The nomination of Neil Gorsuch for the Supreme Court has divided and confused the Democratic Party. Democrats have no common agreement on a strategy, or even what objective to pursue. Thus they find themselves divided between one faction pursuing hopeless, doomed confrontation, and another advocating capitulation. The correct strategy is to approach the nomination from the standpoint of maximizing their ability to win future Supreme Court nomination fights. That means mounting a filibuster against the nomination, forcing the Republican Party to end the filibuster, and then voting to seat Gorsuch.

The liberal argument for refusing to filibuster the nomination proceeds from the assumption that Democrats have the choice between Gorsuch and some other justice, and should base their vote on his qualifications and record. Gorsuch comes from “the far extreme right,” says Senator Jeff Merkley, who is leading the opposition. On the opposing side, Gorsuch’s Democratic defenders insists he is better than the alternative. “Moderates could do a lot worse than Judge Neil Gorsuch,” argues Yale law professor E. Donald Elliott, “and we probably will if he isn’t confirmed.”

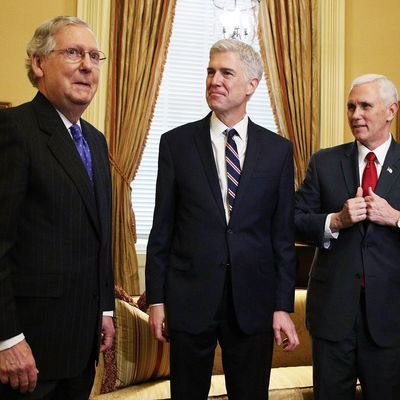

The prospect that Gorsuch will be defeated and replaced with a more extreme alternative is not worth considering. His nomination is a fait accompli. Republican Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced last month that the 52 Republican senators would seat whomever Donald Trump nominated for the Supreme Court vacancy — “The nominee will be confirmed” — even if it required abolishing the filibuster on Supreme Court nominations. Defeating Gorsuch is not a realistic option for Democrats.

Contrary to the slogans of Gorsuch’s critics, he is not extreme by the standards of a Republican nominee. The reason to oppose him is the legitimate belief that Republicans had no right to prevent Barack Obama from filling the vacancy when it opened. But Republicans have already won that fight. So what is there left to win? This is the major source of Democratic confusion. “They should cross the aisle and join Republicans to cut off a filibuster, allowing an up-or-down vote by a simple majority on Judge Gorsuch,” argues Elliott. “That will prevent Republicans from invoking the ‘nuclear option’ to change the Senate rules and abolish the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees.” University of Colorado law professor Melissa Hart endorses the same conclusion. If Democrats filibuster, she warns, “Republicans will eliminate the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations and the selection of judges — both for the Supreme Court and for the lower federal courts — will forever be a purely partisan process.”

It is very odd to argue that Democrats should value the existence of a weapon they can never use. The worst-case scenario for Democrats would be a system in which Republican presidents are able to seat a Supreme Court justice with 50 votes, but Democrats can only seat a justice if they can muster 60 votes. There is a lot of reason to believe this is the system that exists right now. If McConnell can smash all preexisting norms by blockading a Supreme Court vacancy, claim he is doing so in the name of voters, proceed to lose the next presidential election by 3 million votes, and then announce the next nominee will be confirmed sight unseen with or without a single Democratic vote, then McConnell can fill a Court seat any time he has 50 votes.

Elliott argues that Democrats should save the filibuster for the next Supreme Court fight, which she predicts will matter more. And perhaps it will. But the technical existence of the filibuster would not give Democrats any leverage. The importance of the battle would simply increase the internal pressure on Republican senators to hold ranks.

Democrats have nothing to gain by keeping the filibuster on the books. On the other hand, they have a great deal to lose. The last two Democratic Supreme Court nominees were confirmed only because Democrats had near filibuster-proof Senate margins at the time. The last nominee, Elena Kagan, received just 5 Republican votes, and several of those Republicans faced intense backlash from primary challengers for doing so. (Indiana Senator Richard Lugar was defeated in a primary in part because he voted for Democratic justices.)

If the next Democratic president gets a Supreme Court vacancy, he or she will have an extremely difficult time defeating a filibuster. Democrats will probably need to abolish the filibuster for Supreme Court picks to get their justice seated. They may or may not have enough votes to do it. Some of their members (like West Virginia senator Joe Manchin) have political reasons to avoid siding with their party in a high-stakes social-policy fight. Other Democratic senators have expressed institutional reluctance to change the Senate rules. What they need is for Republicans to end the judicial filibuster for them.

McConnell is a norm-violator. That’s what he does. He’s very good at it. Keeping in place an ambiguous set of rules, such as giving the minority a blocking power that the majority openly threatens to eliminate if it is used, is the kind of circumstance under which his tactics thrive. Democrats can eliminate his advantage only if they force the norms and the rules to say the same thing.

The tactical imperative for Democrats lines up neatly with their moral understanding of the battle lines. Democrats object to the Republican Party’s right to nominate anybody to fill the current vacancy. Most agree that if Republicans did have such a right, Gorsuch would make for a highly qualified pick. Their correct tactic is to hold 41 senators together to mount a filibuster on the explicit grounds that the seat belongs to a Barack Obama nominee. Once McConnell eliminates the filibuster, they should support Gorsuch on the final ballot to indicate their endorsement of his qualifications. If, on the other hand, they let McConnell seat Gorsuch without eliminating his own ability to filibuster a Supreme Court nominee later, they may come to regret it.