The dream of a “V-shaped recovery” died Thursday of complications from coronavirus.

For months, Wall Street’s optimists have been betting that America’s bedridden economy would bolt upright as soon as the pandemic had passed: After all, the private sector had a clean bill of health before catching COVID-19. Months ago, America’s unemployment rate was near half-century lows, and analysts were expecting a “phase one” trade deal with China to further boost GDP growth. Today, the economy’s fundamentals remain sound; the fault is in our stars, not our financial system. Thus, once all epidemiological constraints are lifted, pent-up demand will be unleashed — and growth will rise as rapidly as it fell in March, painting a “V” across economists’ charts.

This scenario was always less likely than the bulls wanted it to be. True, the global economy had enjoyed a “V-shaped” recovery after the SARS outbreak in 2003. But SARS did not force most of the global economy to take a weeks-long hiatus. Even if Congress’s fiscal response had been flawless — which is to say, even if we gave every previously viable business the funds that it needed to weather the storm — widespread firm failures would still be inevitable. This is because the scale of the coronavirus shock was bound to foment (or accelerate) structural changes in commerce and consumption. Many movie theaters that were narrowly profitable in the pre-COVID world will not be in the post-COVID one. Now that every major firm in the world has been forced to give remote work and Zoom-only conferences a test-drive, demand for commercial real estate and hotels specializing in business functions is unlikely to return to its pre-crisis level. And such permanent changes in demand mean that millions of sidelined workers will not regain their old jobs. Rather, new jobs will need to be created following the reallocation of capital across firms and sectors. That is an inherently gradual process. And in the interim, the resilience of elevated unemployment will dampen consumer spending, further delaying full recovery.

Of course, Congress’s fiscal response has not actually been perfect. Although the CARES Act’s unemployment-insurance provisions have been a laudable success — allowing poverty in the U.S. to fall even as joblessness hit Great Depression levels — its aid to small businesses was inadequate and poorly structured, while its failure to cover state and municipal budget shortfalls is fueling massive cuts in public spending and employment. Meanwhile, absent another relief package, enhanced unemployment benefits and a moratorium on evictions for Americans in publicly subsidized housing will expire by August, triggering a spike in poverty and homelessness.

But the biggest flaw in the V-shaped forecast was that it relied on a set of improbably rosy assumptions about the pandemic itself. Put simply, you can’t have a V-shaped recovery if your nation’s chart of new coronavirus cases looks like a bunch of Ws.

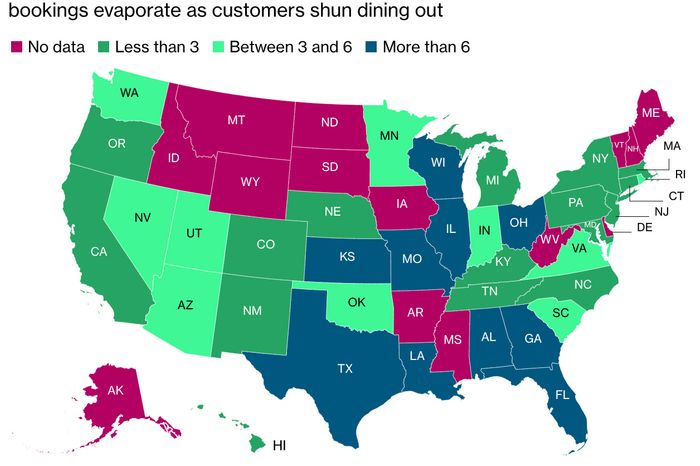

Earlier this month, data confirming the CARES Act’s efficacy in keeping households afloat, combined with encouraging economic numbers from freshly reopened states, lent the bullish outlook a patina of plausibility. But now, in Texas, Florida, and Arizona, hasty reopenings have spurred resurgent outbreaks — which have effectively re-shuttered much of the economy. As a Bloomberg analysis of restaurant-reservation data from OpenTable shows, demand for dining out has fallen back into decline through much of the South and Midwest.

Baby boomers supply roughly one-third of all consumer spending in the United States. Regardless of whether public officials order a second shutdown, if coronavirus is spreading exponentially through major population centers, older Americans are going to shop less, and low-margin businesses dependent on sales volume will fail. This was already ostensibly happening last month: Although the May jobs report showed (surprisingly) robust payroll growth, those gains came overwhelmingly from the reversal of temporary layoffs, as reopened businesses recalled furloughed workers. By contrast, the number of workers permanently fired in May was actually 295,000 higher than it had been in April. If COVID-19’s resurgence leaves reopened businesses with fewer customers than they anticipated, many workers who regained their jobs last month are likely to pass through a revolving door back onto the labor market’s sidelines — which are already quite crowded.

Another 1.48 million Americans filed for initial unemployment benefits last week. This figure represents a modest decline from the previous week, but it is also significantly higher than economists had anticipated. The fact that the economy is still shedding jobs at such an extraordinary clip — months into the crisis, with most state economies at least partially reopened — is indicative of long-term structural damage to the economy. Earlier this month, analysts warned that a second-wave of layoffs was poised to wipe out millions of white-collar managerial jobs in hard-hit sectors like leisure, retail, and hospitality (and that projection was compiled at a time when America’s public-health outlook appeared less ominous than it does today). On Thursday, Macy’s announced that it will be shedding nearly 4,000 corporate jobs.

On Wednesday, the number of new confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the U.S. hit an all-time high. Twenty-four hours later, Texas governor Greg Abbott announced an official “pause” to his state’s reopening. America’s economic and epidemiological outlook isn’t uniformly bleak. If Congress covers state and municipal budget shortfalls, and extends enhanced unemployment benefits — while Republican leaders encourage public compliance with mask-wearing and social distancing protocols — we’ll have a good chance of averting a depression.

By contrast, if the GOP keeps pretending that the only things ailing America’s private sector are overly generous welfare benefits and negligent business owners’ exposure to liability lawsuits, then our economy is going to get sicker.