Because we live in a bubble, but what a bubble. Because we know where Trump lives, and how best to get under his skin, too. Because Chumley’s is back and the Park Slope Food Co-op will never change. Because we’re not disrupting death, we’re turning it into art. Because La Guardia is actually going to get a lot better. Because even our hospitals are into trendy dining. Because the coolest rapper in America is a queer woman from Brooklyn and the No. 2 college-football recruit is from there, too. Because you can now drink before noon on a Sunday. Because Ken Thompson and Bill Cunningham worked until the very end. Because weirdos and artists and, most of all, immigrants will never stop wanting to call this city home.

N0. 1 | Because The City Is Still Ours.

The city was always an asylum. On television on Election Night, the word they used was bubble. But what a bubble.

New Yorkers woke up on November 8 in what seems now like a fairy-tale fog, convinced, as ever, that the future belonged to us. By midnight, the world looked very different, the country very far away (and the future, too). Eighty percent of us had voted against the man who won, and 80 percent, it seemed, were already hatching plans to leave — for Canada or Berlin or anywhere else we imagined we could live safely among the like-minded. That was when the text messages began coming in from old friends in Wisconsin and Texas and North Carolina and Missouri. They were watching the same returns we were, in the same apocalyptic panic, and all making desperate plans to come to New York. For them, the city was still the same fairy tale.

Read the Full Essay →

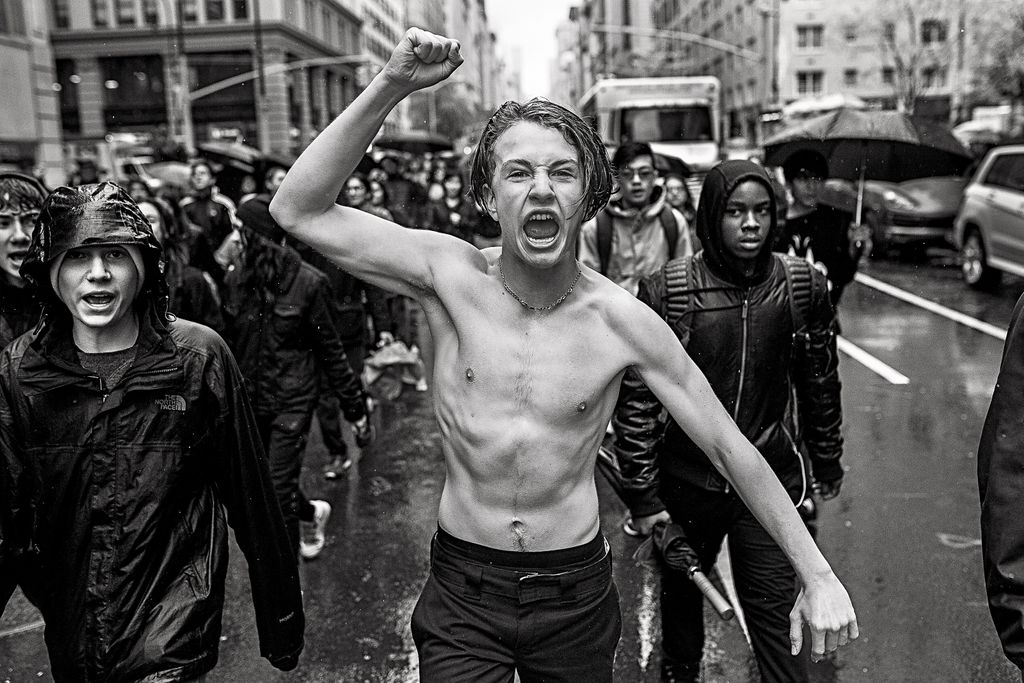

No. 2 | Because Even Our Protesters Are Precocious.

It’s a Sunday afternoon, and outside the Greenwich Village Stumptown, the dissidents have assembled. They have rosy cheeks and glossy hair, and four of the five are tenth-graders at Little Red School House, a progressive private school where, in the throes of citizen despair during a first-period class on 3-D art (“It’s like sculpture therapy”), Claire Greenburger, Leilani Sardinha, and Loulou Viemeister had decided that something had to be done. It was the Thursday after Trump had been elected. “I saw all of my teachers cry,” says Claire. The three girls reached out to friends Jane Brooks and Bennett Wood (who goes to Calhoun but had met Loulou at a “social-justice camp” in Vermont), and by Friday they had created a Facebook page titled “NYC School Walkout Love Trumps Hate,” calling for kids to walk out of class and storm Trump Tower at 10:30 a.m. the following Tuesday. “We thought there would be a couple hundred kids,” says Jane. Then Occupy Wall Street linked to the page. Suddenly, thousands of people were “interested.” “We were like, Oh my God, what is happening?” says Claire. “By Monday, everyone was talking about it.”

That included the school administration, which insisted the protesters get their parents’ permission. “My dad told the vice-principal, ‘She doesn’t need my permission. This is civil disobedience!’ ” says Loulou. “He was like, ‘I’ll pick you up from jail tomorrow.’ ”

“My dad handed me a lawyer’s phone number,” adds Jane.

Despite the fact that it was raining and frigid, the protest pen near Trump Tower was filling up by the time the organizers arrived. “Bennett and I ran into the street and were like, ‘Okay, everyone, into Fifth Avenue,’ ” Loulou explains. “The police didn’t really know what to do,” Claire says, grinning. Leilani agrees. “It was completely illegal.” The NYPD started guiding traffic away as the throng marched all the way to Washington Square Park. Says Claire, “It went better than we could have ever imagined.”

Not that the protest was perfect. “In the events that we’re planning in the future, more diversity would be cool,” says Jane, aware of the irony of the walkout’s being planned mostly by a crew of privileged kids. Nor do they harbor illusions of what a protest can accomplish. “We’re not going to change the fact that Trump is president.” But they take heart in the fact that among millennials, Hillary Clinton won by a landslide. “Watch yourself, Trump,” Jane says. “Because we’re voting next.” —Alex Morris

No. 3 | Because Our Streets Defy Dictators.

From the imperial fora of ancient Rome to Buenos Aires’s Plaza de Mayo, authoritarian regimes have always found big, ceremonial spaces both dangerous (because they concentrate so many people in one place) and ideally suited to surveillance and propaganda (for precisely the same reason). New York has no obvious place of assembly, so the streets serve as a movable piazza. Protests have begun on the Columbia campus, in Washington Square, in Central Park, and at the United Nations; they’ve taken over a tiny office park most New Yorkers had never heard of and branched out over the Brooklyn Bridge. This lack of a focus embodies the essential New York values that the new administration appears so eager to crush: the city dwellers’ refusal to be corralled or homogenized. —Justin Davidson

No. 4 | Because We Know Where Trump Lives.

It is a lesson learned from my father, a lifelong New Yorker (1920–1995), a bit of big-city wisdom imparted as we drove through our home borough of Queens sometime in the early ’60s. We crossed the then–newly completed Long Island Expressway and entered the glittery environs of Jamaica Estates, where the trees were more stately and the houses more grand than our modest GI Bill dwelling. As we passed one nicely appointed home, my father slowed the family Fairlane.

“There’s where Trump lives,” Pop said, with a shake of his head. A proud member of the New York United Federation of Teachers, my father always disliked the Trumps, especially Fred C. Trump, the family patriarch and enabler, whom Pop believed to be an arch–union buster. It wasn’t that my father was planning to picket the place. He just wanted Trump “to know that I know where he lives.”

It is no big deal to know where a Trump lives these days. Like at Trump Tower, home to the presidential penthouse, the guy writes his name in giant gold letters over the door the way dogs piss on trees. If you miss it, just look for the new normal of screaming protesters, edgy cops outfitted with automatic weapons, and the unsettling feeling that sooner or later something’s gonna give.

But I never took my father’s lesson to be restricted to a physical address. It is a statement of a deep sense of knowing gained through proximity and long experience. That is why the citizens of our metropolis have a special responsibility as The Donald’s double-chinned shadow falls increasingly upon the land. No matter how ardently his anti-cosmopolitan, anti-Enlightenment supporters attempt to ignore the fact, Trump remains a New Yorker, for better or worse, one of us.

This brings up a corollary thought train. As anyone can tell, Trump’s bullheaded insistence on running his transition out of midtown has only further galvanized local resentment against him. After all, the demonization of immigrant grandmas and the enabling of neo-Nazis is one thing. But closing down crosstown streets during the Christmas rush, costing city taxpayers more than a million dollars a day to protect a pol who got less than 10 percent of the vote in Manhattan and the Bronx — this is another level of insult. Then again, Trump could be doing this on purpose. Punishing the hometown for not loving him enough. That would be a prick thing to do, a decidedly New York prick thing. A Trump thing. That’s what my father meant: When you know where someone lives, don’t ever take your eyes off him. —Mark Jacobson

No. 5 | And Because One Upper West Side Apartment Complex Evicted His Logo.

