The United States, circa 2018, looks like a place run by people who know they’re going to die soon.

As “once in a lifetime” storms crash over our coasts five times a year — and the White House’s own climate research suggests that human civilization is on pace to perish before Barron Trump — our government is subsidizing carbon emissions like there’s no tomorrow. Meanwhile, America’s infrastructure is already “below standard,” and set to further deteriorate, absent hundreds of billions of dollars in new investment. Many of our public schools can’t afford to stock their classrooms with basic supplies, pay their teachers a living wage, or keep their doors open five days a week. Child-care costs are skyrocketing, the birth rate is plunging, and the baby-boomers, retiring. And, amid it all, our congressional representatives recently decided that the best thing they could possibly do with $1.5 trillion of borrowed money was to give large tax breaks to people like themselves.

There are many plausible explanations for why America has embraced “carpe diem” as its governing philosophy. Our ruling political party is dominated by geriatric billionaires and millenarian Christians; our electoral system gives politicians little incentive to prioritize the nation’s long-term well-being over their constituents’ immediate gratification; and the conservative movement’s decades-long assault on “big government” has constrained the public sector’s capacity to invest in the future. But all these causes of American misrule are informed and exacerbated by this overriding fact: Young people vote much less than those who aren’t long for this Earth.

Although America’s voting-age population includes a roughly equal number of millennials and baby-boomers, the 2016 electorate featured 14 million more of the latter. Voters under 30 backed Hillary Clinton by 18 points — but their verdict drowned out by those over 65, who favored her opponent by eight.

The consequences of that election have not persuaded America’s (predominantly left-leaning) millennial nonvoters of the importance of political participation. A new survey from PRRI and The Atlantic suggests that only one-third of 18-to-29-year-old voters are certain to cast ballots next month. Among Donald Trump’s cohort, that figure is 81 percent.

Some portion of this disparity is probably inevitable — there is no democracy in the world where the young outvote the old. Still, millennials in the U.S. are more underrepresented than their peers in most other developed countries. Primary responsibility for this fact lies with our nation’s political parties, which have made America an exceptionally difficult place to cast a ballot. If Democrats wish to increase turnout among the young, they’d be well advised to implement automatic voter registration, a new Voting Rights Act, and a federal holiday on the first Tuesday in November, when and if they have the power to do so. More immediately, Team Blue could try adopting policies popular with the kids these days, such as student-debt relief, marijuana legalization, and approaches to universal health care that don’t involve jacking up the price of health insurance for 20-somethings, and then forcing them to buy it.

But if America’s suppressive voting laws, and the Democrats’ political failings, are the biggest obstacles to smashing the gerontocracy, they aren’t the only ones. There is also the fact that many of my fellow millennials have very wrong opinions about how politics works.

Specifically, PRRI finds that 39 percent of Americans under 30 say that they do not vote, or engage in any other form of political participation, because doing so “wouldn’t make a difference”; 49 percent say that they do not “know enough about the issues” to get involved in politics; and 9 percent believe that voting is less important than “being active on social media,” which is the “most effective way to create change” (granted, sharing Intelligencer’s political reporting and analysis on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Snap, Pinterest, Venmo, and Friendster is the most effective way to bend the moral arc of history toward justice, but it is unlikely that that was what most respondents meant when they said “being active on social media”).

Now, politically disengaged millennials aren’t known for reading a lot of articles about millennial political disengagement. But, if there happen to be some nonvoters out there who stumbled upon this whilst searching for cheat codes for Fortnite, recipes for avocado toast, or abstract concepts to “kill,” please consider the following evidence that your vote would make a difference — perhaps, even the difference — in averting our democracy’s collapse into senescence.

1) Boomers get a big bang for their ballots.

Last year, Donald Trump’s GOP tried to slash Medicaid in the middle of a “public health emergency” that was concentrated in red America; made it easier for payday lenders to exploit cash-strapped veterans; restored the right of serial labor-law violators to compete for federal contracts; and responded to the student-debt crisis by relaxing federal oversight on predatory, for-profit colleges.

Which is to say: There are very few things that America’s governing political party isn’t willing to do to please its reactionary donor class.

But taking socialism away from baby-boomers is one of them.

Despite its ruthless disregard for the most basic interests of most Americans — and the Koch Network’s aching desire to cut “entitlements” — the Republican Party doesn’t have the stomach to mess with boomers’ beloved socialized medicine and basic income programs. Of course, many GOP lawmakers do support cuts to Medicare and Social Security — but only for when you need it, dear millennial reader. As Marco Rubio explained during a primary debate early in the 2016 cycle, “Everyone up here tonight that’s talking about reforms [is] talking about reforms for future generations. Nothing has to change for current beneficiaries.”

There is no technocratic rationale for this position. Millennials and Gen-Xers will, on average, have much lower lifetime earnings than the exceptionally lucky boomers did — and thus, will be more reliant on Social Security in their golden years. The GOP’s deference to current beneficiaries is purely a testament to older voters’ political power. And AARP members do not owe their immense clout to the militancy of their street protests — or the wit of their Twitter “owns” — but merely, to their singular propensity to show up at the polls.

Millennials have the numbers to make student debt-relief, public day care, a federal ban on mayonnaise, or any other policy priority of younger Americans into an object of bipartisan consensus (which is to say, into something that Republicans must try to kill quietly through judicial fiat, instead of loudly through legislation). If 71 percent of eligible voters under 30 cast ballots this November (as 71 percent of those over 65 did in 2016), the American government would become drastically more responsive to their interests.

