The stock market keeps hitting record highs. The unemployment rate has fallen to a 16-year low. The economy is growing and wages are rising; the last time consumers were this confident, George W. Bush was a peace-time president.

American politics may be becoming a heavy-handed satire with a spy-movie subplot and life-or-death stakes. The president may be on the cusp of tweeting us into a nuclear war. But when it comes to the economy, Trump’s detractors often seem less outraged by present conditions than by the mogul’s attempts to claim credit for them. Alas, like so many other entities branded by our president, the Trump economy is far less than meets the eye.

His critics are right, however, in thinking that Trump holds little responsibility for the latest gilded mediocrity to bear his name: Our economic woes have less to do with the sordid farce playing out at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue than with the long, drawn-out tragedy that preceded it.

Some of our economy’s short-term trends are genuinely encouraging. But the long-term structural defects that brought us the Great Recession and lackluster recovery haven’t gone anywhere. And in recent weeks, a flurry of new data has thrown those fundamental flaws into sharp relief — and illustrated how our economy’s structural problems have plagued the post-2008 recovery.

Here are five sobering facts to keep in mind the next time green arrows and ebullient stock brokers fill your television screen.

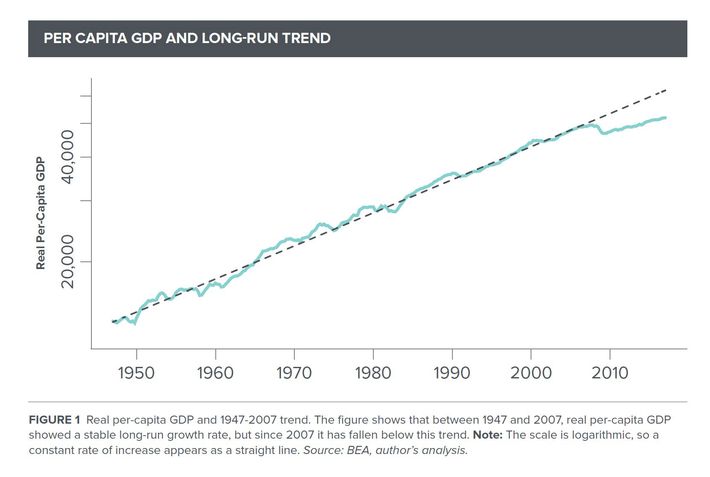

1) America still hasn’t recovered the output it was on pace to produce before the last recession — a failure without precedent in the postwar era.

Between 1947 and 2007, the American economy fell into recession ten times. During each of these downturns, America’s GDP — the total value of goods and services produced by the economy — dipped far below the level it had been on pace to reach before the hard times set in.

But none of those recessions permanently reduced our economy’s productive capacity. And so, when the recovery arrived, America always enjoyed a period of accelerated growth that allowed it to reach — and exceed — its pre-recession potential.

Eight years after the Great Recession ended, we’ve yet to catch up. In fact, growth rates in the recovery’s first years were actually below the pre-crisis average. And while output picked up as the Obama presidency drew to a close, we’ve yet to enjoy a genuine boom. As a result, the gap between our GDP and the level that we were on pace to achieve before the crisis is larger today than it was in 2010.

The Week’s Ryan Cooper spells out the alarming implications of this underperformance:

[I]t’s quite possible that not only are we very far from maximum economic output — meaning literally trillions of economic output gone unproduced every year, and more importantly millions of people left unemployed for no reason — but also that maximum output might be receding ever further over the horizon.