No. 6 | Because the Mayor Finally Found a Worthy Adversary.

A week after the election, Mayor Bill de Blasio, who had attacked Donald Trump’s deportation proposals as “dangerous” and “un-American” and said his support from the KKK was “disgusting,” ambled into a golden elevator at Trump Tower for an audience with the president-elect. The mayor wasn’t there to eat crow. “I don’t forgive him some of the things he said on the campaign trail at all. I think they were destructive,” de Blasio said recently. He reminded Trump of “the human consequences of these words and deeds.” They discussed the NYPD, which will now be devoting its energies to protecting Trump Tower; de Blasio pointedly mentioned that some 900 members of the force are Muslim-Americans. Afterward, he vowed publicly to “stand up for anyone who because of any policy is excluded or affronted.” De Blasio’s warnings about income inequality and his calls for a coalition of progressive mayors have sometimes been ignored or even mocked by fellow Democrats. Now, though, his voice may prove essential. “I think there is going to be a lot of common action to protect immigrants in our cities,” he said. Along with other mayors, de Blasio has promised to obstruct any push for mass deportations by refusing to turn over personal data and expanding legal services for immigrants. City Hall is preparing in case Trump tries to impose pressure through massive cuts in city funding. “Whatever happens in Washington, we ain’t changing,” de Blasio said. “I think we have a chance to be a living example of a pluralistic society.” —Andrew Rice

No. 7 | Because Three James Madison High School Alums Will Get America Through This.

Had they overlapped, these nerds would definitely have sat at the same table in the cafeteria. Ruth Bader Ginsburg (class of ’50), Bernie Sanders (’59), and Chuck Schumer (’67) all wrote for the newspaper at James Madison High School, and all three were involved in sports (Ginsburg chipped a tooth baton-twirling). And, no surprise, they were demonstrated leaders: Sanders was class president, Schumer was valedictorian, and Ginsburg was … treasurer of the Go-Getters Club. In the postelection hangover, the Jewish Brooklynites have emerged as never-more-necessary stalwarts of progressive politics. —Kaitlin Menza

No. 8 | Because only a thrice-married, sex-crazed, germophobic, tabloid-bred, ex-casino-owning, condo-peddling, bankruptcy-surviving, playacting Darwinian capitalist New York real-estate billionaire reality-TV host, who demands to be adored, cannot be criticized, takes no responsibility for anything, never apologizes, and managed to convince half of America, mostly through Twitter, that he’s a straight-talking, swamp-draining friend of the common man, with various foolproof yet-to-be-disclosed solutions for how he can make everything great again, at least for people like them, could shock even the most over-it New Yorkers out of their complacency.

No. 9 | Because Kate McKinnon Didn’t Make a Joke.

When Kate McKinnon took the HRC reins from 2008’s Amy Poehler on Saturday Night Live, she applied a sharper edge to her mark: There was not a speck of Clinton’s Methodist good girl in McKinnon’s version, only the bloodless ambition and raw drive and robotic mania. It was, frankly, a little mean. Mean but glorious and gleeful. McKinnon amped it up, rolled around in it: Her cackling Hillary slept in her pantsuits, popped Champagne and victory-danced after the pussy tape was released, and pretended tears of vulnerability before reminding us — about any of Clinton’s setbacks, really — “Get real, I’m made of steel, this is nothing.” McKinnon made hay of the glowering specter of female threat. She was unapologetic and tough and hilarious and so uncool she was almost cool and she was, it felt in those last few weeks of sketches, probably going to be the president. And then Hillary lost.

And so McKinnon got onstage the Saturday after the election, sat at a piano in her defiant white pantsuit, and performed Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” eulogizing the singer who had died that week alongside the dream of a Hillary presidency. As she sang the final verse, her voice shaking, her eyes shining — “And even though it all went wrong / I stand before the Lord of Song / With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah” — Kate McKinnon gave a lot of us permission to have a good, long cry. —Rebecca Traister

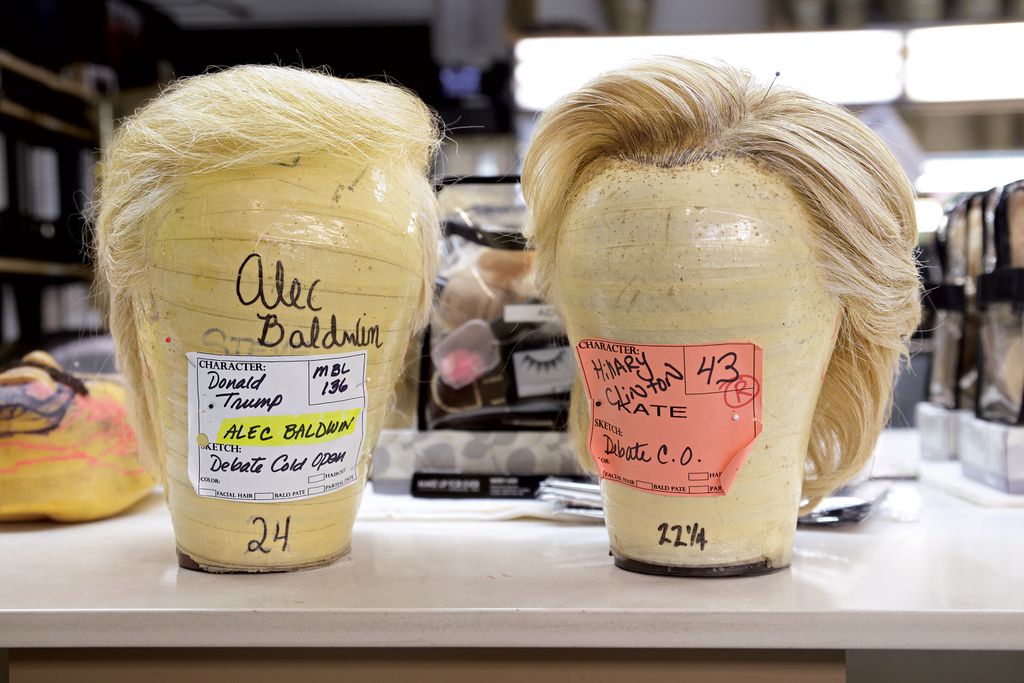

No. 10 | Because Alec Baldwin Is Just Trump Enough to Rile Trump.

No. 11 | Because Citi Bike HQ Has a Wall of Fame, With Many Leos.

Citi Bike’s private shrine to celebrities started in July 2013 — three months after the fledgling company set up shop in a warehouse in Sunset Park. The then–office manager saw a tabloid photograph of Johnny Galecki on a Citi Bike outside the Ed Sullivan Theater and printed it — he put the image in a frame from a dollar store and hung it on a bare wall across from the marketing department. From there, things expanded quickly. “We used to buy frames one at a time,” says Citi Bike director of communications Dani Simons. “But now we have to order them in bulk.” Some 60 images now hang on the wall. “People who ride consistently are up there multiple times,” says Simon. “There are three of Leonardo DiCaprio; Naomi Watts rides a lot. Karlie Kloss.” But mostly it’s one-offs: Bill Nye, the science guy; Lindsay Lohan; Woody Harrelson; Joe Jonas. “Quvenzhané Wallis is my favorite,” says Simons. “They used the bikes when they were filming the remake of Annie.” —Katy Schneider

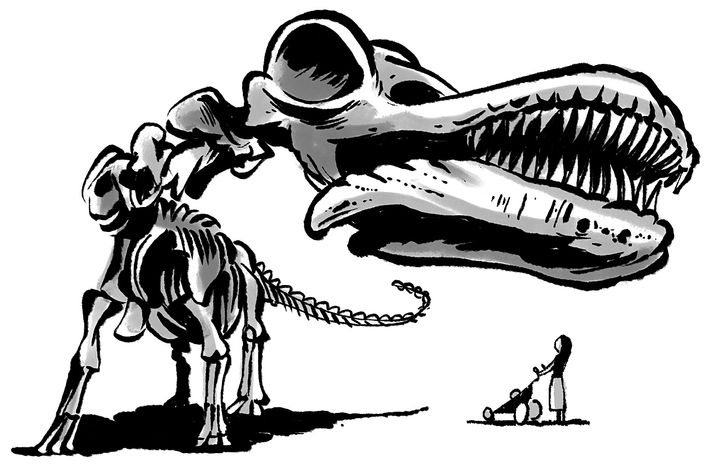

No. 12 | Because the World’s Biggest Dinosaur Skeleton Is Now at the Museum of Natural History.