2) If voting changed anything, they would make it illegal — and they are.

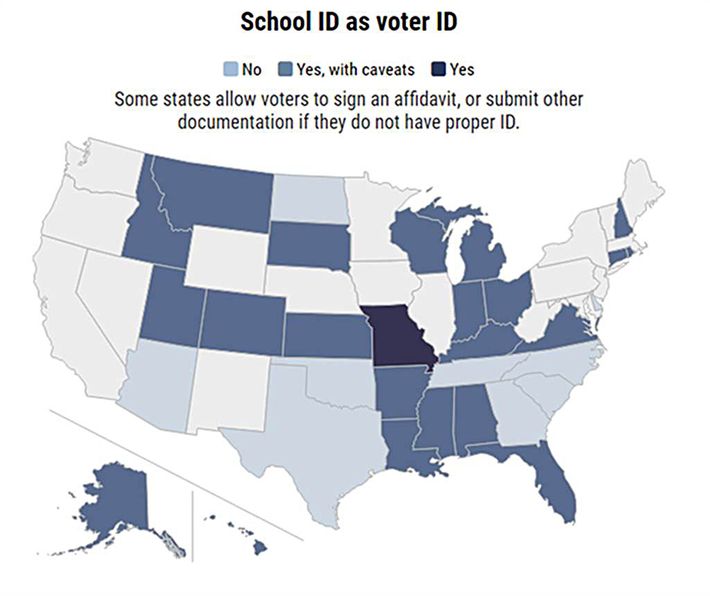

In 2008, an uptick in turnout among young voters helped deliver North Carolina to Barack Obama. Shortly thereafter, Republicans in the Tarheel State’s government revised North Carolina’s Voter ID law to exclude student identification cards. Eight other states have adopted similar restrictions.

Just this year, New Hampshire passed a law that effectively imposes a poll tax on college students who wish to vote in the Granite State; Florida’s Republican governor (and Senate candidate) Rick Scott tried to block early voting on university campuses; state legislators in North Dakota have straight-up disenfranchised just about every millennial (and Gen-Xer and boomer) who lives on a Native American reservation; and down in Georgia, the Republican gubernatorial candidate is also the acting secretary of State — and is using the authorities of his office to purge voter rolls and deny registration applications, in an ostensible bid to customize the electorate he will face in November.

Millennials might doubt their ability to make change at the ballot box — but the powers that be sure don’t.

3) The median millennial voter understands “the issues” better than the average American.

If Donald Trump “knows the issues” well enough to be president, then you, hypothetical non-voting millennial reader, are well informed enough to vote.

In fact, there’s a good chance you understand the problems facing our country better than the average American. According to Pew Research, millennials are more likely to accept the reality of climate change than any other generation of Americans, with 81 percent saying there is solid evidence that the Earth is warming — a factual statement that only 69 percent of baby-boomers are willing to endorse. What’s more, millennials are the only generation in which a supermajority (correctly) attributes climate change primarily to human activity.

Millennials are also, by far, the most racially progressive generation in the electorate. A majority of younger Americans say that Islam “does not encourage violence more than other religions,” and that discrimination is the primary reason why African Americans “can’t get ahead these days” — sentiments that majorities of boomers and Gen-Xers reject. Thus, an America in which millennials voted in high numbers would be one where Republicans would have a much harder time burying their unpopular policy positions beneath attacks on Colin Kaepernick and sanctuary cities. Which is to say: The mass entrance of millennials into the electorate would likely lead to a more substantive political debate, as demagogic appeals to racial paranoia would lose much of their efficacy.

More concretely, as mentioned above, millennials are by far the most pro-Democratic — and anti-Trump — generation in the U.S. Which is to say, they are the generation most likely to recognize the reality that Donald Trump and his party are a threat to our republic.

Beyond their (singularly correct) ideological instincts, millennials also boast important insights into many public-policy issues, simply as a function of their generation’s lived experience and material realities. For example, American housing policy is profoundly biased in favor of homeowners, and this reality has has generated housing shortages in many major American cities, thereby undermining economic growth. The overrepresentation of boomers in the electorate perpetuates these problems, due to that generation’s high-levels of home ownership.

By contrast, a sharp increase in voter participation among millennials — only about 34 percent of whom own homes — would likely increase the salience of renters’ interests in U.S. politics. Similarly, the existing electorate is much less likely to appreciate the severity of the student-debt crisis than millennials are, or to comprehend the broader material challenges that younger Americans face: Despite the fact that the United States does far less for its young people (in terms of subsidizing education, job training, housing and child care) than just about any other advanced democracy, a majority of boomers say that the government “does enough for young people” (but still needs to do more for older folks).

To be sure, increasing turnout among millennial voters, by itself, will not bring about the kind of sweeping, social democratic and environmental reforms that our country needs, and which many young Americans desire (a recent BuzzFeed poll found that 39 percent of millennial men and 22 percent of millennial women consider themselves “socialists”). Our current government is more responsive to demographic groups that vote a lot than to those that don’t — but there are still plenty of boomers in this country who are drowning in medical debt, struggling to pay the rent, and/or, resigning themselves to spending the entirety of their “golden years” working menial jobs to make ends meet. Millennials aren’t wrong to think that their individual votes won’t be sufficient for creating the America they seek — an America where prosperity is broadly shared, energy use is environmentally sustainable, and mayonnaise is a Schedule 1 substance.

Nevertheless, the path to that better world begins at your local precinct. So please, fellow kids, put down your selfie sticks, quit your Twitch-ing, and “Pokémon-Go-to the polls” this November.