The “Biden bounce” — an impressive and surprising surge of support for the former veep in multiple national polls in the wake of his formal announcement of candidacy — was all the buzz in political circles yesterday. But the residual question is whether it can last or, better yet for Biden, flower into something like an unassailable lead over his gigantic field of rivals.

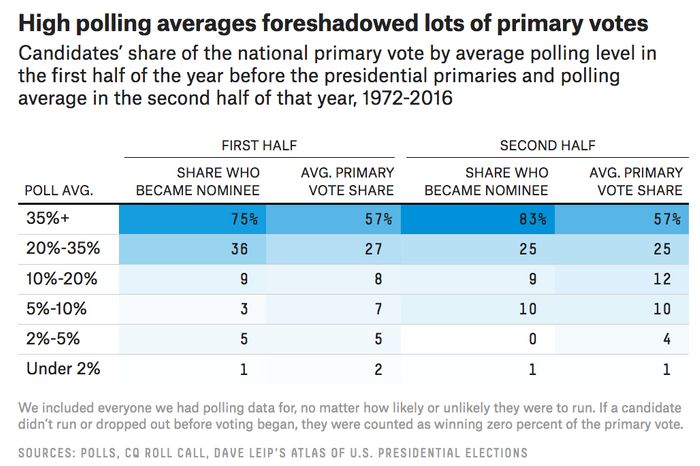

Now there’s a common species of Twitter scold who becomes furious at the very question on the grounds that “horse-race polls” so far in advance of elections are “meaningless,” and that writing about them is what’s wrong with American politics and media blah blah bark bark woof woof. As it happens, Geoffrey Skelley recently went through the process of looking at early-nomination-contest polling dating back to 1972 (!), and discovered that such polls taken the year before a presidential election often have high predictive value. That’s particularly true for strong early front-runners.

Biden’s latest national poll standings (ranging from the mid-to-high 30s) is in the area that is correlated with eventual victory in a majority of cases. Since some of his “bounce” is probably temporary (nearly all major candidates get some sort of post-launch bounce), it is probably more accurate to say Biden is on the borderline between being a strong favorite to win the nomination and just a good-but-hardly-safe bet.

But if you examine the recent history of nomination contests, you quickly discover a phenomenon that is easy to miss if you only focus on early polls and final results: Early front-runners often go through a swoon in popularity, or even a political near-death experience, somewhere along the way. And some don’t survive at all.

Consider these examples:

* In early 1979, Ronald Reagan was about where Biden is today in the polls, albeit with more deeply entrenched support, given his long service to the conservative movement and his strong challenge to incumbent President Gerald Ford in 1976. Reagan lost the Iowa caucuses to George H.W. Bush in an upset, and appeared to be in trouble until he beat Poppy in New Hampshire after running a strongly ideological campaign there.

* In early 1983, Fritz Mondale — another former vice-president — was also registering poll numbers similar to Biden’s. And his polling grew stronger later in 2003. He eventually won the nomination, but not until Gary Hart threw him off track by winning New Hampshire and five other early primaries.

* In the 1988 Democratic nomination contest, Gary Hart was in the mid-30s in early 1987 polls, before imploding entirely and dropping out of the race in May when an extramarital dalliance was revealed (he eventually reentered the contest, but was not a serious factor).

* In the 1988 Republican nomination contest, Poppy Bush was in the high 30s in the polls in the first half of 1987, and got stronger later that year. But then he finished third in Iowa, trailing both Bob Dole and Pat Robertson, before beating Dole in New Hampshire by hammering away at Dole’s refusal to take a “no tax increase” pledge (which Bush did, to his eventual regret years later).

* In 1996, Dole was the heavy Republican front-runner early on, averaging well over 40 percent in 1987 polls. But he again lost New Hampshire (this time to Pat Buchanan) and then lost to Steve Forbes in Delaware and Arizona before righting the ship.

* Throughout 1999, George W. Bush was crushing his rivals in the polls, registering over 60 percent in the second half of that year. He stumbled in New Hampshire against John McCain before recovering via a scorched-earth negative campaign against McCain in South Carolina.

* Hillary Clinton was polling in the high 30s in early 2007, and the low 40s later that year. She lost her mojo to Barack Obama in Iowa, of course, and needed to win her own upset in New Hampshire in order to survive to make the 2008 contest an extended slugfest.

* That same cycle, Rudy Giuliani was polling in the low 30s in the first half of 2007, and faded from sight steadily after voters started voting.

As you can see, there are extensive precedents for early front-runners hitting major bumps and then righting themselves — or having the wheels fall right off. What this suggests about Joe Biden is that his current standing, assuming it doesn’t decline right away, is meaningful, but he and we can count on bad things happening to him along the road to Milwaukee. Democrats’ current proportional delegate award system makes a front-runner’s margin for error lower than it was in the old days, when an Establishment favorite could fatten up on winner-take-all primaries against a divided field of challengers. If a contested-convention scenario actually materializes, the key question could be whether it’s Biden or someone else (Harris? Warren? Booker? O’Rourke?) who is the logical unity candidate.

More generally, Biden’s ability to handle the inevitable adversity he will face could matter a lot, particularly if he commits one of his famous gaffes or has something really damaging arise from his many decades in public office at about the same time a particular rival rises like a rocket to challenge him.

Strong early-nomination-contest polling is meaningful, but no guarantee of anything other than fond memories.