Last January, a yet-to-be-named herbivorous Titanosaur was added to the American Museum of Natural History’s permanent collection, replacing a (comparably diminutive) Barosaurus that had been on display since 1996. The dinosaur — whose 70-ton skeleton consists of casts of 223 fossil bones excavated in Patagonia — is so large that its head couldn’t fit inside the orientation center’s gallery. “We were constrained by the size of the room,” says the museum’s chair of paleontology, Mark Norell. “We decided in the end to stick it out into the elevator banks — so when visitors walk into the hall from the stairs, it greets them.” After workers moved in the dinosaur, in pieces small enough to fit on the elevators and up the stairs, only one modification was left. “We had to make sure the head was high enough up that people wouldn’t try to jump up and hit it,” says Norell. —Katy Schneider

No. 13 | Because Saddam Hussein’s UES Torture Chamber Is Now a Kitchenette.

In October, the New York Post reported that the basement of 14 East 79th Street, a 1910 mansion that has served for 58 years as the Mission of Iraq, was used as a torture chamber under Saddam Hussein’s regime. The house was recently renovated, and the room converted into a functioning kitchenette. —Katy Schneider

No. 14 | Because the Prevailing Response to a Suitcase Bomb in Manhattan Was to Argue on Twitter About Just How Trendy, Exactly, Chelsea Is.

No. 15 | Because Of Course Our Free Public Wi-Fi Kiosks Were Immediately Used to Watch Porn.

It’s unclear how much porn was being watched on LinkNYC’s internet kiosks, the 500 or so converted pay phones that began turning up around the city last January, but it was enough to lead Councilman Corey Johnson to write a letter to the company to complain. LinkNYC responded by removing unfettered web-browser functionality. But that the kiosks led brief lives as public porn machines is touching, in a certain way — evidence that even an ever-richer, ever-cleaner New York is still resistant to the sanitized utopia of the tech industry. —Brian Feldman

No. 16 | Because the New York Liberty’s Dancers, the Timeless Torches, Are All 40-Plus.

Anybody is free to audition for the New York Liberty’s dance team. There’s just one catch: You must be at least 40. The current Timeless Torches lineup is made up of 13 members ranging in age from 40 to 76 and includes a legal assistant, an accountant, a Vietnam veteran, and an IT guy (yes, they take dancers of all genders). Margaret Hamilton, a 47-year-old legal secretary from the Bronx, joined at the urging of her daughter. “ ‘Mom! You are always dancing around,’ ” she remembers her daughter saying. “I said, ‘Well, I guess it’s like a free aerobics class.’ ” After her inaugural performance, “someone came up and said, ‘Can I have your autograph?’ I was so shocked that I forgot my name and signed ‘From Mommy.’ ” —Alexa Tsoulis-Reay

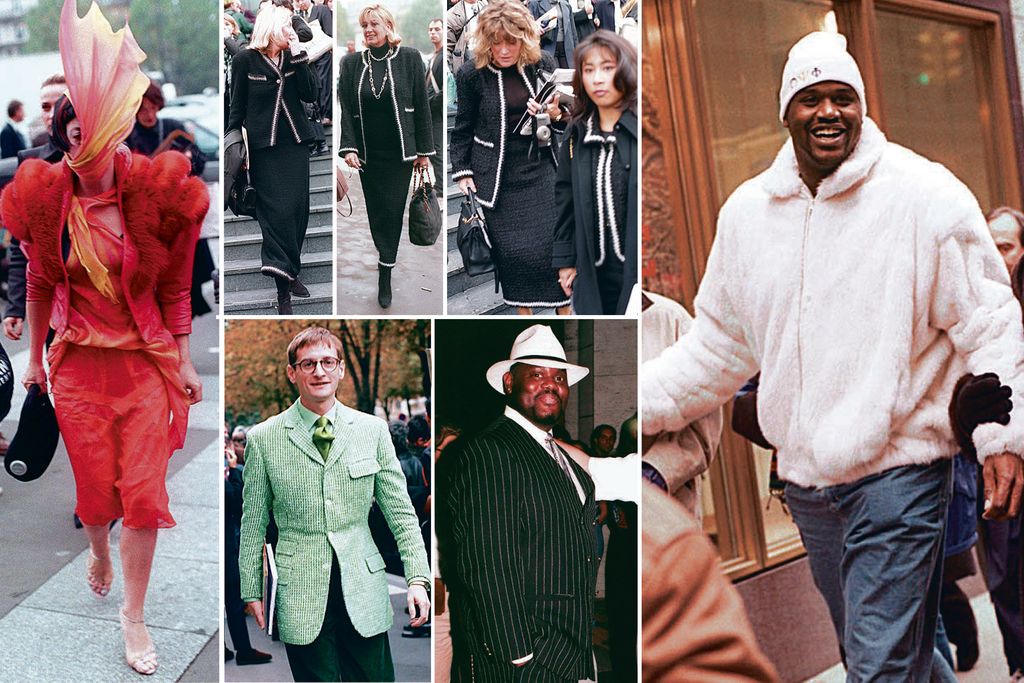

No. 17 | Because Bill Cunningham Saw It All.

And for 40 years, New York Times readers got to view the city’s clotheshorses through his eyes.

No. 18 | Because Dwarven Forge Is Brooklyn’s Manufacturing Base.

“One way to explain what I do,” says Stefan Pokorny, lord of the “Dwarven Forge,” “is that I build my dreams.” He sweeps a hand across his domain. Here, the majestic stalagmites of the Ice Caverns. There, the imposing stone walls of Narrow Passage. Looming over it all is the Royal Stronghold. It’s about four feet tall. “I’m like a Renaissance master,” says Pokorny, standing in his studio in Bushwick, dressed in a Rage Against the Machine T-shirt and baggy jeans. “I come up with the ideas and my apprentices help me execute them.” The part of the studio that’s not taken up with miniature fantasylands is full of PVC, modeling clay, and a small team of workers. “The other way to explain what I do,” continues Pokorny, “is that I make models for Dungeons & Dragons nerds.”

For the non-nerd: Dwarven Forge produces what amounts to Legos for role-playing games, selling a segment of castle wall, say, that customers buy and then assemble into larger “terrains,” the settings for the games. (The pieces are made from a proprietary material called Dwarvenite.)

Pokorny was an RPGer growing up in his family’s midtown-Manhattan brownstone. “I was always frustrated that the best gamers could do was draw the worlds that the games took place in. I wanted something physical.” So in 1996, in order to help support his floundering career as a painter of portraits and still lifes, he began making terrains and selling them to other gamers — the first to do so.

At the beginning, business was just okay, but his parents were happy to indulge their only child. “I wasn’t able to move into my own place until four years ago,” admits the 49-year-old Pokorny. Then in 2013, Dwarven Forge started its first Kickstarter campaign, raising $1.9 million. Now, it sells over $2 million in products per year. “We’re the Rolls-Royce of what we do” is how Pokorny explains his company’s success. Though, he admits, “Game of Thrones didn’t hurt either.” —David Marchese

No. 19 | Because a Guy in Staten Island Designed a Special Garbage Can for People to Toss Trash Into Without Stopping Their Cars.

“These fucking assholes can’t fucking help themselves,” says Scott LoBaido, the creator of the backboard-equipped repository, about the litterers who inspired his invention. “People were like, ‘Ah, Staten Island — just a buncha animals.’ I say, ‘It’s not just a Staten Island thing. There are animals everywhere.’ ”

No. 20 | Because Young M.A Makes Them Go Ooouuu.

“Once I let it out, I was like, man, I’m saying whatever now. You can’t tell me nothing now,” says Young M.A, the rapper from Brooklyn, as she grabs a chip and turns toward me on the white leather couch in the greenroom of The Wendy Williams Show, on which she’ll soon perform. “This is me,” she says. “I like girls, I got a strap-on.”

She wasn’t always this frank — she’s just finished telling me about coming out to her mom and her friends and how the fear of being outed clung to her until she turned 18. And then? “I just shaked it off,” she says, and here she tilts her shoulders back and does a sort-of stomach roll somewhere between Fat Joe’s “Lean Back” and Shakira’s belly dancing. It’s both a dance and sound bite that 110 million YouTube viewers will recognize from the last line of “Ooouuu,” which leaped to No. 5 on Billboard’s hip-hop charts after she independently released it this May on the strength of her rhymes alone (the song, unlike most hip-hop hits, doesn’t even have a hook).

