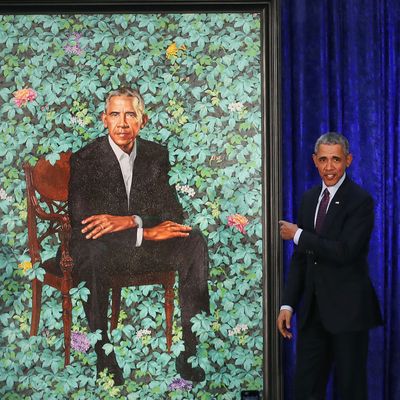

Yesterday, the National Portrait Gallery unveiled the official portraits of former president Barack Obama and former First Lady Michelle Obama, painted by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, respectively. They’re both very nice, for many reasons that historians and art experts can articulate much better than I.

Obama’s portrait, activist Brittany Packnett wrote, “dismantles so much and creates new visions of masculinity that black men rarely have the public permission to explore.” The Times’ Holland Cotter noted, “Whereas Mr. Obama’s predecessors are, to the man, shown expressionless and composed, Mr. Obama sits tensely forward, frowning, elbows on his knees, arms crossed, as if listening hard.”

Like all works of art, good or bad, the paintings are open to interpretation. Maybe you saw what Packnett and Cotter did. Or maybe you saw, in the former president’s depiction, set against a curling green overgrowth, Homer Simpson, sinking slowly into a hedge.

This GIF, which has been floating around cyberspace for the last half-decade, comes from the 1994 episode “Homer Loves Flanders.” Its utility is obvious: Have you done something embarrassing and want to exit the situation without making things worse? Well, there’s the Homer-hedge GIF. Is there a ton of drama happening online that you want no part of? There’s the Homer-hedge GIF. The comparison between Wiley’s portrait and the iconic Simpsons moment is obviously meant as dumb fun, but it has an emotional resonance: a former president, watching from the sidelines, exiting quietly into history as his successor turns American politics into a petty, dysfunctional, egotistical mess.

While there is no official internet Hall of Fame or governing body to determine what would be in it, it’s safe to say that the Homer-hedge GIF would make the cut. So would “Loss,” an infamous webcomic whose four-panel structure became so recognizable it worked as a punchline. Another meme, a photo of a young man standing on a sidewalk with his hands clasped, might have a shot. Like “Loss,” it quickly became a game of Spot the Meme, where the man’s stance became the joke in and of itself.

Online, in the ever-more-influential world of digital culture, the ability to create conceptual links is prized as wit. Can you take one joke and attach it to another? Can you see how this image references the other? Beyond memes, you find social-media users like Tabloid Art History, who help spur a culture linking famous images of the past with the popular (if not capital-A artistic) meme images that dominate digital culture today.

The acceleration of this trend — the uniquely human talent of pattern recognition now distributed at scale — does more than break down the barrier between high art and kitsch even further. (A barrier Wiley himself has been chipping away at with humor for his entire career.) It overloads our images with meaning. The web is built on the concept of links: One page to another, to a third, to a fourth, each branching off endlessly, all pages attached together in an eternal and endless chain of reference. Painters no longer only evoke life, or other art, or meaning — but also any of the near-infinite number of images captured and archived digitally and floating around the internet, in a land of context and reference and meaning so endless and mutable and open it ceases to be context or reference or meaning at all.