On questions of immigration policy, Democrats know what they’re against. The party has said, in no uncertain terms, that building medieval walls, closing the southern border to all legal commerce, withdrawing aid from Central American governments, deploying thousands of U.S. troops to southern Texas, and separating migrant children from their parents (and then subjecting them to physically and psychologically torturous conditions, before losing them in foster care) are not wise approaches to policing America’s borders.

But Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, and Team Blue’s small army of 2020 candidates appear far less certain about precisely what a wise (or just) alternative would look like.

Granted, Democrats have a consensus position on immigration: the classic, formerly bipartisan pairing of a pathway to citizenship for the law-abiding undocumented people already among us, and border militarization to keep future, aspiring undocumented immigrants out. But invoking “comprehensive immigration reform” does little to clarify the party’s views on precisely how our government should be handling the recent influx of Central American asylum seekers. We know Democrats don’t want to deter such migrants by separating their families. But do they want the government to put such families in long-term detention (together) so that they don’t abscond into the interior of the country before their asylum hearings — as the Obama administration did in 2014? Or do they want to let those families await their days in court outside of confinement, and then simply deport those who fail to show up for their hearings by conducting massive, nationwide ICE raids — as the Obama administration did in 2016?

We know that the Democratic leadership doesn’t want to abolish ICE. But they do often evince a moral objection to discrete instances of (routine) internal immigration enforcement like workplace raids. Even the party’s opposition to border walls is shot through with ambiguity. At times, the objection is framed as an ideological opposition to border militarization itself, as when Kamala Harris argues, “the strength of our union has never been found in the walls we build; it’s in our diversity and our unity and that is our power.” But other times, the complaint is merely technocratic — suggesting Democrats share Trump’s belief in the vital importance of enhancing border security, but dispute the efficacy of his tactics — as when House Appropriations Committee chairwoman Nita Lowey said, “Smart border security is not overly reliant on physical barriers, which the Trump administration has failed to demonstrate are cost-effective compared to better technology and more personnel.”

This incoherence has made it easy for the far-right to paint Democrats as supporters of open borders; the center to portray them as political cowards whose refusal to enforce the border (i.e., sanction the level of state violence necessary to prevent human beings in South America from seeking a better life for their families in the wealthiest country on Earth) is clearing the way for fascist rule; and the left to deride Democrats as hypocrites who are happy to leverage the public’s visceral disgust with the realities of immigration enforcement, but have no real interest in fundamentally changing those realities.

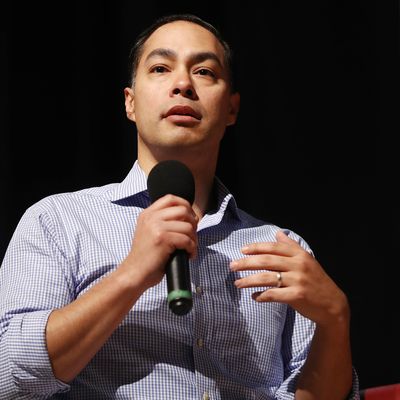

But on Monday, Julián Castro offered a compelling rebuttal to that last critique. Castro’s rivals for the Democrats’ 2020 nomination have released detailed plans on a wide range of issues, from health care to corporate concentration to wage stagnation to climate change. But as of this writing, Castro is the only one who has attempted to match his party’s progressive rhetoric on immigration to a detailed, concrete policy vision.

In a Medium post outlining his agenda, Castro makes the moral sentiment behind so much Democratic rhetoric on immigration explicit — that humanism must take precedence over nationalism. “When we see families seeking refuge, we don’t see criminals, or an invasion, or a threat to national security,” Castro writes. “We see kids. We see parents. We see people. We see people first. Because we are people first. And it’s time for an immigration policy that puts people first.”

Castro endorses a laundry list of consensus Democratic positions (pathway to citizenship for the 11 million undocumented, restoring pre-Trump levels of refugee admissions, protecting Dreamers and TPS recipients). But he then breaks with his party’s orthodoxy on the necessity of increasing border enforcement. Under Castro’s plan:

• Entering the United States without papers would be a civil infraction, instead of a criminal one.

• Customs and Border Enforcement would focus on policing the border, rather than engaging in internal immigration enforcement (as it currently has wide latitude to do).

• Immigration detention would be a rarity, deployed only when a the government has good reason to suspect a given undocumented person is a threat to the public’s safety or well-being.

• Immigration courts would gain independence from the Justice Department. (At present, the attorney general has the authority to set precedent for immigration judges, a power that former Attorney General Jeff Sessions made full use of).

• Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) would have its mission redefined. ICE would retain its “national security functions such as human and drug trafficking and anti-terrorism investigations” — while its immigration enforcement operations would be reassigned to other law enforcement agencies. Castro told Vox that he believes this “would prioritize individuals with serious criminal convictions, threats to national security, and multiple reentries with a criminal history.”

Taken together, these proposals would transform immigration policy in the United States … by largely reinstating pre-9/11 norms of enforcement.

Technically, entering the U.S. illegally has been a criminal infraction since 1929. But the federal government did not start routinely prosecuting border crossers until the George W. Bush administration. Similarly, internal immigration enforcement was far more lax for most the 20th century than it has been since the onset of the (forever) war on terrorism.

In recent days, the Trump administration has taken to describing circumstances at the U.S. southern border as “a humanitarian crisis.” Castro’s plan spotlights how disingenuous that phrasing is by demonstrating that the inhumanity of the existing situation is a policy choice. Under the system he envisions, Central American asylum seekers — along with all undocumented immigrants apprehended by authorities — would be briefly detained, screened for “red flags,” assigned a case manager who would be charged with monitoring their whereabouts, and then released into the U.S. while awaiting an immigration hearing. Some would stay with relatives. Those seeking asylum would have access to well-funded, voluntary shelters and care services. The “humanitarian” crisis would be solved.