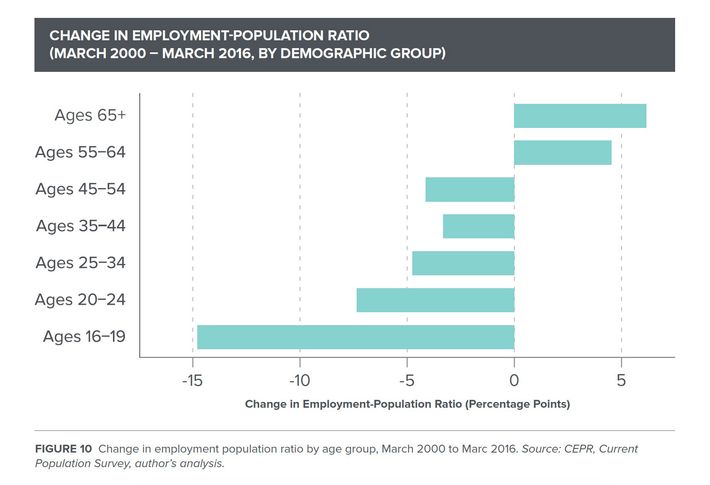

2) The low unemployment rate is largely the product of a sharp decline in the number of prime-age workers looking for employment.

A few years ago, policymakers thought a 4.3 percent unemployment rate would be dangerously low: With a labor market that tight, wages and prices were bound to rise too far, too fast, triggering runaway inflation.

But here we are in 2017, with that piddling unemployment rate — and wage growth and inflation also meager. Which raises the question: If labor is this scarce, why isn’t competition between employers fattening Americans’ paychecks?

There are many right answers to this query. The simplest may be that labor is, in fact, more abundant than the top-line unemployment figures would lead one to believe.

Right now, a little over 4 percent of Americans who are looking for work can’t find it. But that statistic doesn’t account for the abnormally high number of workers who’ve resigned themselves to long-term unemployment.

In 2006, America’s labor-force-participation rate — the percentage of the population that either had jobs or were looking for them — was 66 percent. Today, that figure is 63.

The innocuous explanation for this decline is that America is simply getting older. As Baby Boomers reach their golden years, we should expect the ranks of would-be workers to get thinner.

Economist J.W. Mason rejects this rosy view. And in a new paper for the Roosevelt Institute, he demonstrates that if we accept the standard assumptions about the effects of aging on the workforce, then the graying of America can only account for up to 40 percent of the fall in the worker-to-population ratio since 2007.

The rest of the decline is due to lower participation within demographic groups (as opposed to changes in the demographic composition of the population as a whole). Which is to say, the drop would have occurred even if America were still as young and naïve as it was when Crash won Best Picture.

But Mason contends that even that 40 percent figure is likely too high — because when economists focus on the effects of aging on the labor force, they typically neglect to account for other demographic changes. America has grown older since 2006, but it has also become more highly educated.

“All else equal, older people are less likely to be employed, and educated people are more likely to be,” Mason writes. “Over the past decade or two, these two factors have essentially canceled one another out.”

Thus, if we embrace conventional assumptions about how demographics dictate the size of the workforce, virtually none of the decline in labor-force participation can be attributed to demographics.

Regardless, the retirement of the Baby Boomers can’t explain the bulk of the decline. So, what can?

Higher rates of college attendance can account for the drop among the youngest workers. But for the rest, the likely explanations are grimmer. The Great Recession significantly changed the composition of jobs in our economy. When the recovery returned, many middle-aged workers found that the skills they’d cultivated over decades were no longer in demand. For others, the sheer length of the recession, and weakness of the recovery, led to long-term unemployment, demoralization, and, in dire cases, addiction. Rates of alcoholism and drug abuse have been on the rise since 2008.

These distinct forms of adversity were exacerbated by a more common affliction: For a wide array of Americans, work just doesn’t pay like it used to.

3) The number of Americans working multiple jobs is at a 20-year high, while underemployment remains above pre-recession levels.

One testament to the lackluster quality of jobs in today’s economy is the high number of Americans who are working more than one. Last month, that figure rose to 7.6 million, a two-decade high. For most workers, this fact reflects financial desperation, not entrepreneurial vigor, according to economist Komal Sri-Kumar.

“The principal reason workers hold more than one position is that no single job provides a sufficient income,” Sri-Kumar wrote for Business Insider earlier this month. “In a robust economic recovery, the number of full-time workers should be rising, and the number of workers employed part-time or holding multiple jobs, should decline.”