Which brings us to an important distinction: An openly gay woman is, arguably, the most promising and original rapper recording music in the birthplace of hip-hop. And it’s not just that she’s openly gay — there have been queer rappers before — but that she is decidedly not femme. Young M.A is a masculine-presenting lesbian, pushing the black studs, AGs, bois, and butches into the spotlight of a genre that has historically been both misogynistic and homophobic. This has never happened before, and M.A has done it at a time when it’s been starting to feel like this city no longer has a distinguishable style. (“Panda,” the other hit song of the summer to originate in Brooklyn, relies heavily on Atlanta’s sound.) M.A calls her version “up top,” with “a bop to it” that’s reminiscent of the freewheeling fun (with a little violence) Bobby Shmurda brought back in 2014. “That’s Brooklyn,” she says. “New York is getting back to where it needs to be.”

In verse, M.A rarely gets introspective about her sexuality, instead running through all the typical rap tropes: the bro code, the partying, the girls who keep calling her, which, coupled with her low, raspy, androgynous voice, is why most people think she’s a guy when they first hear the song. Then they see her on YouTube and it’s “something fresh.” Which she is, standing up there on the Wendy Williams stage in her sagging Balmain jeans, limited-release OVO Jordans, and a Louis Vuitton scarf, with a hit song, making room for a whole new kind of mainstream hip-hop performer. The M. A stands for Me, Always. —Lauren Schwartzberg

No. 21 | Because the ACLU Is Ready to Rumble.

The morning after Trump was elected president, Anthony Romero, the executive director of the ACLU, made a defiant promise: “We’ll see him in court.” Bolstered by what Romero calls “the greatest outpouring of support” in the organization’s history — $19 million has flooded in since the election — the lawyers in the ACLU’s lower-Manhattan headquarters are preparing for a very busy four years. Romero expects immediate assaults on immigration, reproductive rights, and the First Amendment–guaranteed freedom to protest. “Those are the ones that we really have up on the whiteboard,” he says, “and we’re trying to figure out what we do if Trump crosses the Rubicon.”

During the Obama administration, conservative legal organizations mounted lawsuits that delayed or significantly altered the president’s initiatives, and Romero has reason to hope that a similar strategy will work for the ACLU. Despite the Supreme Court’s conservative tilt, it has given liberals important victories, such as the Bush-era ruling that upheld the civil rights of terrorism suspects imprisoned at Guantánamo. “Even with conservatives,” Romero says, “we can convince some of them when these issues get crystallized in the most fundamental way.”

Romero started his job at the ACLU the week before 9/11. “I am much more optimistic now,” he says. “Those were truly some of the darkest, most difficult days. There was very little debate. You have a very different environment now. You have a media that is paying very close attention to these issues, you have a public that is vigorously engaged, taking to the streets, and you have formidable institutions that will use every strategy, whether legislative or in the courts or organizing, to forestall the worst damage.” As Trump proved, fear is a powerful mobilizing force. —Andrew Rice

No. 22 | Because since Trump’s election, New Yorkers have given 33,800 gifts to the ACLU, totaling $2.5 million and 180,000 people bought New York Times subscriptions, ten times its normal rate.

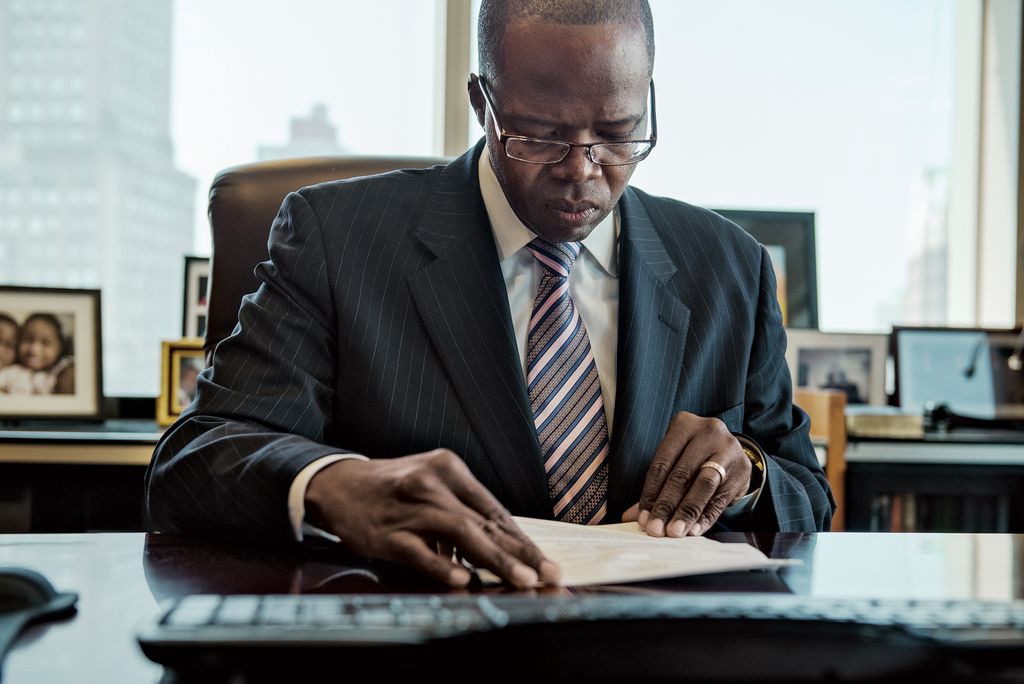

No. 23 | Because Ken Thompson Fought to the Very End.

Ken Thompson, Brooklyn’s first black district attorney, came in as a reformer. Within months of his election in 2014, he announced that his office would refuse to prosecute low-level marijuana possession and set up a kind of Innocence Project inside the DA’s office, which reconsidered hundreds of claims of wrongful imprisonment and vacated 21 convictions.

Both initiatives had been popular enough that he’d started privately talking about running for mayor. But then Thompson began cutting back his hours and going out of his way to spend more time with his wife and kids. When, in April, Thompson called Wayne Williams, his deputy chief of staff, into his office, the aide thought he was going to say he wouldn’t seek reelection. “I thought Ken was giving up,” Williams says.

Instead, Thompson said he had been diagnosed with cancer. It began in his colon and spread fast. By September, he was too sick to go into the office. From his home in Clinton Hill, and later his hospital bed at Sloan Kettering, he continued to push his prosecutors in their investigation of a gang shoot-out that resulted in the accidental death of Carey Gabay, a Cuomo-administration lawyer. Gabay, like Thompson, grew up in a Bronx housing project. “Ken saw a lot of himself in Carey,” Williams says. Thompson stayed involved, too, in the investigation into the murder of Chanel Petro-Nixon, a teenager whose body was found in a garbage bag in 2006. In June, when detectives turned up new evidence that led to an indictment, Thompson called a press conference to announce the news. “I don’t know how he held up,” Williams says. “He’d just gotten his treatment. The day was hot, and he was in his suit, trying to not show anyone he was sick.”

Thompson publicly announced his diagnosis in October. “As a man of intense faith, I intend to win the battle against this disease,” he said. He died five days later. In his final months, he worried about his legacy. “He feared that all of his work could be erased,” Williams says, and believed the solution to keeping his progressive agenda intact was to recruit more prosecutors like him who understood New York from the ground up. “I’m not going to toot my own horn, but for me to sit here and talk with you as Brooklyn DA, based on where I come from,” he told me soon after taking office, “I’d take you right to the building I started out in, and you’d see those kids running around. That was me.” —Geoffrey Gray

No. 24 | Because New York Would Never Dream of Building a Wall.

“Sanctuary city” is a phrase that gets tossed around increasingly, but it has no specific legal meaning. It refers to cities that have adopted — some in response to federal laws that compel municipalities to report undocumented immigrants — an unofficial (or, in some cases, quasi-official) policy of noncompliance. The tally of such cities is inexact, but this year the Immigrant Legal Resource Center identified 38 of them in the U.S., including, of course, New York. That ours is a sanctuary city — arguably, the sanctuary city — shouldn’t be surprising. After all, for 130 years we’ve displayed, in the New York Harbor, the most iconic symbol of welcome in the world. In the weeks after an election season defined in part by an ugly debate over who should be allowed to live here, New York photographed dozens of immigrants and new citizens, ranging in age from 1 month to 91 years, to suggest the breadth of the New York–immigrant experience. Of course, capturing the full breadth would be impossible — there are 3 million New Yorkers who were born somewhere else, more than a third of the city’s population. (To read and watch more about their stories, go to nymag.com.) All of which is a good reminder that even the city’s hoariest come-hithers — make it here, make it anywhere, etc. — contain an implicit promise: Our city is open to anyone who’s willing to give it a shot. Give us your poor, your tired, your huddled masses, yes, but also your ambitious, your artsy, your queer, your shunned, your misfits, and anyone else who can’t, for some reason, feel at home where they are. Whatever it is you’re a refugee from, this city can be your refuge. We may have a fabled reputation for crossed-arm toughness, but in reality, New York is the city whose arms have always been open the widest. —Adam Sternbergh

No. 25 | Because the Universally Acknowledged Dump That Is La Guardia Airport Is Finally Getting an Upgrade.

