As Democrats in Washington wrangle over the extent to which they support progressive agenda items like Medicare for All and the Green New Deal, and as a left-leaning 2020 presidential field is steadily shaped, it’s easy for veteran observers of the Donkey Party to feel a bit disoriented. After all, in presidential nominating contest after contest dating back to 1972, self-identified Democratic progressives have been regularly outmaneuvered by party “moderates.” And there were plausible reasons that kept happening, beginning with an electorate in which conservatives significantly outnumbered liberals, and moderate “swing voters” offered Democrats the only path to a majority.

By the end of the Obama presidency and its horrible sequel, however, Democrats had reason to feel cheated by this long history of ideological self-restraint, which left them weakened at nearly every level of government, awash in corporate power and economic inequality, and still fighting to maintain the achievements of the long-ago New Deal and Great Society eras while battling a new wave of racism and sexism.

The eternal rationale of Democratic moderates based on their superior electability hit rock bottom with Hillary Clinton’s disastrous general election campaign, and did not gain much traction from a successful 2018 midterm cycle in which voters did not seem to care what kind of specific ideology Democratic candidates professed. Looking ahead to the next era of Democratic governance, progressives make sense in arguing that a more clearly left-bent Democratic Party wouldn’t lose significant numbers of votes for being too “socialist,” but would have a mandate for accomplishing a lot more than did the mixed and tentative records of the Clinton and Obama administrations.

I say all this as someone with impeccable moderate credentials of my own as former policy director of the Democratic Leadership Council. There are still, I believe, substantive grounds for, say, preferring a public-private health care system linked to an aggressive strategy for fighting provider cartels, as opposed to a single-payer system, or for envisioning the future economy in democratic capitalist rather than socialist terms. But the empirical electoral case for “moderation” has never been weaker, and moreover, the tendency of moderates to compromise on principles rather than simply means of implementing common progressive goals has been demonstrated too many times to dispute.

So at this particular moment, who needs moderate Democrats? At FiveThirtyEight, Perry Bacon Jr. establishes pretty clearly that there is no coherent “moderate” faction of rank-and-file Democrats who can stake a claim to the presidency in 2020.

Most polls don’t release detailed breakdowns of Democrats who identify as moderate and conservative, so it’s a bit hard to describe this group and its views precisely. But I reached out to the Pew Research Center to get details on the 54 percent of Democrats over all who identified as moderate or conservative, based on an aggregation of their surveys in 2018, and nonliberal Democrats appear to be made up of four main groups:

1. White voters without college degrees (30 percent).

2. Black voters (22 percent).

3. Latino voters (21 percent).

4. White voters with college degrees (16 percent).

I think this will be a complicated bloc to unify around a single candidate.

In the past, white southern moderate politicians (famously Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton) showed themselves capable of putting together coalitions that included non-college-educated white voters in the South and border states along with African-Americans from a similar religio-cultural background. That type of politician barely even exists today. African-American and Latino voters are beginning to gravitate toward presidential candidacies from their own communities, which may be more self-consciously progressive.

More subtly, we may be entering an era in which instead of Democratic progressives casting their lots with competing moderates of somewhat different dispositions (you saw a lot of that in 2008 when lefty activists split between Barack Obama and John Edwards), Democratic moderates split between competing progressives. I am impressed at how many of my own moderate Democratic acquaintances are attracted to Elizabeth Warren as a counterweight to Bernie Sanders.

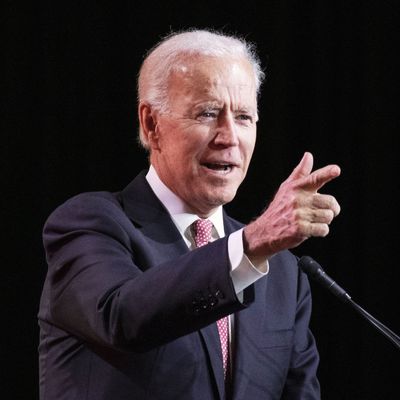

But all these trends cut across the currently immovable presence of the one 2020 candidate who will almost automatically appeal to Democratic moderates: Joe Biden. Bacon notes his unique nature:

[I]n a primary field where the other top candidates (Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren, in particular) are running hard to the left on equality issues and economic issues, Biden is positioned to appeal to the center-left in both spheres. He has a ton of relationships with black and Latino activists and powerbrokers from his time in the Senate and as vice president under Obama. He talks about his Catholic faith consistently, and at times he has taken conservative stands on abortion rights. He comes from a state (Delaware) that is traditionally Democratic but not particularly progressive, so he might appeal to white working-class Democrats not that thrilled about the party’s more left-wing candidates.

Perhaps even more obviously, Biden is a living link to the whole era of moderate-dominated Democratic politics, even as it passes from the scene, with particular appeal to low-information voters who have nothing but pride and affection for Barack Obama and Bill Clinton. And he won’t have to spend a minute building his name ID.

Biden’s also very old and has tons of baggage that opponents and the media will gleefully and redundantly exploit. And he might not choose to run at all.

There’s no obvious substitute for Biden as someone who appeals to moderates, as Bacon points out:

Other candidates could appeal to this group too, but pundits usually tout the wrong sorts of candidates for the wrong reasons — i.e. white, big-city, college-educated pundits may be overhyping Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota as a candidate who can appeal to all moderate voters because Klobuchar kind of embodies the white, educated, moderate political style of many of these pundits. A successful candidate for the moderates in the Democratic Party needs to win over black and Latino moderates — who are nearly half of this bloc — and can’t just be a spokesperson for Never-Trump-Republicans-turned-Democrats.

And age and ideology aside, there’s a question as to whether any moderate, Biden included, will alienate Democratic voters with the sort of reflexively “civil” rhetoric that sounds too much like surrender. Jamelle Bouie accuses Biden of this anachronistic habit:

For Biden, you don’t need to demonize the richest Americans or their Republican supporters to reduce income inequality; you can find a mutually beneficial solution….

[T]his is a faulty view of how progress happens. Struggle against the powerful, not accommodation of their interests, is how Americans produced the conditions for its greatest social accomplishments like the creation of the welfare state and the toppling of Jim Crow.

In an atmosphere of passionate and increasingly successful resistance to Donald Trump and the radicalized GOP he leads, “moderate” politics may just seem inadequate to the moment (as Barry Goldwater wryly put it in the last half of his famous quote involving extremism: “Moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue”).

It’s still possible that Biden (or Klobuchar, or Hickenlooper, or even the ultra-irenic Cory Booker) can build a primary and then a general election coalition based on the broadest possible anti-Trump alliance, recognizing that this sort of coalition may fall apart in the very moment of victory. More likely, the party of passionate progressivism will rise or fall with an agenda and a message that reverses the course of public policy decisively once and for all. And Democratic moderates will go right along.