of partisan electoral strength put together by Real Clear Politics’ Sean Trende and David Byler, Democrats are in the worst shape they have been vis–à–vis Republicans since 1928.

The disconnect between the Democratic plurality (and near-majority) in the presidential popular vote and a weak performance that seems to get weaker the further down-ballot you go, is not, it is important to understand, the function of ticket-splitting. Best we can tell, ticket-splitting continued its steady decline this year, as is best shown by the fact that there was absolutely no difference between the states carried by the two parties’ presidential and Senate candidates (the first time that has ever happened).

So the overall partisan imbalance between the party that keeps winning the presidential popular vote and the party that keeps winning everything else is entirely the product of a system that systematically violates the supposedly sacrosanct principle of voter equality. As right-wing talk-radio types love to insist, the United States is a republic, not a democracy. And that has created an abiding problem for the Democratic Party.

Voter inequality is most obvious and deliberate in the constitutional setup (which cannot be changed by amendment) of the U.S. Senate, which gives California’s 38.8 million people and Wyoming’s 563,000 the same representation in the upper chamber. As one recent study estimated, states representing 17 percent of the U.S. population could in theory control the Senate. The superior power of small states via the Senate is enhanced by the Senate’s exclusive power over nominations and treaties, and by the custom of allowing 41 senators to veto regular legislation via the filibuster (which could soon be abolished, however).

The Senate’s small-state bias is projected into presidential elections, of course, by the Electoral College, which then typically compounds it by making smaller “battleground states” like New Hampshire, Iowa, and Nevada disproportionately important.

The House is allegedly the “people’s chamber,” and the body designed by the Founders to most directly represent popular sentiment, within the bounds set by the Senate, the courts, and the Constitution itself. But the role of the states in drawing House district lines — with no constitutional limits on political gerrymandering — has significantly eroded its function as the democratic wing of the federal government. To the extent state governments tilt Republican — as they have in recent years — that bias is also injected into the House formula. And that is one reason why in this latest election it may have required something like a Democratic super-majority — or a 10-point margin in the national House popular vote — to flip the lower chamber.

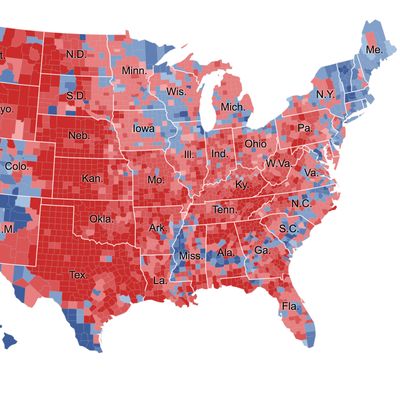

Another reason for the Republican advantage in the House is that Democrats are increasingly concentrated in urban areas that reduce their efficiency as a voting bloc. Many Democratic votes are “wasted” in jurisdictions they already control. Again, that adds to voter inequality.

Since the number of state governments controlled by each party is widely viewed as a signifier of power, the persistent pattern of Republicans winning 30 states and Democrats 20 in presidential elections has turned into a big GOP advantage in state capitals. In addition to the other factors boosting GOP power in the states, 36 states hold gubernatorial elections in midterms when Republican-leaning demographic groups are significantly more likely to vote. State governments are important in their own right as policy-making bodies, and aside from their projected power into the federal system via redistricting, they also supervise elections and (especially with a Supreme Court, a presidency, and a Congress indifferent to if not hostile toward minority voting rights) participation in elections.

So for all of these interlocking reasons, the half-or-so of the American citizenry that is prone to support the Democratic Party and its more-or-less progressive agenda and ideology is and may continue to be underrepresented at the federal level to the point of powerlessness, and confined at the state and even local levels to enclaves that contain an awful lot of people but exert limited clout. And all this is totally aside from the extrinsic factors that place a thumb on the scale for Republicans, such as their support from business and financial interests and our currently uncontrolled system of campaign financing.

What can Democrats do about this situation?

Well, there are really just two options. The first is to pursue reforms that make our system more democratic. Absent the power to remake the Constitution, the three most promising avenues for democracy promotion are the neutralization of the Electoral College via the National Popular Vote Initiative (an interstate compact wherein states controlling a majority of the Electoral College agree to name electors representing the popular-vote winner), redistricting reform to restrict or eliminate partisan gerrymandering (a tricky business but still possible), and grassroots and legal pressure to protect voting rights.

If Democrats cannot rebalance the playing field significantly, then they are just going to have to find ways to break out of their geographical isolation and win majorities in more states. How to do so is a topic too large for this post. But there is a preexisting and long-standing division of opinion between Democrats who think winning in less urban areas requires a more centrist positioning on issues, and those who believe economic populism is the key to that (and every other) political kingdom. Democrats need to choose a strategy by 2018. Time is already a-wasting.