Meanwhile, the percentage of underemployed Americans — workers who have part-time jobs but want full-time ones, or else who have left the workforce involuntarily (because they no longer believe they can find a job that matches their skills and needs) — stands at 8.6 percent. In 2007, that figure fell as low as 7.9 percent; one month before the onset of the Great Recession, it was 8.4.

Things could be worse, of course. During the crisis, underemployment climbed above 17 percent. And while wage growth is underwhelming, for many Americans, it’s a relief to see any at all. Median household income barely budged during the recovery’s first five years, before making significant gains in 2015 and 2016.

What makes the underemployment data truly dispiriting is that this is about as good as policymakers expect things to get. The Federal Reserve has already begun raising interest rates, claiming that America is now at — or near — full employment.

Eventually, the business cycle will turn down again. We are ostensibly close to the recovery’s peak; and millions of Americans lack the full-time employment they seek, while millions more have lost all hope of finding it.

Defenders of the central bank will note that rates remain historically low, and were kept near-zero for seven years. Such extraordinary measures have negative side effects. And if the Fed doesn’t start raising rates now, it will have little room to provide monetary stimulus in the event of future downturn.

Whatever the merits of this argument, it raises the question: Why is it that all this monetary stimulus has yielded such modest returns? Why, after all this time, is demand still insufficient to produce the “catch-up” boom that economists once thought inevitable?

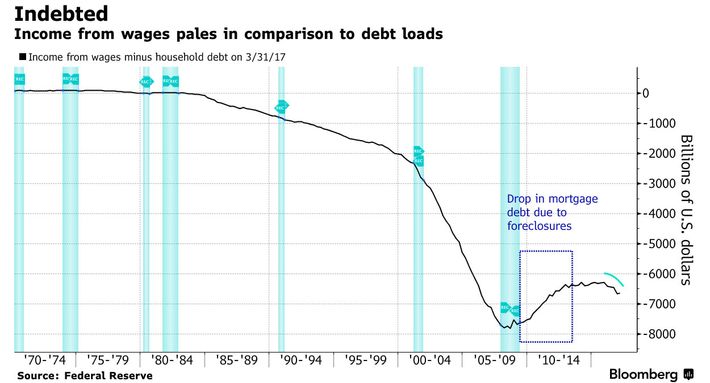

4) Americans are taking on record amounts of debt, just to finance the basic necessities of middle-class life.

The 2008 crisis had many causes, both proximate and structural. Among the latter was the desire of America’s public, corporate sector, and elected representatives to maintain middle-class living standards in an era of stagnant wages. To avoid being priced out of the American dream, working families took on massive amounts of mortgage and credit-card debt. Lenders and regulators were eager to enable such outsize borrowing, while economists dutifully provided elaborate rationalizations for its sustainability. On the eve of the crisis, household debt in the United States peaked at $12.68 trillion. Today, that figure is $12.7 trillion.

Now, there are important distinctions between our current debt level and that of nine years ago.The economy is, of course, larger than it was in 2008. Back then, $12.68 trillion was equivalent to 85 percent of the economy; today, our marginally higher sum is equivalent to 67 percent. And the composition of our current debt is much different. Americans owe far less on their houses and credit cards these days, with a greater percentage of household debt going toward (ostensibly safer) auto and student loans. And, in the aggregate, borrowers are paying far lower interest rates on their debt now than they were before the crisis.

But the fact that U.S. consumers aren’t quite as over-leveraged as they were in the fall of 2008 should be of little comfort: Right now, American families are racking up record levels of debt just to secure access to education and transportation — which is to say, for basic necessities of middle-class life.

This kind of borrowing may not be so unsustainable as to trigger a financial crisis. But it’s more than burdensome enough to take a toll on demand. As Bloomberg’s Vince Golle notes, personal-spending growth has averaged a mere 2.4 percent since the recession ended in 2009. During the previous expansion that figure was 3 percent; between 1982 and 1990 it was 4.3.

