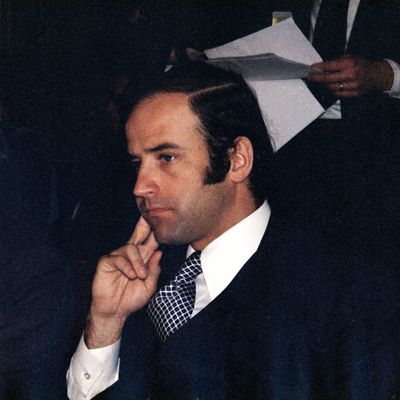

One of Joe Biden’s favorite campaign riffs underscores his belief in the value of civility and bipartisanship. Inevitably, Biden reminisces about his young Senatorial days when he would pal around (and occasionally cut deals) with segregationists. “I was in a caucus with James O. Eastland,” he said again last night, launching into his nostalgic riff about the good old days when senators could argue with each other but still compromise.

At first blush, Biden’s segregationist riff is disturbing. When you poke below the surface, it gets even more disturbing. It suggests that he has not grasped any of the tectonic changes in American politics, and that he is equipped neither for the campaign nor the presidency.

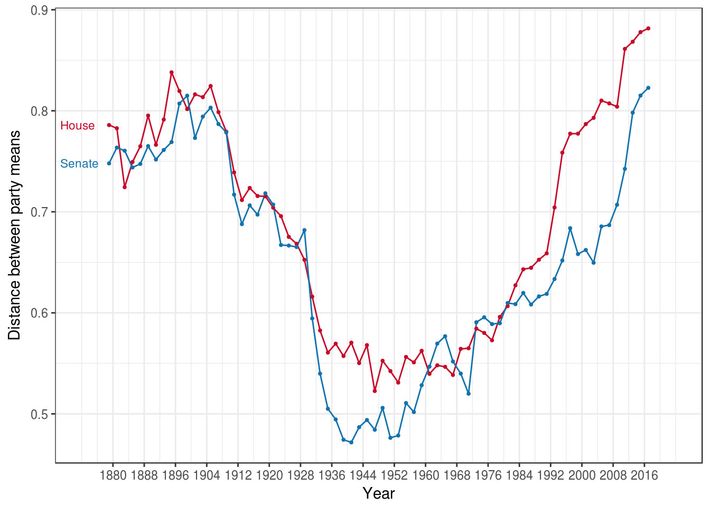

American politics has grown more polarized because the unusual and precarious conditions of the 20th century have disappeared. Politics in the 19th century was deeply polarized around the linked issues of issues of race and big government (we fought a Civil War, remember.) But after Reconstruction was crushed, the Republican Party abandoned its commitment to African-American equality and activist government, while the Democratic Party eventually adopted those identities. In the decades while the Republicans were moving right and the Democrats were moving left, there was a long period in which the parties overlapped. During that time, bipartisanship was the norm. Biden came of political age during the period when polarization had reached its historic nadir:

That’s the era Biden grew up in and recalls fondly. It has disappeared for reasons that may be lamentable, but are grounded in large, immutable forces of ideology and self-interest. Today’s partisan division reflects the same elemental conflicts between Yankee socially progressive advocates of energetic central government and Southern “strict constructionist” defenders of the existing social hierarchy that divided the political system of the 19th century.

What’s more, modern leaders have learned that the old conventional wisdom that voters would punish them for failing to get along is false. As Mitch McConnell has bluntly explained, persuadable voters do not pay close attention to policy details. If they see leaders in both parties getting along, they will assume things are going well, and — this is the crucial detail — they will consequently reward the party in power. If they see a nasty partisan fight, they will assume Washington is failing, and reward the opposition. To ask the opposing party to compromise with the majority party is to ask it to undermine its own political interest.

Biden either fails to grasp this dynamic, or believes he can overpower it with sheer charm. “Folks, I believe one of the things I’m pretty good at is bringing people together,” Biden boasted of his time as vice-president. “Every time we had a trouble in the administration, who got sent to the Hill to settle it? Me. No, not a joke. Because I demonstrate respect for them.”