When it comes to departure delays, Chicago’s O’Hare International, where 27.5 percent of flights leave late, is actually slightly worse. (La Guardia is at 27.25 percent.) That ranking does not, however, incorporate baggage handling, comfort of security operations, quality of Wi-Fi, or general busted-down-ness, because if it did, La Guardia would be unbeatable. It is a barely functional, emotionally exhausting place to begin or end a trip. And it’s very ugly. It’s so bad, in fact, that people who never agree on anything can agree on this. “Like from a Third World country,” our next president has called it, ungrammatically but not incorrectly. Joe Biden used similar language in a 2014 speech. “Outdated and poorly designed,” said Andrew Cuomo. Mike Pence hasn’t slagged it publicly, but he must’ve had a moment of clarity when his jet skidded off the runway at La Guardia in October.

Last year, Cuomo unveiled a plan to rip it all down to the tarmac level and start anew, keeping only Marine Air Terminal. In June, a public-private consortium called La Guardia Gateway Partners signed a 35-year lease with the Port Authority to rebuild and operate the reimagined airport, which replaces a lot of discrete buildings with one unified and interconnected structure. Even if we don’t get quite the flight experience we deserve — the runways, after all, are not going to get any longer — we will likely end up with the best airport that can be shoehorned into that space. The Gateway Partners deal does not depend on the infrastructure spending that Trump has promised us, and the bonds to pay for it have already been issued. Amazingly, the governor’s office says that some gates will open for business in 2018. If it comes out as well as the renderings look, count on President Trump to try to get his name on it somehow. —Christopher Bonanos

No. 26 | Because the Lettered Lines Are Getting Countdown Clocks.

No. 27 | Because not only is the Second Avenue subway finally, actually here (or at least four stations of it), but the next generation of subway cars will soon arrive, most featuring open gangways so passengers can safely move between cars; Wi-Fi, so every train delay can be properly tweeted; and USB ports, so if you happen to be near a port, with a cable, indifferent to the prospect of surreptitious data collection, and able to delicately reach over the guy who’s plugged in before you and fallen asleep against the panel, you’ll be able to charge your phone.

No. 28 | Because This Meat-and-Potatoes City Is Now a Vegetarian Paradise.

I can remember precisely where I was when it dawned on me, with a kind of stunned clarity, that the culinary fashions of this traditionalist, meat-and-potatoes city had turned, more or less on a dime. I was standing by the perpetually mobbed counter of a popular new vegan establishment in the West Village called By Chloe, waiting for my surprisingly edible tempeh-lentil-chai-walnut vegetable burger to arrive, when a solidly built gentleman shuffled forward in the line. He had the girth of a seasoned steakhouse carnivore, and unlike the majority of the skinny crowd arrayed at the jammed communal tables, nibbling on mounds of kale Caesar and various other tempeh-based products, he wore a dark Wall Street suit and a silk tie. “What the hell are you doing here?” I asked as we furtively examined the rows of cleansing fruit juices and chia puddings arrayed in the display case. The gentleman looked me up and down. “What the hell are you doing here?” he replied.

All around this desperately fashion-conscious town, discerning gourmets who once closed their eyes in fits of ecstatic pleasure while tasting that perfectly seared lobe of foie gras now affect the same expressions of faux rapture while tasting bowls of well-turned turnip soup cooked in the Japanese Buddhist style. There may be purer examples of avocado toast available out in L.A., but nowhere will you find more varieties of this trendy dish than in the endlessly proliferating veggie-conscious dining counters of New York City. And you won’t taste vegetable versions of beef Wellington like the one the talented chef John Fraser makes with carrots at his downtown restaurant Narcissa instead of beef. The great pied piper of the gourmet-veggie era, Dan Barber, fashioned his famous “Wasted Burger” from the contents of restaurant trash cans. If you’re searching for a slightly less sinful substitute for your weekly Shack Burger, however, you’ll find it at former pastry chef Brooks Headley’s excellent Superiority Burger in the East Village, or, my stolid beefeater friend and I heartily agree, at any of the locations of the rapidly expanding By Chloe empire, which just opened an outlet in Silver Lake, of course. —Adam Platt

No. 29 | Because the NYU Maternity Ward Serves Bone Broth.

A cart is rolled out daily to serve cups of the nutrient-rich, on-trend soup from Brodo, the takeout extension of chef Marco Canora’s Hearth.

No. 30 | Because the Park Slope Food Co-op Has No Truck with “New McCarthyism.”

A couple of weeks after the election, the Park Slope Food Co-op’s in-house newspaper, the Linewaiters’ Gazette (around since 1973) published “What Trump’s America Means for the Coop,” which covered Trump’s potential effects on the availability of food stamps, immigrant farm labor … plus how members broke the news to their kids. As a selection of the paper’s headlines from the past year makes clear, liberals will always have the co-op, if not the White House. —Chadwick Matlin

“An Election Squad to Ensure Coop Democracy” (Mar. 17)

“Omnivore Oppression?” (Mar. 31)

“Judged Extremely Uncooperative, Four Members Suspended for One Year” (May 12)

“Plastic As Food Poisoning” (May 26)

“The New Meeting Room Policy Is Unwarranted Infringment on Freedom of Speech and Freedom of Assembly” (Jun. 23)

“The ‘New McCarthyism’ in New York State and at the Coop” (Jun. 23)

“On Behalf of the Canines” (Jun. 23)

“Could the Power of Performance Bring Peace to Coop Shopping?” (Jul. 21)

No. 31 | Because the Internet Is Under This Manhole.

In 2013, when Edward Snowden revealed that the U.S. government was collecting troves of data on its citizens, the artist and writer Ingrid Burrington was struck by how news accounts illustrated the internet: stock images “of a guy in a hoodie, or a screen with a lock made out of ones and zeros,” she says. “I kept thinking, I don’t know what the internet looks like, but I don’t think it looks like this.” Burrington decided to figure out what the internet does look like, at least in New York. “Some of it,” she says, “was just going up to people working in open manholes and asking them ‘Whatcha doing? What’s this?’ ” The result was a self-published book called Networks of New York, which this year was updated and republished by Melville House. An “illustrated field guide to urban internet infrastructure,” it’s a slim, pocket-size volume that an amateur cable-spotter can use to decode the city’s secret telecommunications infrastructure — the anonymous gray or green junction boxes; the orange symbols spray-painted on the pavement noting the locations and owners of underground telecom cables; or the “carrier hotels,” like 111 Eighth Avenue, at Google’s local offices, where hundreds of networks connect to one another, transporting stock-market trades, account transfers, and emails, and streaming songs in an impressive feat of engineering and commercial negotiation. —Max Read

