The COVID recession has permanently eliminated 4 million jobs. Last month, the rate of employment gains slowed markedly, as fiscally embattled state governments laid off workers in droves. One in three U.S. families with children do not have enough to eat. Tens of millions of Americans are at risk of losing their homes. More than 97,000 small businesses shuttered for good.

The coronavirus did not do this.

Or at least not all of it. Even if we (absurdly) stipulate that the U.S. government couldn’t have handled the pandemic any better than it has, it could still be mitigating the economic toll better than it is. We know this because, earlier this year, it did: Thanks to the CARES Act’s relief checks and enhanced unemployment-insurance benefits, the U.S. enjoyed record-high personal-income growth at the height of its COVID outbreak. The aid was so effective, fewer Americans were living in poverty in June 2020 (amid a historic economic crisis) than in 2019 (at a time of historically low unemployment). And the benefits of helping the working class trickled up: As U.S. households spent their relief checks, retail sales rebounded, and the stock market soared. Meanwhile, the supposed pitfalls of multitrillion-dollar stimulus spending never materialized. America’s borrowing costs and inflation rate remain exceptionally low. According to the Federal Reserve — not an institution renowned for its socialism — more stimulus is desperately needed.

But congressional Republicans allowed the CARES Act’s relief provisions to phase out anyway. The recent slowdown in job growth is a direct consequence of this decision. And now the party is signaling that it’s no longer interested in replacing those relief provisions with scaled-down versions of the same.

“Nancy Pelosi is asking for $2.4 Trillion Dollars to bailout poorly run, high crime, Democrat States, money that is in no way related to COVID-19,” Donald Trump tweeted Tuesday afternoon. “We made a very generous offer of $1.6 Trillion Dollars and, as usual, she is not negotiating in good faith. I am rejecting their request, and looking to the future of our Country. I have instructed my representatives to stop negotiating until after the election when, immediately after I win, we will pass a major Stimulus Bill that focuses on hardworking Americans and Small Business.”

Mitch McConnell probably did not want the president to claim sole responsibility for the breakdown of stimulus talks. But according to the Washington Post, the Senate majority leader did advise Trump that “Pelosi was stringing him along and no deal she cut with Mnuchin would command broad GOP support to pass in the Senate.”

Which looks bizarre, on first glance. McConnell’s majority is living on a knife’s edge: In recent days, FiveThirtyEight declared Democrats the two-to-one favorites to control the Senate next year. The GOP still has a solid shot of retaining the chamber, but doing so will require most of its embattled incumbents (in South Carolina, North Carolina, Maine, Iowa, Colorado, and Arizona) to keep their seats. And many of those incumbents were eager to vote for a stimulus package that could shore up their bipartisan bona fides. McConnell may not value his constituents’ well-being or the health of our democracy. But he does seem to value his own power. So with his president and his majority on life support, why would he walk away from a chance to get $1,200 checks mailed to most Americans by Election Day?

After all, it’s not as if Pelosi is asking his caucus to vote for abortion vouchers funded by a wealth tax. As Trump’s tweet indicates, the key sticking point in negotiations is over fiscal aid to states and cities. But, contra the president, this is not a policy that only “Democrat States” have an interest in. Plenty of deep-red states are in dire fiscal shape due to a simultaneous pandemic-induced increase in health-care outlays and reduction in tax revenues. For this reason, back in May, Republican senators from Louisiana and Mississippi introduced a stand-alone bill that would deliver $500 billion “in emergency funding to every state, county, and community in the country.” The U.S. Chamber of Commerce endorsed that plan.

And yet Senate Republicans now consider aid to states so outrageous they’re willing to let the economy crumble one month before Election Day just to avoid dispensing such relief.

The most plausible explanation for this state of affairs is this: Most Senate Republicans face no great risk of losing their seats to a Democrat this year or any other. For them, the main threat to their power is a primary challenge. And right now, conservative media has turned opposition to fiscal aid into a cause célèbre, casting support for “blue-state bailouts” as treasonous. Thus, to pass a Pelosi-friendly stimulus deal out of the Senate, McConnell would have to bring a bill to the floor that a majority of his caucus would vote against. This would imperil his leadership. And so he is not going to do it.

