As one might expect from a presidential field as large as the one Democrats are assembling for 2020, there are a variety of approaches to developing, rolling out, and talking about policy proposals. Indeed, given the natural obsession Democrats have about electability in the wake of Hillary Clinton’s shocking loss to Donald Trump in 2016, there’s been quite a bit of buzz about candidates’ policies — or the lack thereof — early in the current cycle.

But there are different ways in which precision or vagueness on policies — and in the latter case, which and how many policies are articulated — are utilized, depending on a particular candidate’s proclivities, identity, and strategic needs. Here are a few variations:

1. Policy As an Ideological Marker. In 2020, as in 2016, Bernie Sanders has been masterful in using a few high-profile specific policy proposals to undergird his self-presentation as a fearless challenger of corporate power and Establishment politics. His relentless advocacy of single-payer health care, tuition-free college, and a high minimum wage have also given him an indirect way to suggest that other Democratic candidates (in 2016 Hillary Clinton, and this year multiple rivals) aren’t so fearless or so independent of unsavory influences. This year he’s added a distinctive foreign-policy viewpoint that doesn’t sound like conventional Democratic rhetoric and helps maintain his credibility as the leading progressive in American politics.

It’s a mark of Sanders’s effectiveness that others in the 2020 field (including fellow senators Cory Booker, Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris, and Elizabeth Warren) have found it convenient to lend their support to his Medicare for All proposal in order to prove their own progressive bona fides. And it can work the other way, too: Putative “moderate” candidates Amy Klobuchar and John Hickenlooper have made their own unwillingness to go full single-payer their own ideological marker. Down the campaign trail it’s entirely possible that even nuanced differences on other highly symbolic policy proposals like the Green New Deal will carry a lot of implied ideological freight.

2. Policy As Signature. Candidates often roll out a particular policy as a sort of signature of their seriousness, or to identify them with voters concerned about a specific problem. Harris has done that twice: with an early progressive tax proposal, and with a more recent plan to boost teacher pay nationally. Booker’s “baby bonds” proposal is his distinctive approach to fighting income inequality and promoting racial justice. Klobuchar has sought to reinforce her image as a Midwesterner trying to rebuild that economically battered region with an infrastructure investment plan.

And then there are candidates who build their campaigns around a single issue, notably Jay Inslee, who is making climate change his sole preoccupation, and Eric Swalwell, who is doing the same with gun control (if he chooses to run after all, Michael Bloomberg would probably focus his mammoth bankroll on both those issues. And as time goes by, we will see struggling candidates try to reboot their campaigns with “bold” new policy initiatives that cover untrod ground.

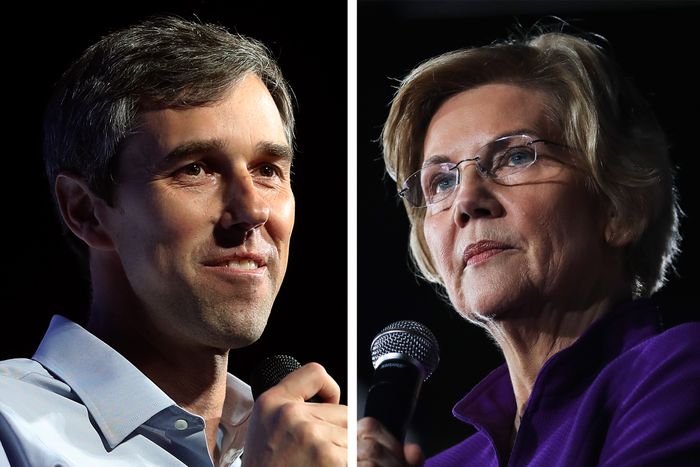

3. The Hazy Policy Option: Never Having to Tell Voters You’re Sorry. Presidential candidates running on their personalities, their charisma, or their biographies have long realized that getting down and dirty on policy specifics can alienate potential supporters without necessarily adding much to their appeal. That seems to be the approach being taken so far by two 2020 prospects, Beto O’Rourke and Pete Buttigieg.

Other than both being white men with a particular appeal to younger voters, the two candidates come across quite differently. O’Rourke actually has embraced a lot of specific policies (he was, after all, a three-term House member), but doesn’t talk about them much on the campaign trail, where he emphasizes his empathy for the challenges facing citizens and his eagerness to learn from them, as Politico noted last month:

“I’m going to make the rare admission for a politician that I don’t have a good answer to your question,” O’Rourke said at a recent campaign stop when asked what he would do to help in-home child care providers.

Directing an aide to collect the questioner’s telephone number, O’Rourke said, “Let me learn from you and not try to pretend that I have the answer.”

The exchange was reminiscent of O’Rourke’s first day as a presidential candidate, when he told a crowd: “I am all ears right now. There’s no sense in campaigning if you already know every single answer, if you’re not willing to listen to those whom you wish to serve.”

Some of Beto’s admirers with experience in the Obama administration remind us that the 44th president also dealt with a lot of concerns about policy vagueness in the early days of his 2008 campaign. Whatever its origin, the habit of emphasizing values and broad goals rather than policy specifics helped Obama, and may help O’Rourke, develop support across the usual intraparty ideological lines. That, too, may be one motive for Pete Buttigieg’s lack of focus on detailed policies, though he has been very clear in his belief that voters want compelling “narratives” more than just policy white papers, as Alexander Burns has observed:

Other candidates have anchored their candidacies in ideological or social causes, like Senator Elizabeth Warren’s opposition to corporate power or Senator Cory Booker’s concern for racial justice.

Mr. Buttigieg’s distinctive political passion appears to be storytelling, wrapping conventional liberalism in an earnest, youthful persona that Democrats might see as capable of winning over the middle of the country.

Whereas O’Rourke risks giving the impression he’s a lightweight, Buttigieg, with his knowledge of multiple languages and his habit of quoting James Joyce, sometimes seems too cerebral for politics. Being a bit hazy can be complicated, though it does increase strategic flexibility.

4. Policy As Identity. Elizabeth Warren has very deliberately gone about establishing herself as the most policy-intensive candidate in the 2020 field, with detailed proposals on issues ranging from agriculture and technology to banking, public lands, and child care. She’s in effect doubling down on her identity as a brilliant former college professor who could be the perfect antidote to four years of a president who doesn’t read, doesn’t think deeply, and doesn’t bother with facts or logic or arithmetic.

Some observers think this is a mistake insofar as sexist perceptions of Warren as a hectoring schoolmarm is her chief political problem. And there’s even a risk that her tendency to churn out specific policy plans aimed at specific constituencies (e.g., the agribusiness proposal she rolled out in Iowa) could come across as pandering.

On the other hand, Harris is building an impressively coherent agenda around a common core of ideas, mostly involving aggressive efforts to bust up oligarchical corporate structures and monopolistic consolidations. It’s an approach that could wear well on voters and media alike, if she’s not written off early as too substantive for American politics or too female to take on the atavistic warlord in the White House.

And speaking of Donald Trump, he may not be quite as able to shrug off policy matters as he was in 2016, as Elana Schor recently noted:

“In 2016, we were boxing against Jell-O,” recalled Jesse Ferguson, a veteran Democratic strategist who also worked on the Clinton campaign. “Donald Trump would say he agreed with anything or disagreed with anything, without regard to what he believed or what he’d said the day prior….”

But in 2020, Ferguson said, Democrats can contrast their plans with “what he has actually tried to do as president. He can’t run away from his own policy agenda anymore because he’s actually tried to enact it.”

If Democrats let the objective realities of the Trump presidency guide their policy pronouncements, they should do well.