The Senate GOP’s plan to overhaul the American tax system has been around for less than two weeks. The party has not held a single hearing on the bill’s macroeconomic effects (even as experts warn that these could include a health-care crisis and housing market crash). Large majorities of the public disapprove of the legislation. Even small-business owners — ostensibly, one of the tax package’s chief beneficiaries — appear to oppose it.

And Mitch McConnell plans to pass the bill out of the Senate by week’s end.

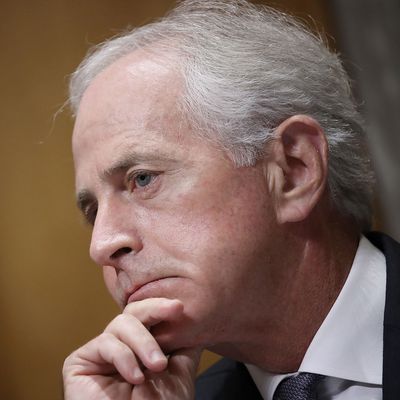

As of this writing, at least nine Republican senators aren’t sure that that’s a good idea. Ron Johnson and Steve Daines worry the bill favors corporations over (so-called) small businesses. James Lankford, Bob Corker, Jeff Flake, and John McCain have all expressed reservations about the legislation’s (enormous) impact on the deficit. Jerry Moran isn’t crazy about killing Obamacare’s individual mandate. Lisa Murkowski and Susan Collins are Lisa Murkowski and Susan Collins.

To stay on schedule, McConnell needs to pacify Corker and Johnson by Tuesday. That’s when the Budget Committee plans to vote on whether to advance the tax package to the Senate floor. Assuming he pulls that off, the Majority Leader will need to win over five of the remaining seven holdouts by Friday (McConnell can only afford to lose two votes). If the Senate GOP can’t find consensus on a bill by week’s end, the Trump tax cuts could get kicked to next year, since the government will run out funding in 11 days, and Republicans still need to hammer out a bipartisan spending bill to avert a shutdown.

If the tax legislation is pushed to 2018, the GOP leadership will spend the holidays getting chewed out by disgruntled donors, while the bill’s losers would have time to get informed and organized. Most critically, McConnell’s margin for error could shrink to one in January, thanks to Roy Moore.

So, Republicans want to get this done now. Here’s how they plan to do that:

Make the bill even better for rich business owners, to win over Johnson and Daines.

Most firms in the United States don’t pay the corporate income tax. Instead, theses companies’ profits pass through to their owner’s individual returns. This means that, at present, highly profitable “pass-through” businesses are taxed at the top individual rate of 39.6 percent, while corporations (statutorily) pay 35 percent.

The House tax bill would slash the corporate rate to 20 percent, and the pass-through rate to 25. The Senate version includes that same corporate cut — but establishes no new, special rate for pass-throughs.

Instead, the bill creates a 17.4 percent income-tax deduction for owners of pass-through businesses, no matter their income level. This change actually makes the Senate bill better for genuinely small businesses than the House version was: Right now, the vast majority of small business owners pay 25 percent or less on their (modest) business income. So, for them, a large tax deduction is worth way more than a ten-point cut in the top rate.

But for rich, pass-through business owners — like, say, Senator Ron Johnson of Wisconsin — the Senate bill is a disappointment. “I just have in my heart a real affinity for these owner-operated pass-throughs,” Johnson recently told the New York Times. Montana senator Steve Daines shares Johnson’s concerns.

McConnell hopes to win them over by increasing the tax deduction for pass-throughs from 17.4 to 20 percent.

Put in a $10,000 property tax deduction — and scrap the state-and-local tax deduction for corporations — to win over Susan Collins.

Collins’s biggest objection to the bill appears to be its repeal of Obamacare’s individual mandate. And Kansas senator Jerry Moran has also expressed opposition to that measure. But killing the mandate generates $300 billion in much-needed revenue. Thus, the GOP leadership hopes to appease Maine’s favorite moderate by honoring one of her other requests — a $10,000 property tax deduction.

Right now, the Senate bill would abolish the state-and-local tax (SALT) deduction. This provision would add more than $1 trillion in revenue by hammering upper-middle-class households high-tax (a.k.a. blue) states. In the House, the GOP’s reliance on Republican lawmakers from New York, New Jersey, and California has forced the party to soften the blow to these areas, by preserving a $10,000 property tax deduction.

Since no Senate Republicans represent those coastal elites, McConnell’s initial bill scrapped SALT in its entirety. Now, Susan Collins wants what the House is having. And the Senate Majority Leader is inclined to give it to her — after all, putting the property tax deduction back in would make it easier for Paul Ryan to pass the Senate bill through the lower chamber.

But there’s a catch: Including a property tax deduction would make the Senate bill upwards of $100 billion more expensive over the next decade. And McConnell only has about $80 billion to play with — and that’s before factoring in the cost of making the bill more generous to pass-through businesses.

The Senate leadership thinks it can (partially) solve this problem — and address one of the bill’s biggest public-relations headaches — simultaneously. Currently, the Senate bill allows corporations to retain the state-and-local tax deduction, even as it forces middle-class families to do without it. This has provided Democrats with (yet another) easy attack line. Now, Republicans are thinking about taking SALT away from corporations, and using the new revenue to meet their holdouts’ demands.

Give Lisa Murkowski some oil.

The Alaska senator has long called for opening her state’s national wildlife refuge to oil drilling. Republicans are expected to add a provision to their tax bill that would do just that.

Let the deficit hawks eat wildly optimistic growth projections.

Four Senate Republicans have expressed concerns about the bill’s (enormous) impact on the deficit. Three of these senators — Bob Corker, Jeff Flake, and John McCain — have nothing to lose in tanking the bill (politically, anyway). And it is impossible for McConnell to meaningfully address their concerns.

As written, the Senate tax bill would add $1.5 trillion to the deficit over the next decade. The legislation is deficit-neutral after that — but only because it phases out all of its middle-class tax cuts in 2026, while keeping many middle-class tax increases in place. And the GOP leadership has been assuring the public that it will be politically impossible for any future administration — Democratic or Republican — to let those popular tax breaks expire. Which is to say: McConnell’s official line is that his bill isn’t actually a deficit-neutral plan to finance a corporate tax cut by soaking the middle class — it’s just a giant, unfunded, across-the-board cut loaded with budget gimmicks that mask its true price.

There is no fiscally conservative version of this legislation. You can’t deliver giant corporate and individual tax cuts — while maintaining defense and entitlement spending at their current levels — without drastically increasing the the national debt. And the GOP doesn’t have the votes to buck the Pentagon, or their own elderly base.

Thus, Republicans have to hope that their deficit hawks are all squawk, no bite — or else willing to believe that the bill would generate so much growth, the tax package would pay for itself.

For the moment, the hawks don’t seem to be buying it.