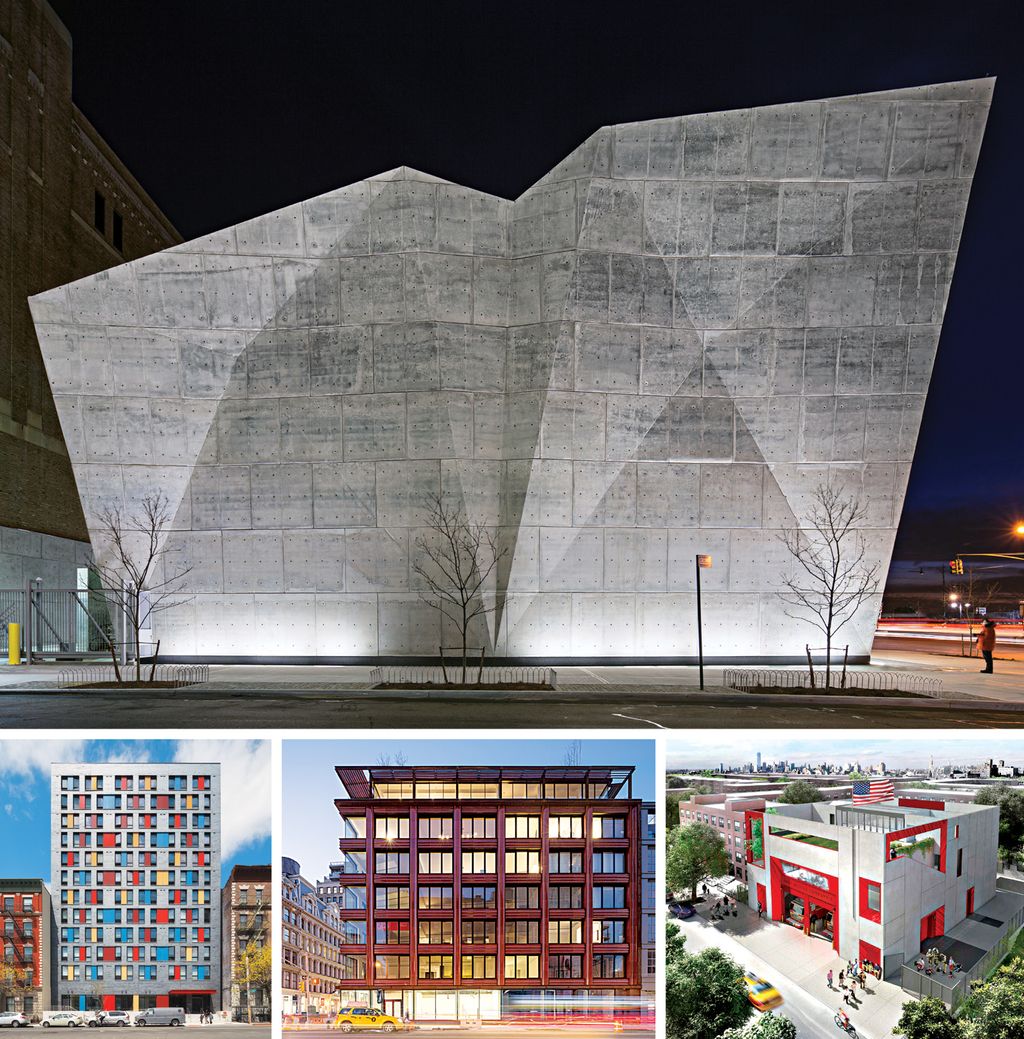

No. 32 | And Because Our Snow-Salt Sheds Look Like Museums.

The city is awash with megaprojects, quarter-mile-high towers colonizing the sky above Manhattan, and new transit tunnels Swiss-cheesing the ground below. Some of the finest recently built and in-progress architecture, though, operates at a more modest scale. —Justin Davidson

Spring Street Salt Shed (Soho)

Instead of plopping down a big utilitarian box and pretending nobody could see it, Dattner Architects and WXY designed a concrete crystal that is both delicate and tough, with cool, fractal elegance.

Boston Road (Allerton)

Alexander Gorlin’s frugal but vivid South Bronx housing for the formerly homeless makes the most of its constraints, enlivening charcoal brick with colored metal and fitting out the lobby ceiling with wavy strips that suggest the flank of a rocky gorge.

10 Bond Street (Noho)

Annabelle Selldorf, a virtuoso of glazed terra-cotta, uses it here to fashion a grid of heavy, luxuriant frames, as if residents were figures in a domestic genre scene.

Brooklyn Firehouse (Brownsville)

Studio Gang is building the FDNY a concrete firehouse trimmed in flame-red glazed terra-cotta, an eloquent combination of muscularity and engine-company gleam. It’s more than just a pretty façade, though: Voids, porches, and balconies allow air to flow through the building and let firefighters practice a range of rescue scenarios.

529 Broadway (Soho, here)

For this six-story mega-Niketown, BKSK Architects wrapped a glass shell in lacy tiles. Beneath the bulky cornice, the façade seems to swirl, getting denser on Spring Street and more see-through on Broadway.

No. 33 | Because Our Governor Believes in the Morning Martini.

Until last summer, an early Sunday brunch was a boozeless affair. That changed after Governor Andrew Cuomo updated the state’s post-Prohibition liquor laws, declaring the ban on cocktail sales before noon on the day of rest “the most bizarre, arcane, frustrating, maddening law that you could imagine.” Now New Yorkers can drink cocktails at restaurants as early as 10 a.m. — in some instances 8 a.m. — even on the Lord’s day. —Chris Crowley

No. 34 | Because the City Is Spending $11 Million on Amateur Hour.

Since 1973, when it was founded in a living room, the Nuyorican Poets Cafe has maintained its freewheeling rec-room vibe, while helping to launch Alvin Ailey, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Junot Díaz, and Paul Beatty, who was awarded his first book deal for winning a 1990 poetry slam and this year won the Man Booker Prize. Now Nuyo has cobbled together $10.9 million from city grants for a massive expansion. Its performance space will grow from 1,533 square feet to more than 7,000, allowing the annual slate of 545 events to increase to 1,300. It’s also adding recording and live-broadcasting capabilities, a residency program, and a more-robust theater-development program, things that were pipe dreams a few years ago. “Success is often described as turning art into numbers,” says Daniel Gallant, Nuyo’s director, “but the reverse of turning numbers into art is its own craft.” —Richard Morgan

No. 35 | Because Justin Trudeau Got Punched in the Face Here.

Last April, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau was in town to sign the Paris Agreement on climate change and stopped into Gleason’s boxing gym in Dumbo for some exercise. “He was keeping his hands a little low,” recalls Yuri Foreman, the former super-welterweight world champion who sparred with him. “The first time you do that at Gleason’s, we say, ‘Don’t keep your hands low.’ ” The PM dropped his hands again and learned what happens at Gleason’s when you do that a second time. “I hit him in the face,” says Foreman. Trudeau, Canadian to the core, took the lesson graciously. “He said, ‘If I don’t get hit, it means I’m not learning.’ I had to correct him and tell him that in boxing, if you’re getting hit, it’s not good.” —David Marchese

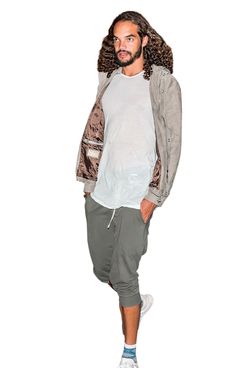

No. 36 | Because The Knicks’ Center Learned to Play at P.S. 149.

Despite Carmelo Anthony’s personal rebranding efforts, he’s never quite been accepted as a New Yorker by the Knicks faithful. And while Joakim Noah is nowhere near the player Anthony is, his move to the Knicks from the Chicago Bulls has given fans that rarest of things: a hometowner to believe in. Born here in 1985 to a French-Cameroonian tennis-star father and Swedish artist mother, Noah grew up playing pickup games at P.S. 149 in Queens and eating slices of pizza from Kennedy Fried Chicken while riding the train back home to Hell’s Kitchen. Patrick Ewing even gave him his first basketball. Part of Noah’s charm is that for all the ways he stands out — six-foot-eleven, with a questionable man-bun, an awkward stride, and a screwball jump shot — he also fits in, in a perfectly New York way. “He’d be hanging out with his friends in the Village one day, then up at the 92nd Street Y the next day,” says his old Poly Prep coach Bill McNally. “And he was here for 9/11, and that made him feel even more strongly about New York.” So forget that he’s been struggling this season; he’s still one of ours. —David Marchese

No. 37 | Because the No. 2 College-Football Recruit in the Country Is From Canarsie and Wears a SpongeBob Backpack.

By age 10, Isaiah Wilson was five-foot-six, and thick. “I looked at his shoulders and said, ‘He looks like a little linebacker,’ ” says his mother, Sharese Wilson. The parents of other children saw the same thing, and, worried about the damage he might do to their kids, forced Wilson to play in a flag-football league until he lost enough weight, and his classmates gained enough, that everyone felt relatively safe giving him pads and a helmet and letting him hit people.

Wilson is now a six-foot-seven, 354-pound senior at leafy Poly Prep, in Dyker Heights — a 45-minute bus ride away from his Canarsie home — and ESPN’s No. 2–ranked high-school football player in the country. New York City has produced plenty of point guards and power forwards over the years, but top football prospects from the five boroughs are a rarity. “Come take a look at this,” Kevin Fountaine, Poly’s head coach, says, sitting at his desk, which is decorated with letters from college coaches thirsting after his star player. Poly has only 40 players on its roster, and none with Wilson’s size and ability, so he is called on to play a variety of positions on both offense and defense, including quarterback. Fountaine grins as he pulls up a clip from a recent game in which Wilson lined up in the shotgun at the five-yard line, took the snap, ran left, shoved an opposing defender to the ground with one arm, barreled through another with his shoulder, then dragged four more into the end zone. “He’s just a freak,” Fountaine says.

Despite his size, Wilson, who wears a SpongeBob backpack, has a quiet demeanor and the floppy handshake of a mathlete. During a recent team film session to break down game tape, he sat front and center, blocking the view of more-high-school-size teammates behind him (among them a five-eleven, 165-pound freshman outside linebacker who is Jon Bon Jovi’s son). The team watched as Wilson body-slammed an opponent to the ground, then burst through a triple-team. Wilson weighs nearly a hundred pounds more than his next-largest teammate, and most of the roster bears less resemblance to an SEC football team than it does to my high-school team (I played tennis).

