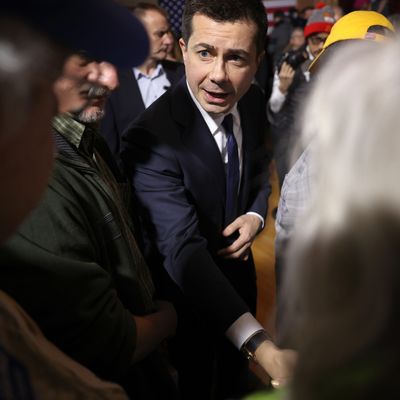

On Wednesday, the former mayor of Indiana’s fourth-largest city argued that he is uniquely qualified to be president because he grew up in a state that has no ocean beaches.

“In the face of unprecedented challenges, we need a president whose vision was shaped by the American heartland rather than the ineffective Washington politics we’ve come to know and expect,” Pete Buttigieg explained to his Twitter followers.

Many Democrats found this argument unpersuasive. More specifically, progressives suggested that Buttigieg’s reverential invocation of the heartland was a racial dog whistle. After all, the term refers to the portion of the United States that does not touch any ocean, a region that, while vast and heterogenous, is decidedly more white than America’s major coastal cities.

On Thursday, Buttigieg assured voters that he did not intend to suggest that America needed a president whose “vision” was shaped by the uniquely virtuous culture of midwestern white people. Rather, he was merely saying that America needed a president whose “vision” was shaped by the uniquely virtuous culture of all people who live in states that lack major seaports.

Regardless of whether one considers paeans to the “heartland” to be inherently racist, it seems indisputable that they are inherently stupid. As the Atlantic’s Ben Zimmer notes, the concept was initially a geostrategic one:

The British geographer Halford Mackinder used “The Heartland” to refer to the interior of the interlocking continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa, a landmass he called “the World-Island.” Eastern Europe held the key to control of the “Heartland” and in turn the “World-Island,” Mackinder argued in his 1919 book, Democratic Ideals and Reality. As the European powers clashed in World War II, American commentators seized on Mackinder’s model, looking inward to find the equivalent North American “Heartland.” The first mentions of an American “heartland” in newspaper databases appeared in 1943 — the same year a more outward-looking geopolitical expression, globalism, also took hold. Indeed, the early appeals to the nation’s “heartland” can be thought of as a cozy, reassuring domestic reaction to the “globalist” anxieties of the day.

In the June 1943 issue of Harper’s magazine, Bernard De Voto wrote in his column “The Easy Chair” about how Middle America was largely indifferent to the wartime preoccupations of the coastal elites. De Voto rejected the label provincialism, writing, “It is not that the Middle West is provincial but, first, that it is the American heartland, and second that it has developed an organic local life. The heart of the continental nation, it is so deep in distance and feels so secure that an instinctive disbelief is central in its consciousness.”

While De Voto fretted about the heartland’s lack of engagement with international issues, he praised the region’s potential for “comfort, kindliness, fellowship, human sympathy, [and] hope.” Those would come to be recognized as “heartland” values[.]

Anyhow, the idea that the myriad towns and cities scattered across the American interior all share a distinct set of values — let alone hold a monopoly on “human sympathy” and “hope” — never made much sense. But ever since the advent of the internet (or commercial air flight, or interstate highways), it’s been patently absurd. America may not have a monoculture in 2020, but on the list of identiarian categories that meaningfully divide us, “coastal versus interior dwelling” ranks quite low. There are meaningful geographic divides in U.S. politics, but they lie much more along lines of density than region. People living in rural parts of California tend to be more politically simpatico with people in rural Oklahoma than with the median San Franciscan. Meanwhile, people in Buttigieg’s hometown of South Bend, Indiana, tend to vote more like Brooklynites than like their fellow Hoosiers in the exurbs of Indianapolis.

Nevertheless, the “heartland” has remained a staple of American political rhetoric, ostensibly because Republicans see it as a useful fiction to invoke when explaining why it is actually good that America’s electoral institutions grossly underrepresent people who live in (left-leaning) coastal states, while Democrats see paeans to the concept a handy means of distancing themselves from their geographic base of support (which is something they are perennially eager to do because America’s electoral institutions grossly underrepresent left-leaning coastal states).

Pete Buttigieg’s bad tweet about the heartland is illustrative of the latter reality. The 2020 general election is likely going to be won and lost in the “heartland” state of Wisconsin. And the 2020 Democratic primary is going to be profoundly shaped by the preferences of people who live in the “heartland” state of Iowa. So, if the “heartland” is actually a real thing that meaningfully exists, then Pete’s formative years in the “heartland” state of Indiana would give him a leg up on the competition.

But whatever short-term instrumental value the concept has to Pete Buttigieg — or to a Democratic Party looking to expand its appeal in the parts of the country that pack more power per vote — it’s a counterproductive idea for liberals to affirm in the long run. Every in-group identity implicitly defines itself in opposition to an out-group. And progressives do not want people who live in landlocked states defining themselves in opposition to coastal cities (a.k.a., the Democratic base). It would be far better for the party if voters in Rust Belt regions identified politically as members of the “99 percent.” In the face of unprecedented challenges, Democrats need a nominee whose vision was shaped by the American working class rather than the ineffective billionaire politics we’ve come to know and expect.

All right, that would also be a bad tweet. But it’s a bit less bad than Pete’s.