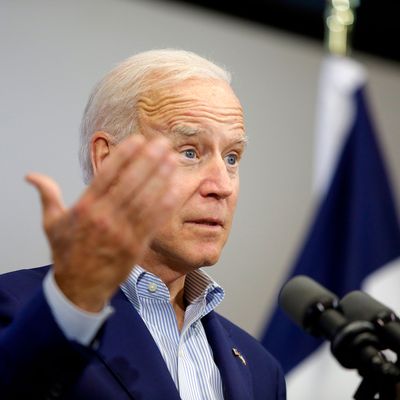

Earlier this week, results from a USC/Los Angeles Times survey were published showing a “generic Democratic nominee” created by more than 5,100 primary voters from both parties. Their mandate was simple: to combine the traits they believed would fare best in 2020 against President Donald Trump into a single prototypical candidate. The nominee they built maps mostly onto what early polls reflect: Seventy percent said that a man would fare best against Trump, and 68 percent said that a white candidate would. Fifty-six percent favored a white male, and 57 percent said that a moderate was more electable than a liberal or progressive. With the exception of ideal age — which respondents marked down as between 51 and 65 — these traits appear to explain, at least partially, the early polling lead enjoyed by Joe Biden.

But as my colleague Ed Kilgore noted, black respondents were less likely than either their white or Latino counterparts to endorse this prototype. They believed by a 56/39 margin that a black candidate would fare better than a white one — which somewhat complicates the argument for Biden’s “electability” that seems to fuel his polling edge among black voters. (According to an Economist/YouGov poll published last week, Biden was supported by 50 percent of black Democratic primary voters, with Bernie Sanders coming in second at 10 percent.) Perhaps the black respondents to the Times survey believed that an ideal black candidate would be the best match for Trump — just not the ones who are currently running, namely Kamala Harris and Cory Booker. Or maybe they felt the combination of traits Biden embodies was more important cumulatively than being black. Whatever the reason for the split, black Democrats remain the most bullish racial demographic when it comes to Biden’s chances. A Los Angeles Times report from last week features interviews with several about their support, fewer of whom cite Biden’s warm relationship with his former boss, Barack Obama, than their assessment that he is best equipped to navigate a racist and misogynistic electorate to oust Trump.

Whether this assessment survives the debates is yet to be seen. But the takeaway is clear: Biden has a built-in advantage among black Democrats that both contradicts their preferred candidate profile and has been mercifully immune to his past as an anti-busing advocate and architect of mass incarceration. Given the importance of black voters to any Democratic candidate’s chances at victory — especially in the early primary state of South Carolina — this is a major boon for the former vice-president. It also means that black voters have been instrumental in keeping Biden’s 2020 hopes afloat despite his willingness to risk torpedoing their relationship.

One would think that Biden could make the case for his prowess at facilitating bipartisan consensus without bragging about his willingness to work with segregationists in his own party. He seems to think otherwise: “I was in a caucus with [fellow Democrat and former Mississippi senator] James O. Eastland,” Biden said at a fundraiser in New York City on Tuesday. “He never called me ‘boy,’ he always called me ‘son.’” It is unclear why a bigot like Eastman declining to call Biden “boy” would reflect well on their relationship. “Boy” was a slur to degrade black men. Biden is white. The former vice-president continued: “Well guess what? At least there was some civility. We got things done. We didn’t agree on much of anything. We got things done. We got it finished. But today you look at the other side and you’re the enemy. Not the opposition, the enemy. We don’t talk to each other anymore.”

Biden was promptly criticized for his remarks by his black primary opponents, Harris and Booker. But when asked if he should heed Booker’s advice and apologize, Biden was obstinate. “Apologize for what?” he said. “Cory should apologize. He knows better. There’s not a racist bone in my body. I’ve been involved in civil rights my whole career, period, period, period.” Biden’s record is mixed on this front: He was a consistent voice in the U.S. Senate in support of expanded voting rights, affirmative action, and working to end employment discrimination. But as my colleague Eric Levitz has documented, he also co-authored the 1994 Clinton crime bill — which made federal death penalty statutes harsher, eliminated opportunities for inmates to pursue higher education, and made available more funding for police and prisons — and spoke out against busing in Delaware as a way to integrate schools. He has a history of making racist remarks, including when he described his future boss, then-candidate Obama, as “the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy” to run for president. Biden was also close to other segregationists in the Senate on a personal level. He enjoyed a warm relationship with Strom Thurmond, whom he called “the consummate public servant.” (Thurmond is famous for his record-setting filibuster of the Civil Rights Act of 1957.)

It remains unclear if Biden’s support among black voters is actually made precarious by such cavalier behavior, or if the presumption of his electability makes him immune to their potential fallout. But given the seeming incongruity of black voters’ early support, he is playing with fire. At the very least, his behavior conveys ingratitude: Flaunting his willingness to work with James Eastland and former Georgia senator Herman Talmadge — both of whom believed black people to occupy a subordinate class of human being — is, at the very least, disrespectful for a man so reliant on black support. But in a way, he is exploiting a timeworn dynamic. Black voters often back Democratic candidates who do not reflect their values — and sometimes actively harm their communities — in part because they know the alternative is worse. Black Virginians were forgiving of Governor Ralph Northam’s blackface debacle earlier this year. They also knew that if he was ousted, the spectre of Republican control would grow. Perhaps black Democrats will continue to buoy Biden’s candidacy in a similar fashion, and chart an easy path for him through the primary. But that assumes the resilience of a dynamic that the former vice-president insists on flaunting: that black voters will not waver in supporting the candidate they think they need, rather than a candidate they want.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly attributed two statements to James O. Eastland. The remarks in question were distributed in a leaflet at a rally where he was speaking but were erroneously attributed to Eastland in a 2002 book. We apologize for the error.