Wilson spent the past month on visits to Alabama, Georgia, Florida State, and Michigan, but he has yet to decide where he will go and prefers to keep coaches and fans, who scrutinize his every tweet, in the dark. After the film session, and before the team went to the weight room, Wilson changed out of an Alabama shirt and sweats and into a similarly matching outfit from the University of Georgia. Wilson says he doesn’t want to rush his decision, and that wherever he goes, he isn’t worried about being pushed around. “I don’t want to come off cocky or anything, but I am confident in my abilities,” he says. “I know what I can do.” —Reeves Wiedeman

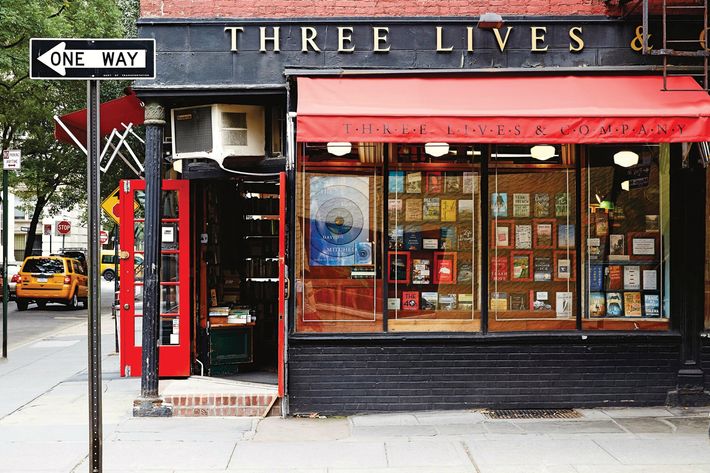

No. 38 | Because Three Lives & Company Found a Fourth Life.

In September, the building at West 10th Street and Waverly Place was sold to a firm called Oliver’s Realty Group, and you’d be forgiven for expecting a familiar grim story about the closure of a favorite shop to have played out thereafter. The building’s retail tenant is Three Lives & Company, a bookstore of the oldest type: hand-selling, hand-recommending, beloved by its regulars, even more beloved by those writers who can still afford to live nearby. There was not a lot of hope that this time would be different. Yet Three Lives — founded in 1978, and in this location since ’83 — was able to announce last month that it will stay put indefinitely, under conditions that both landlord and tenant confirm are sustainable for the long term.

The economics of bookselling are still tough. It takes not only a benevolent landlord but cleverness and long hours to keep a bookstore in business. (Just last week, the owners of BookCourt, in Cobble Hill, announced that they’re going to retire and close down; the author Emma Straub, who clerked there, says she’s going to start a new store to pick up where they left off.) In the Village, rents are high, and it’s a hard climate for non-luxury-goods retailers. The margin on $25 books cannot compete with that of $1,000 Marc Jacobs sweaters. Paradoxically, though, Amazon — by causing Barnes & Noble to close a lot of locations and Borders Books to shut down altogether — has had a weird pro-indie effect. Those that have managed to survive, like Three Lives, can reclaim freed-up slivers of market space where they can exist, and maybe even flourish. —Christopher Bonanos

No. 39 | And Because These New York Institutions Are on at Least Their Second.

Gone doesn’t always mean forever. Some New York establishments, once taken for dead, have sprung back to life this year. —Richard Morgan

Hudson Theatre: The 44th Street theater was built in 1903 and housed the first national broadcast of The Tonight Show in 1954. It closed in 1963, switching to porn. Now it’s Broadway’s 41st theater, the first new one since 2010.

Chumley’s: Just 3,483 days after a chimney collapse in April 2007 suddenly wiped it off the map, a dramatically upscale reincarnation of the legendary 94-year-old onetime speakeasy opened in October.

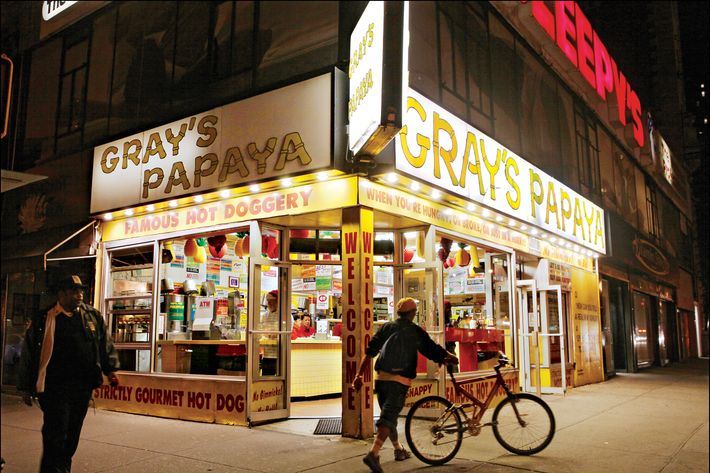

Gray’s Papaya: The revered local 24-hour hot-dog chain famed for its Recession Special had dwindled to one last outpost, on 72nd Street. But now a new location is opening near Port Authority.

Pearl River Mart: When the 30,000-square-foot Soho market for deliriously weird Asian bric-a-brac closed in March after 45 years downtown, it seemed a bygone relic of old New York. But then it reopened in November in Tribeca.

No. 40 | Because Stephen Powers Understands the Mythic Importance of Old Signs.

Brooklyn’s past is often mined for faux-old-timey nostalgia that never really existed, but artist Stephen Powers manages to do the opposite: revive the Coney Island street-signage patois of a city that once was as a way to say something new. Innocent at first, its aphoristic weight sneaks up on you.

No. 41 | Because the Homeless’s Best Advocate Wrote His Way Out of the Shelter System.

After his job was eliminated and his severance ran out, then his 401(k), Rob Robinson ended up on the streets of Miami. In 2005, after two years there, he got a bus ticket to New York. His plan was to be near his family, but when he arrived at the Port Authority and looked at his unkempt reflection in the mirror, he couldn’t bring himself to call his sister. So he checked into a shelter. But just because you’re homeless doesn’t mean you’re not who you were before. Robinson had been a project manager for a payroll company, and soon he began trying to manage the shelter. “I started pestering,” he says. He brought his ideas for improving food quality, access to the showers, and overall cleanliness to his caseworker. “The shower thing was particularly disturbing. Folks would get into fights about who was in line first.” When nothing changed, he wrote letters to the facility’s director. That led Robinson to a spot on the New York City Coalition on the Continuum of Care, which monitors how $110 million goes into housing the homeless. It also led him out of homelessness: Now he has an apartment and part-time work with nonprofits, and gives talks all over the world. “I’ve been able to articulate going through homelessness,” he says. “It challenges the solutions that government came up with.” —D. W. Gibson

No. 42 | Because the New Brooklyn Food Craze Is Headstone to Table.

In 2015, Davin Larson bought six hives of about 100,000 bees and moved them into Green-Wood Cemetery between Jean-Michel Basquiat and Leonard Bernstein. The lucky bees started snacking on anything they could find, and in October Larson harvested about 200 pounds of honey in flavors from mint to tangerine — thanks to the cemetery’s diverse flora. —Lauren Schwartzberg

No. 43 | Because a Columbia Lab Is Trying to Turn Corpses Into Glowing Installation Art Under the Manhattan Bridge.

Around 15 years ago, while Karla Rothstein was teaching graduate architecture students at Columbia and focusing on the city’s peripheral spaces, she took an interest in cemeteries. The city’s total cemetery space equals roughly five Central Parks, but inevitably, just as land for the living has become unattainably dear, so has that for the dead. More than 50,000 people die in New York every year, but two-thirds of those who choose earthen burial are now interred outside the five boroughs. “That’s a lot of memory, a lot of honor, a lot of perspective that we’re sending out of the city,” Rothstein says. It’s also environmentally harmful, creating distances that bodies must be shipped and relatives must travel, and leaching formaldehyde into the ground.

And so, seven years ago, Rothstein launched DeathLab, with partners who now include a theologian and a MacArthur-grant-winning expert on microbial communities, to rethink cemeteries. They looked at the pros and cons of cremation: Though it reduces a corpse to 4 percent of its mass, helpful for space-efficient stacking, the incineration of a corpse uses as much energy as a living person does in a month at home. Natural burial — putting an unembalmed corpse in a shroud or a biodegradable coffin made of wicker or cornstarch — is easier on the Earth but doesn’t solve the land-scarcity issue. And it has the same carbon-footprint problem as unnatural (embalmed) burial, because of body transport and relatives who drive their gas-guzzlers to visit the graves. Chemical cremation (known in the industry as “flushing Grandma down the drain”), already legal in a dozen or so states, is marketed to use less energy than its fiery namesake but is controversial because it leaves a lot of liquid to be disposed of.