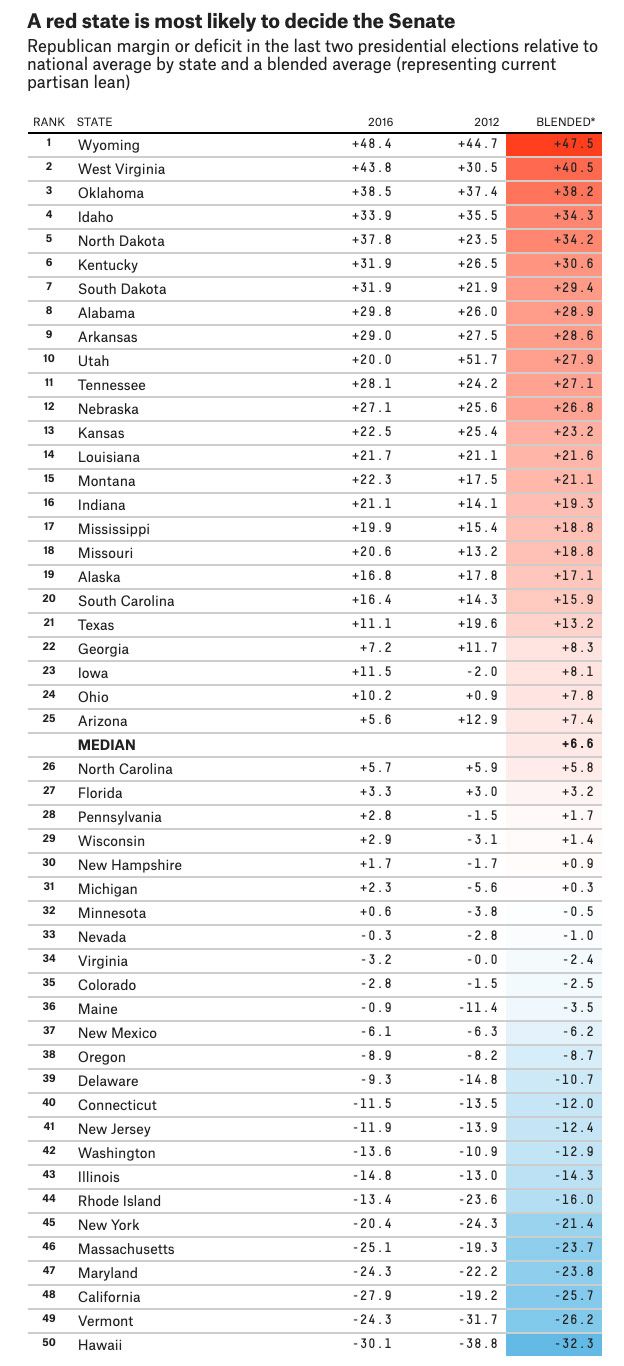

Assuming this is the case, it’s important to recognize the structural roots of the Senate GOP’s dysfunction. The reason so many GOP incumbents are more worried about primary challenges than Democratic opponents — and why McConnell is willing to prioritize their purity over aiding his most vulnerable members — is straightforward: The median U.S. state is 6.6 percentage points more Republican than America as a whole.

Thanks to urban-rural polarization — and our Republic’s abundance of scarcely populated rural states — Republicans have a massive built-in advantage in the Senate. This doesn’t just mean that many GOP incumbents hail from places where Democrats are few and far between. It also means that it is very hard for Republicans to ever be more than one solid midterm away from controlling the upper chamber.

And that’s key to McConnell’s calculus. Even without passing a stimulus, he still has a decent shot at a 51-vote majority. The races in North Carolina, Maine, and Iowa are all close. And the Democratic candidate in the Tarheel State is mired in an adultery scandal. What’s more, even if McConnell loses his majority, Democrats’ odds of holding more than 52 seats next January are quite low. Assuming a Biden victory, the GOP would have an excellent chance of winning back Senate control in 2022, as the opposition party almost always enjoys a major turnout advantage in midterm elections. By walking away from the stimulus, McConnell is prioritizing conservative ideology over personal power. But the political cost of doing this is relatively low.

By contrast, in a world where each party’s share of Senate seats roughly correlated with its share of the popular vote in the past three federal elections, McConnell’s prioritization would be untenable. As Ron Brownstein notes, “while the GOP has controlled the Senate for about 22 of the past 40 years, Republican senators have represented a majority of the nation’s population for only a single session over that period: from 1997 to 1998.” If McConnell’s grip on power were contingent on his party’s ability to retain the approval of a majority of voters, the political cost of letting the economy crumble before Election Day — to appease conservative media and big-dollar donors — would be prohibitively expensive. In such a system, the worst-case scenario facing McConnell would not be a 47-seat minority but rather a decimated caucus and multiple cycles in the wilderness. (And then, of course, if such a system had always been in place, the Senate GOP as currently constituted would not exist.)

This all spotlights a point that is often elided in the debate over the Senate’s structural biases. The problem with a congressional chamber heavily biased in the GOP’s favor is not merely that it disenfranchises America’s Democratic plurality. The problem is also that the Senate’s bias deforms the GOP by enabling it to ignore public opinion — and utterly betray the material interests of its own voters — without ever putting itself out of contention for federal power.

In a two-party system, voters who identify strongly with conservative positions on cultural issues have only one partisan option. Combine this fact with the heavy overrepresentation of such voters, and you end up with a Senate GOP that can sabotage the economy a month before Election Day and still retain a shot at retaining power. That is a problem for the Democratic Party. But it’s also a problem for the American polity — one that will cost many Americans their businesses, jobs, homes, and lives in the weeks to come.