This account of Biden’s role in the Obama administration is very different than what I observed. Biden did play an important role in wooing three Republican senators to support the stimulus bill in 2009, a crucial accomplishment and a necessity, given that Democrats had 58 Senate seats at the time and adamantly refused to disable the filibuster. However, those three Republicans faced such intense backlash from the right that one of them, Arlen Specter, was driven out of the party altogether, and the other two, Susan Collins and Olympia Snowe, subsequently refused to support any health-care bill on any terms. The aftermath of the success was such that it could never be repeated.

Afterward, Republicans held their wall of total obstruction throughout Obama’s terms. On some relatively small matters where bipartisanship was needed just to keep the lights on, Biden did often play a role in sealing negotiations with the GOP. My understanding at the time was that Biden’s interventions were a form of kabuki, allowing Republicans to avoid the spectacle of negotiating with the hated Alinsky-ite secret-Muslim atheist socialist president. In any case, while the Obama administration produced a lot of historic reforms, his negotiations (other than the unrepeatable case of the stimulus) did not yield any of them. Biden’s deals concerned small-bore stuff.

Biden’s nostalgia for the good old days of backslapping, and his conviction that it can be revived through interpersonal charm, is a durable Washington myth. But Biden’s habit of invoking his friendship with segregationists to illustrate it is particularly dense. For one thing, the example doesn’t actually support the point he’s trying to make. Biden is attempting to tout his ability to work across the aisle, but he’s citing friendships with members of his own party. And yes, as Biden often points out, he had important ideological and generational differences with the old segregationist Democrats of the Deep South. But the differences weren’t that profound — as Biden often points out, Delaware was a slave state, and its white population long retained the attitudes about race and criminal justice more in line with the South than the North. There were divides, but bridging divides within your own party is not actually a monumental achievement.

For another, by citing segregationists, he is revealing the very reason the bipartisanship he longs for can’t return. The era of bipartisanship was built on suppressing racial conflict. The white South could only be cajoled into a coalition that supported bigger government by preventing African Americans from voting and, at times, outright denying them the benefits of government altogether. He’s invoking the most unappealing aspect of the bipartisanship era. You can argue that forging American consensus was worth the cost of suppressing racial conflict, but actually highlighting the grotesque moral costs of that era is a bizarre way to advertise it.

The most inexplicable thing about the segregationism riff is that it calls attention to a subject Biden should be trying to avoid: his antiquated record on race. That record is not insurmountable. Biden can argue that he’s grown and learned, and as a transactional politician he and his party are now heavily reliant on black voters, who have the leverage to compel Biden to take account of their interests. Right now, Biden commands strong support among African-American voters. He may or may not be in danger of losing that support. But one way he might lose it would be, I don’t know, talking constantly about his friendships with segregationists.

The usual way arguments work is that you bring up the strongest case for your argument, and your opponents bring up the weakest case. If you’re a pacifist, you lean on the bad wars, and leave it up to the other side to talk about fighting Hitler. Biden is making the odd choice of highlighting his own weakest example. The auto-reductio-ad-absurdum is a signature Biden rhetorical move that helps explain why his previous two presidential campaigns crashed and burned.

The most favorable interpretation of Biden’s bipartisanship nostalgia is that he knows he’s peddling baloney, but he’s doing it because people like it. But that seems hard to square with him relying on an example that’s so politically radioactive. If Biden’s just being politically savvy, why is he doing it in such an un-savvy way?

The other, scarier interpretation is that Biden actually believes the nonsense he’s peddling. He’s a 76-year-old man, and maybe he shares the inability of many old people to surrender the lessons of their youth. The American political system of today does not resemble the one that fostered Biden’s rise. Biden is right to question the realism of the expansive demands of his party’s left. But if he truly believes he can lead the Democratic Party by restoring the bygone habits of the system that bred him, he is unqualified to lead either his party or his country in a transformed era.