What began as a methodical winnowing process led DeathLab to something new and sublime. For the past few years, DeathLab has been focused on what it calls Constellation Park: a twinkling vault of glowing pods suspended under the Manhattan Bridge. (The city hasn’t said yes yet, but some City Council members are onboard.) The idea is to use “anaerobic bioconversion,” accelerating decomposition of corpses in airless chambers and harnessing the gas released to power memorial lights. The idea captures both the intimate and the collective aspects of death, with each corpse in its own pod but all of them together forming a luminous array of shifting intensities. Part of the agenda is to change our relationship with death, to reintegrate it in communities instead of having it be cut off from us in distant, unseen places.

Rothstein hopes to have an operational prototype pod in two years. “The typical arc of a conversation — on the subway, at a funeral, at a grocery store, at a dinner table — is, someone will bring up what I’m working on, and someone across from me will say something along the lines of, ‘Good luck with that.’ And then, within ten minutes of dialogue — about the process relative to the world we’re in today, relative to the city we’re in, relative to other options — most people are ready to sign on.” —Benjamin Wallace

No. 44 | Because Fashion Cares For Its Own.

In what we did not know would be the last year of his life, my brother Mark got model-scouted on the subway. He was chased down by a man who hopped into Mark’s subway car, handed him a business card, and jumped back out before the doors closed. Mark assumed it was a scam. The next day, the same man tapped him on the shoulder in the New School cafeteria. It was Tsuyoshi Nimura, N.Hoolywood’s casting director.

He walked in N.Hoolywood’s show that January. By then, we were used to watching him for subtle clues and begging him to try something, anything, to get better. Maybe this new career, or lark, would help. Mark had really begun to struggle in middle school. By the time he admitted he was suicidal, at 14, he’d been depressed for years. He left the city — for a psych ward upstate, a wilderness program in Oregon he simply called Woods, a residential school in Utah. But soon after he came back for good, Mark’s friends went off to college, and he did not.

The summer following his turn on the runway was rocky, and in the midst of it, N.Hoolywood asked him to walk again. The show was on my birthday, and I refreshed my phone through dinner with friends, thrilled when his photo hit the internet. Soon after, Mark decided that he wanted to get out of the city and see some other places. Asia, he decided, and maybe he would even go to Japan and visit the N.Hoolywood team. They’d given him their cards, he’d said. I didn’t mention that they probably didn’t expect him to show up in Toyko. Mark did his research, got his travel shots, but then delayed his departure. Instead of getting on a plane, he went back to his therapist, said he felt that everyone was moving on and he didn’t know how to go forward. Thanksgiving came and, with it, all of his friends. He had a whole bunch of them over to drink beer and catch up. I wonder if he knew then it was good-bye.

A few days after that Thanksgiving break, in early December, Mark, 21 years old, committed suicide at home, family members nearby but not close enough.

I was living in Berlin by then, and when I came home all his travel things were scattered around his room in stacks, awaiting the trip he never took. I began to pore over photographs. There he was, tiny and drooling; dressed as Elvis for Halloween when all his friends went as action figures; in one of the vintage sweaters he’d proudly picked out with his girlfriend. That’s when I remembered the look book he’d handed me with a sheepish smile. He was living with me in Brooklyn the summer before I went to Berlin, and one afternoon he came out to the living room with the thick-card-stock booklet. I’d said I’d be his manager, after all.

But I couldn’t find the book. I sent a plea to the Japanese fashion house, explaining the circumstances and begging for a few copies. A few weeks later, a big envelope filled with look books came back from Japan, and so did a request: Tsuyoshi Nimura, Mark’s casting director, will be in New York for Fashion Week. He would love to visit Mark’s grave or meet you if possible.

When someone you love dies, you want the whole world to stop, which it never does. But in Nimura, a near stranger, I felt the depth of my loss reflected back. He arrived and almost immediately burst into tears. Nimura mentioned Mark’s contagious smile and his sweetness. We laughed about Mark’s love of flip-flops and his fear, after the first show, that he’d been shaking so much the cameras couldn’t have gotten a clear shot. (They did.) “He had a beautiful silhouette,” Nimura said, “and so I had no choice but to chase him.”

N.Hoolywood invited my whole family to go to the show two weeks later. For us, the show was not about cold-weather trends, but the boy who’d never again wear a winter coat. After the final models, Nimura came out to bow alongside the designer Daisuke Obana, and on the stomach of his sweater, on a piece of duct tape, Nimura had written WE <3 MARK. On his back was another piece of duct tape: DO OUR BEST FOR MARK. —Alex Ronan

No. 45 | Because This Cabstand Still Serves the City’s Best Chai, Even After the Cabbies Went Away.

This time, I came back to New York and thought: It couldn’t possibly still be there. Soho, where my favorite Pakistani deli, Lahore, is located, has been menacing the little guy for at least 30 years. The second-to-last gas station in lower Manhattan, across from the deli, had been its lifeblood, supplying it with famished cabbie customers. It had been demolished earlier that year. But Lahore — Lahore was still there! (In my memory, I had elevated it to the second floor; actually, it was on the first.) I went in before a reading at Housing Works, next door, and sipped a splendid $1.50 chai: overly heated, numbing the tongue to criticism; spiced but not ostentatiously so. I had guiltily said “yes” when the cashier asked if I’d like sugar in it. And because the classic swirly-patterned deli cup came without a cardboard cozy, I ended up clutching it the way people clutch chai glasses in India: with two fingers pincered around the mouth. I became, I hope, the most fragrant person at the literary gathering.

I went back again and again in the weeks to come — it was a counterpoint to the enervating experience of shopping in Soho, turnstiled by crowds. The concrete shelves were crazily heaped with buns and medicines and paper towels and mixed pickles; the insouciantly bearded fellow behind the counter said “As-salaam alaikum” to customers and always teased me about the cost (“$15 for the chai and food,” he said, and was astonished when I believed him); there were alert, alien-white people lining up alongside the Sikh and Hindu and Muslim taxi drivers from Asia in their mufflers and sweaters. I dripped chai onto a new Brooks Brothers shirt, still in its stiff blue bag; I splashed it happily on my winter jacket as I hurried down into the subway; I dumped a searing cup into the trash at the New Museum. But I was happy to have a connection to home.

An Indian, I had found my own private Pakistan in New York. —Karan Mahajan

No. 46 | Because a Bodega in the Lower East Side Will Deliver You Plan B Via Seamless, Alongside Your Bacon-Egg-and-Cheese.

No. 47 | Because Hillary Clinton Thought Brooklyn Could Be the Capital of America.

She went to Roberta’s once, and I hear she’s been seen at Cipriani lately, and it is a known fact that she has shopped with Anna Wintour, but the truth is that Hillary Clinton moved to New York for work (like so many others here). They called it “carpetbagging” at the time, an opportunistic grab at a Senate seat, but the gambit wouldn’t have worked if Hillary and New York hadn’t been a good fit, hadn’t recognized the best of themselves in each other. Sure, in retrospect, to be an untested freshman senator from her home state of Illinois might have been a better path to the presidency, but Clinton was deeply ambitious — is now, and ever shall be, even if she’s lost in the wilderness of Westchester wearing a fleece she’s had since 1995. “Chicago’s great and all, a world-class city,” as Michael Tomasky wrote in this magazine in 1999. “But who’s she going to hobnob with in Chicago, that lady who writes the V. I. Warshawski novels?”

Meanwhile, it wasn’t just her famous last name, or her unceasing drive, that recommended Clinton to this town. It was her brand of liberalism: in equal measures practical about the way the world works (yeah, so she let some bankers pick up the tab; so have a lot of us!) and utopian about making it better (lost in the Year of Bernie was the fact that Clinton would have reshaped the economy in a deep and radical way, particularly for women and families). When she moved her presidential-campaign headquarters to Brooklyn Heights, it was a gift to the Twitter wags who made jokes about hipsters, never mind that the staid neighborhood she picked was just about the least hip part of the borough (home to the courthouse, an Ann Taylor Loft, and such artisanal hot spots as Hale and Hearty). But it was also a declaration that her adopted city, and this even more newly adopted borough, was in its progressive idealism, and despite all its easily pilloried tropes, the spiritual home of her politics. For a while, it seemed it could be the spiritual home of American politics, too.

That was the great thing about this campaign. She went for it this time: Remember the unmitigated defense of abortion rights she gave in the third debate? Her unapologetic identification as a feminist? Even her ongoing dialogue with Black Lives Matter felt like it was, authentically, Hillary: a transplant who better represented New York than a native. —Noreen Malone

*This article appears in the December 12, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.