“This increase in leverage has sapped our ability to spend,” Lance Roberts, chief investment strategist at Clarity Financial LLC, told Golle earlier this month. “I think we’re stuck.”

There may be few better explanations for the current recovery’s anomalous weakness than this chart:

For the first time since World War II, the American economy has come out of a recession growing too slowly to catch up to its previous potential. During that time, household debt had outstripped income to a degree not seen at any time in the modern era — except for the years immediately preceding the last crisis. It is reasonable to suspect that there’s a connection between these facts.

But if our underwhelming expansion is a product of the middle class’s historic reliance on debt, what explains that reliance?

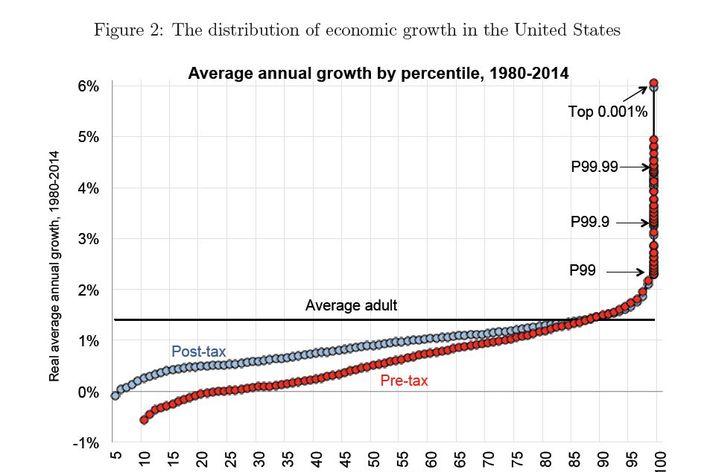

5) The superrich are hoarding damn near all of the economic growth.

Last month, three of the world’s leading chroniclers of inequality — the economists Emmanuel Saez, Thomas Piketty, and Gabriel Zucman — unveiled their latest eye-popping illustration of the class war that almost all of us are losing.

Conservative economists (in their characteristic complacence about economic inequity) have long argued that popular accounts of income inequality exaggerate disparities by failing to price in the benefits that Americans receive, both from the government and their employers.

So, in their latest research, Saez and Co. sought to account for all forms of pre- and post-tax income. The chart above factors in the cost of employer-provided health care, pensions, food stamps, Medicaid, and a variety of other private and public benefits. And the story remains the same: The superrich are hoarding income gains to a degree without precedent in the postwar period.

Over time, this has translated into an even more gargantuan disparity in wealth, as Matt Bruenig of the People’s Policy Project recently observed.

The right has long argued that attempts to reduce inequality come at the cost of growth and innovation. Our new Gilded Age has made a joke of that notion. The extraordinary inequality of the post-Reagan era hasn’t just mocked popular intuitions about economic fairness, eroded social trust, and given idiosyncratic billionaires unprecedented influence over politics — it has also left us with historically weak growth in GDP and productivity.

As working people were forced to accept a smaller and smaller share of national income, they became more and more dependent on credit to maintain their consumption habits — and, thus, our nation’s economic growth. Meanwhile, the wealthiest people in our society didn’t just accrue more money than they could spend, but more than they could usefully invest. There are only so many ways to turn a profit when the middle class’s capacity to spend is depressed by its mounting interest payments. These days, the “job creators” just plow ungodly sums of capital into bidding up the price of urban real estate.

The historic weakness of this post-crisis expansion has less to do with inescapable, economic realities, than with contingent, political ones. Our nation is rich in idle labor and unproductive capital. Transferring wealth and income from the superrich to the broader populace — through new social spending and jobs programs — is all but certain to increase demand, which would produce a tighter labor market and higher wages, which would increase the incentive for employers to invest in automation, and, thus, boost productivity.

All of which is to say: Our economy can get better. But first, we’re going to have to admit that we have a problem.