Of course, the crisis the White House actually cares about — the state’s failure to prevent the inflow of Central American undocumented immigrants — would remain unresolved.

Under Castro’s regime, if undocumented immigrants fail to show up for their legal hearings, they would then become subject to deportation. The former San Antonio mayor emphasizes this point, to make clear that he is not calling for “open borders.” And yet, with internal enforcement reduced — and the government’s resources concentrated on undocumented criminals — Central American migrants who abscond into the country would have a very good chance of avoiding deportation and establishing roots. In other words: The policy would prioritize minimizing the inhumane treatment of undocumented immigrants, over minimizing undocumented immigration.

Understandably, Castro does not wish to frame his policy in such terms. Rather, the candidate insists that by pairing a liberalized enforcement regime with generous aid to Northern Triangle countries — or, in his words, a “a 21st century Marshall Plan for Central America” — the U.S. could reduce illegal border crossings and the ill-treatment of the undocumented simultaneously. But the evidence for this proposition isn’t terribly strong.

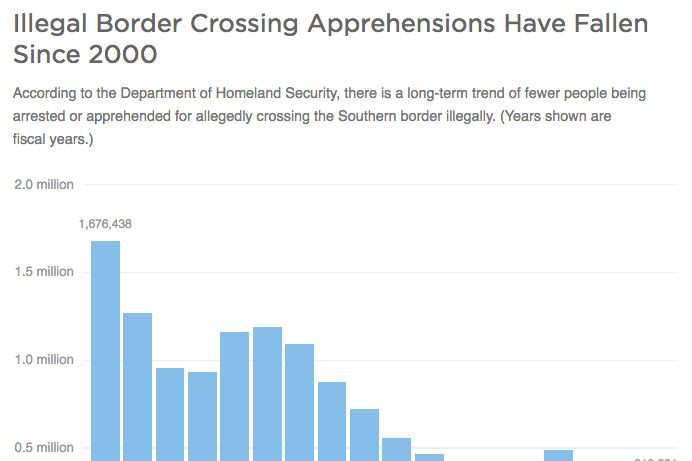

In my view, the substantive trade-offs inherent to Castro’s plan are worthwhile. Our government is deeply implicated in the dire conditions that Central Americans are fleeing. Our population is rapidly aging, and an influx of younger workers (even “low skill” ones) would have significant benefits for economic growth. Meanwhile, illegal border crossings have been declining for two decades, and are currently hovering near half-century lows. It seems likely that Castro’s policies would prompt an increase in undocumented migration. But it also seems likely that — for anyone who believes in the universal dignity of all human beings — the costs of that development would pale in comparison to those of our present system, which rains needless suffering down on migrant children and longtime, law-abiding U.S. residents.

Still, one needn’t be a restrictionist to wonder whether Castro’s plan might produce conditions that undermine the bargaining power of labor unions, and native-born workers at the bottom of the job market. And it’s also fair to ask whether he has grappled with the potential costs of humanely caring for any and all asylum seekers who arrive at our nation’s doorstep. As Vox’s Dara Lind writes:

[T]he biggest question mark in Castro’s proposal — and one that the Democratic field is likely to struggle with as a whole — is the immediate crisis facing the US right now: the influx of up to 100,000 unauthorized immigrants, many of them families, children, or asylum seekers, into the US a month, and the challenges of caring for them … People will continue to come — perhaps even in unprecedentedly high numbers. Even the short-term proposals to deal with migrants who are already here will take time to build up.

And there’s nothing in this proposal to directly address the large number of people who won’t ultimately qualify for asylum under US law — even if they have attorneys, and even if the Trump administration efforts to restrict asylum for, say, victims of gang and domestic violence are reversed. Not everyone fleeing their home country out of legitimate need qualifies for asylum as US law defines it, and many of the people currently coming will not.

To many migration experts — not just immigration hawks — the “mixed flow” into the US is a problem. They believe it is important to reduce the number of people coming to the US without legitimate asylum claims, both because it frees up resources to address the remaining asylum seekers and because it reduces the possibility of deliberate malfeasance or fraud.

The biggest problem with Castro’s vision, however, may be less substantive than political. The Democratic Party’s views on immigration enforcement tend to be incoherent and contradictory for a reason — the general public’s are, too. In recent polling, roughly 80 percent of Americans — including a majority of Republicans — say that all undocumented immigrants who pass a criminal background check should be given a path to legal status. And yet, a majority of American voters also support ICE’s efforts to enforce immigration law in the American interior. Which is to say: They ostensibly believe that law-abiding undocumented residents should have the right to live here legally — but until 60 senators come around to that position, ICE agents should go around arresting and deporting any random undocumented immigrants they happen to come across.

Similarly, while the public recoils from the cruelty of Trump’s border policies, it also supports “better border security and stronger enforcement,” while opposing “basically open borders” (whatever that means). It’s likely that some voters take their cues from partisan elites on border security, and thus, would adopt a more dovish position if the Democratic leadership did. But the Democratic coalition is home to a significant number of voters with conservative views on immigration and liberal ones on economics. And such voters are overrepresented in Electoral College swing states, and in the House and Senate. Given these facts, it isn’t too surprising that none of the Democrats’ 2020 front-runners — including self-avowed socialist Bernie Sanders — has loudly called for decriminalizing illegal border crossings, and relaxing internal enforcement. Nevertheless, Castro’s proposal is a worthy contribution to the 2020 debate.

Judging by current polling, the former Housing secretary isn’t going to be a true contender for the Democratic nomination. But his policies could provide the next administration with a framework for progressively reforming immigration enforcement, especially since many of them can be implemented (quietly) through executive action.