One of the abiding realities of U.S. politics is that young voters don’t participate proportionately in midterm elections. This is not a new thing. But it’s become a big thing for Democrats in the 21st century as age has become a major partisan differentiator, with older voters tilting Republican and younger voters trending Democratic.

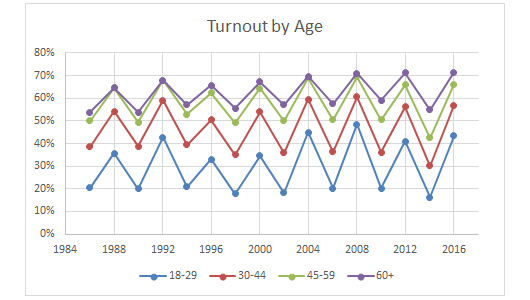

The chart below shows that while every age category turns out more in presidential than in midterm elections, and old folks vote more than younger folks in every election, the midterm drop-off is much more severe for under-30 voters.

There are varying theories for why younger voters tend to skip midterms (and other non-presidential contests), which is not just an American phenomenon. This explanation from the Economist offers one of the most plausible:

[Y]oung people today do not feel they have much of a stake in society. Having children and owning property gives you a direct interest in how schools and hospitals are run, and whether parks and libraries are maintained. But if they settle down at all, young people are waiting ever longer to do it. In 1970 the average American woman was not yet 21 years old when she first married, with children and home ownership quickly following. Today women marry at 26 on average, if they marry at all, and are likely to want a career as well as children. People who have not settled down are not much affected by political decisions, and their transient lifestyles can also make it difficult to vote.

A presidential election with its national scope (and rules allowing even highly transient people to vote) and incessant publicity are more likely to attract young voters. But midterms often leave them cold.

But there are now signs that could change this year.

A new SurveyMonkey poll shows a really high level of interest among young voters this year:

[A] new poll from Cosmopolitan and SurveyMonkey finds that young adults are deeply dissatisfied with their elected representatives and unusually motivated to vote in both sets of elections [primaries and the general election] in 2018. The online survey of a national sample of 4,706 adults, conducted from February 22-25, found that 60 percent of young people (ages 18-34) say they’re absolutely certain to vote or will probably vote in the upcoming primary elections, and 68 percent say the same of the midterm elections. By contrast, less than half (47 percent) of young people say they always or nearly always voted in past primary elections, and only 25 percent say they voted in the 2014 midterm elections.

The huge gap between self-reported interest in the midterms and past voting behavior is going to become a big issue in polls later in the year, since some pollsters base likelihood to vote primarily on one of these two very different factors. And there’s some doubt that a lot of young voters who might want to vote know enough about local politics to participate, particularly in primaries.

Turnout in the year’s first primary election, which took place on March 7 in Texas, was higher than usual among people who don’t usually vote in off-year or primary elections. But it wasn’t as high as many polls had predicted, which may be a reflection of another finding from the Cosmopolitan/SurveyMonkey poll: Many young people don’t know when their state’s primary will be held, and relatively few say they’re familiar with the candidates running to represent them at the state or local level.

But by November, a lot more voters of all ages will have heard that the midterm general election is a referendum on the occupant of the White House, and that happens to be something about which under-30 voters have strong opinions right now:

More than half (53 percent) of young people say the results of the 2016 presidential election are making them more likely to vote in this year’s general election. Only 30 percent approve of the way Donald Trump is handling his job as president, and a majority (52 percent) strongly disapprove of the president’s performance so far.

It’s the intensity of this antipathy towards Trump that may matter most. Young voters famously liked Barack Obama a lot. But that didn’t motivate them to turn out for his party in either 2010 or 2014.

Without question, it would be ironic if Obama’s successor discovered the key to the ancient riddle of how to get young people to vote in midterms — by horrifying them. If that happens, the Democratic wave so many are anticipating could grow even larger than expected.