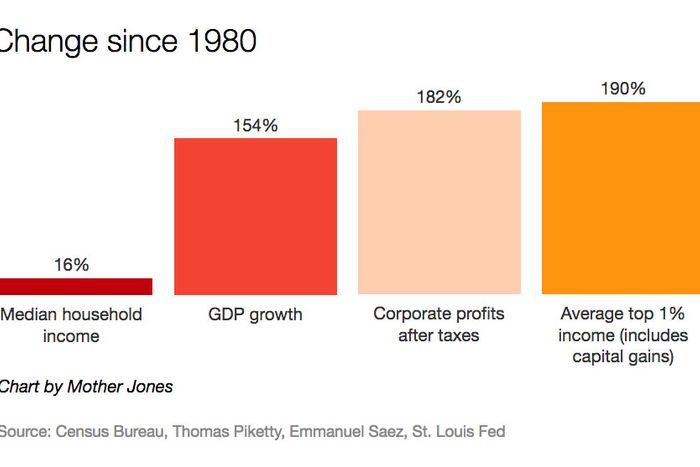

When Ronald Reagan took office, affluent Americans paid a 70 percent tax rate on all income above $216,000. In the decades since, our country’s highest earners have seen their annual pay skyrocket, while the median household’s has barely budged. As a result, America’s 160,000 richest families now lay claim to 90 percent of its wealth. Studies suggest that this kind of inequality erodes social trust, abets plutocracy, and depresses economic growth. Politicians from both major parties routinely suggest that they see inequality as a major problem.

The case for trickle-down economics — which is to say, the idea that high top-marginal tax rates hurt economic growth — is much weaker now than it was in 1980. The U.S. saw faster GDP and productivity growth in the decades before Reagan’s tax cuts, than it did in the decades after. And during that latter era, the American economy grew at roughly the same rate as peer nations with higher top tax rates. A separate premise of the trickle-down theory held that raising taxes on the rich eventually costs the government revenue by discouraging work. The latest economic research suggests that this is true — but only if you raise the top tax rate higher than (approximately) 70 percent.

Meanwhile, French economist Thomas Piketty has demonstrated that high tax rates reduce pre-tax inequality – ostensibly, by discouraging rent-seeking among top executives, whose compensation is often determined less by productivity than a combination of social mores and their own audacity: CEOs are less likely to extract an extra $5 million from their companies (instead of allowing their firms to invest that sum in other purposes) if they know that Uncle Sam will collect 70 percent of their bonus. Thus, there is now some reason to believe that confiscatory top rates can reduce wage inequality, while producing some gains in economic efficiency.

All of which is to say: In 1980, taxing incomes above $216,000 (or $658,213 in today’s dollars) at 70 percent was considered a moderate, mainstream idea, even though wage inequality was much less severe, and supply-side economics had yet to be discredited.

This week, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez told 60 Minutes that she believes the U.S. should consider taxing incomes above $10 million at a 70 percent rate. Specifically, the congresswoman suggested that taxing the rich at such a rate would be preferable to forgoing major investments in renewable energy, and other technologies necessary for averting catastrophic climate change.

And centrist pundits were scandalized by her extremism.

National Journal reporter Josh Kraushaar argued that, while congresswoman Rashida Tlaib’s profane call for Trump’s impeachment was getting more attention, Ocasio-Cortez “calling for a 70 percent tax rate on the nation’s most-watched news show a whole lot more politically damaging for Ds.”

As we’ve already established, there is nothing substantively extreme about Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal. It is true that, when the top marginal rate was last at 70 percent, there were more loopholes in the tax code enabling the affluent to sneak out of that top bracket. But this does not mean that Ocasio-Cortez’s tax policy would actually be more radical than Jimmy Carter’s was – after all, the congresswoman’s 70 percent rate kicks in at a much higher threshold, exclusively targeting America’s super-rich (who weren’t nearly as well off in the 1970s as they are now). One can raise a variety of technocratic quibbles with Ocasio-Cortez’s plan (raising taxes on capital gains might be a more effective way of soaking the super-rich; a confiscatory top marginal rate might prove impotent absent a global war on tax havens). But it would not be extreme in its redistributive implications, relative to our country’s past tax practices, or to other nations’ current ones. And a significant number of highly respected economists have endorsed top tax rates roughly as high as the one floated by the congresswoman, while Piketty has advocated for an 80 percent top rate.

Meanwhile, in terms of public opinion, Ocasio-Cortez’s view on tax policy for the rich is much more mainstream than Susan Collins’s.

Last year, a Data For Progress and YouGov Blue poll asked voters if they would support a 90 percent tax rate on all income above $1 million. Respondents opposed the idea by (just) a two-point margin. In Pew Research polling taken shortly before Congress passed the Trump tax cuts, voters opposed cutting taxes on households that earn more than $250,000 by a 48-point margin.

The notion that confiscatory tax rates on super-high incomes are more popular than the Republican Party’s alternative is buttressed by other data. For example, when Berkley political scientists David Broockman and Douglas Ahler offered voters seven different tax-policy options (ranging from extremely conservative to extremely progressive) in 2014, they found that the furthest left option — establishing a maximum annual income of $1 million (by taxing all income above that at 100 percent) — was the third-most-common choice, boasting four times more support than the Republican Party’s 2012 platform on taxation.

And yet, the fact that Susan Collins voted to sharply cut taxes on the rich in 2017 has not led nonpartisan news outlets to describe her as a far-right extremist. In fact, just yesterday, the New York Times referred to her as one of the Senate’s “most moderate members.” (Which is enough to make one wonder whether the overrepresentation of the affluent among national reporters — and the extremely rich, among owners of national media companies — might bias our political discourse in the upper class’s favor.)

All this said, it is conceivable that Kraushaar is correct; advocating for a 70 percent top tax rate could plausibly have political downsides for Democrats. But when journalists respond to Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal by declaring it self-evidently extreme and unpopular — instead of explaining who would be affected by the policy, and what effects economists believe it would have — they are creating such downsides, not neutrally reporting on them.