For years, Morgan (name changed for privacy) found fulfillment in the simple act of putting a paintbrush to canvas. Art had long been a source of her joie de vivre — and perhaps, on a deeper level, it provided solace when the pressures of the world seemed too great a burden to bear.

Slowly, though, darkness crept in. It started with a loss of inspiration, and eventually led to complete apathy toward the pastime that had once provided so much joy. Morgan found herself in a downward spiral, which became compounded by stressors in her personal life.

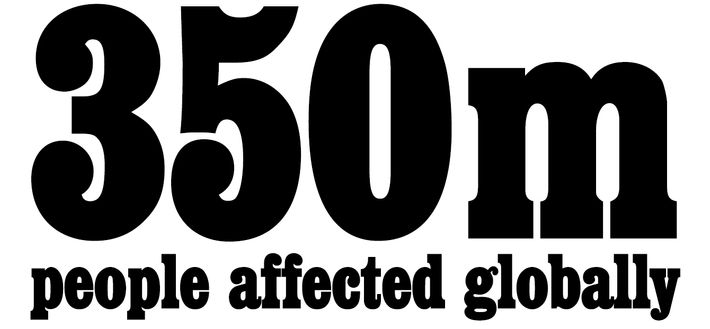

You’re probably already familiar with the disease that was sapping Morgan’s vitality. There’s a strong chance that depression has affected the lives of people you care about — or maybe even your own. Depression affects some 350 million people globally, and it’s as indiscriminate as it is insidious: no two cases are exactly alike.

It’s a cruel cycle of an innately isolating disease making people even more isolated, explains Dr. Michelle Craske, director of UCLA’s Anxiety and Depression Research Center. Because of social stigma and self-judgment, people experiencing depression sometimes feel they have no choice but to suffer in silence — often with dark consequences. There are approximately 800,000 suicides each year, some 90 percent of which the World Health Organization associates with mental disorders. More shockingly still, depression accounts for more fatalities each year than car accidents.

But one ambitious project aims to improve both the taboo perception of depression and the scientific tools the medical community is armed with to combat the disease. Just over two years underway, UCLA’s Depression Grand Challenge (DGC) hopes to cut the global impact of depression in half by 2050. UCLA is using a four-pronged, interdisciplinary approach that combines the expertise of around 100 researchers across 25 university departments. It centers on a decade-long, 100,000-person study — the largest of its scope and scale in history. UCLA’s comprehensive efforts are helping fight this quietly devastating disease — and giving people like Morgan their lives back.

New Tactics for Tackling Old Challenges

Despite its prevalence, depression is something we still don’t fully understand. The causes – intersecting environmental, biological, and genetic factors – remain difficult to untangle, and research is notoriously underfunded worldwide. To complicate matters, “depression” is an umbrella term, encompassing different symptoms rather than a single set of easily diagnosable symptoms.

To tackle this complex condition, the DGC unites a community of scholars spanning different disciplines uniquely poised to approach problems from a 360-degree perspective. “We have clinical scientists like me, engineering scientists, computational scientists, people working in social sciences and art,” explains Dr, Craske. “The fact that everybody is coming together to tackle this problem … I’ve just never seen this before,” she says. “We believe we can have an impact, but we have to do it together.”

The DGC consists of four main components. The first is the aforementioned 10-year-long, 100,000-participant study, a.k.a. the 100K Study. Today, the study is in its infancy, but it promises to eventually boast the largest and most comprehensive data collection about depression to date. “The goal is to be able to get genetic information from 100,000 individuals to identify what the risk factors are,” explains Dr. Kelsey C. Martin, a neuroscientist and dean of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. Thanks to genome-sequencing technologies, researchers can find links or genetic signatures that may indicate a predisposition for depression, or even the types of therapy most likely to work for a particular individual.

UCLA expects that nearly 50 percent of the 100K Study’s participants will need treatment, which is where component two, UCLA’s Innovative Treatment Network (ITN), comes in. This part of the challenge folds long-standing UCLA programs, such as the research and treatment center where Dr. Craske works, into an overarching scheme.

One critical success metric for the ITN is devising and implementing scalable solutions like remote symptom-monitoring via smartphones and wearables. The idea behind these types of efforts is to personalize experience-based treatment options for each patient. “There’s a lot of room for trying to figure out how to monitor depression,” explains Dr. Martin. “For example, how do we use wearables that will provide information about activity, about circadian rhythms of sleep, about even potentially being able to monitor the aspects of an individual’s voice, to monitor social interactions?” She cites one ongoing area of study the engineering team is involved with, which uses wearables to measure metabolites in sweat.

Next comes neuroscience. By studying the brain and cellular basis of depression, UCLA hopes to further our understanding of the disease. This facet of the DGC ties neatly into the 100K Study: Data will inform new areas of research that will lead to treatment options. One highlight is the work UCLA is doing with neurotransmitters. “We have one project that’s trying to look at some really basic cell biology of that signaling pathway,” says Dr. Martin. “When we understand that, we can start to develop better treatments.”

Combating Stigma With Science

Overcoming the social stigma surrounding depression is the fourth component of the DGC. Research, outreach, and education to combat stigma is part of what Dr. Craske refers to as the challenge’s “Awareness and Hope” campaign.

“Part of therapy has to be human interaction, and stigma isolates people because it makes them feel that they can’t share their experience with others,” says Dr. Martin. “The social stigma certainly has negative aspects for any type of therapy for depression, but it also has negative impacts for just gaining the information that’s required to really understand this incredibly common human experience, because people don’t talk about it.”

Both Dr. Craske and Dr. Martin compare reducing the stigma of depression to that of cancer 20 years ago. “[We need to make it] a topic of discussion rather than something to shy away from or to avoid or to hide,” says Dr. Craske. Simply by way of existing, the DGC has already started to open up the conversation. “Whenever I go to any kind of a setting where there’s a discussion of the Depression Grand Challenge, it’s a way of giving permission to people to recognize that there’s nothing shameful about depression and that they’re not alone,” says Dr. Martin.

By uncovering the scientific basis of depression and spreading these learnings, UCLA works towards changing society’s unfortunate propensity to blame the sufferer. “The whole goal of the 100K project and some of the basic science projects we’re undertaking [is to] try to understand what’s causing [depression], as opposed to it being somebody’s quote-unquote ‘fault’ for feeling depressed,” says Dr. Martin.

The Road Ahead

Morgan is one of the program’s success stories. As a result of a cognitive treatment plan based out of UCLA’s Anxiety and Depression Research Center, she was able to slowly introduce art back into her life. She started by visiting museums again, eventually working her way toward picking the paintbrush back up. “She’s very appreciative that she could regain that pleasure, which made it that much easier to manage all the other stuff that was going on in her life,” says Dr. Craske.

Stories like this are, hopefully, just the tip of the iceberg. “We have a lot of challenges in the world,” says Dr. Martin. “I think about climate [change], socio-economic issues, all of those human challenges that require creativity, boldness, human capital — and depression really corrodes the human ability to solve problems. It’s a tremendous loss in terms of what human beings are capable of.”

If UCLA achieves what it has set out to do — that is, cut the global impact of depression in half by 2050 — the DGC will not only help millions of individuals, it could also impact society as a whole, charting the course of our very future.

This is paid content produced for an advertiser by New York Brand Studio. The editorial staff of Daily Intelligencer did not play a role in its creation.