Joe Biden won the 2020 election by appealing to voters who do not trust his party to govern.

Okay, that is a reductive and somewhat premature bit of punditry. The left-leaning voters and activists who mobilized to elect Biden were at least as important to his victory as moderate ticket-splitters were. But as the Democratic nominee’s popular-vote margin swells — while his party’s losses down-ballot multiply — it looks increasingly certain that Americans who favored Biden over Trump, but a GOP Congress over a Democratic one, make up a small but significant portion of the president-elect’s coalition.

Exactly how large this contingent is — and why it chose to split its tickets — remains unclear. But one thing we know is that Joe Biden did not campaign against the Republican Party as an institution. Rather, to help Trump-averse moderates reconcile their sympathy for Republicans with voting for a Democratic nominee, Biden emphasized his opponent’s personal unfitness for office while advertising the mutual admiration between himself and the John Kasichs of this world. This was a reasonable gambit that may well have won Biden a significant number of votes. But to the extent that it was possible for Biden to sell the electorate on the idea of unified Democratic government, advertising his own gifts for reaching across the aisle — while distancing himself from many of his own party’s most prominent policy ideas — was surely not the way to do it.

The question of how the Democratic Party can persuade voters to support it up and down the ballot is one the party will need to answer right quick. Despite the disappointments of November 3, Democrats still have an outside shot at securing full control of the federal government. In Georgia, winning a Senate election requires a candidate to win more than 50 percent of the vote; if no candidate clears that threshold, a runoff election is held between the top two finishers. This year, both of the state’s Senate races went to runoffs, with Republican Kelly Loeffler facing off against Democratic pastor Raphael Warnock, and Republican David Perdue taking on former Barack Obama impersonator Jon Ossoff. If Democrats sweep these races, they will have 50 Senate votes (which, with Kamala Harris’s tiebreaking vote as vice-president, qualifies as a bare majority).

Winning both of these races is a tall order for a lot of reasons. For one thing, in the first round of both contests, GOP candidates won a plurality of the vote. For another, parties that have just lost the presidency tend to overperform in any ensuing special elections, as their voters thirst for vengeance while the other side’s supporters get complacent. But given Biden’s apparent reliance on the support of ticket-splitters — both nationally and in Georgia — the biggest challenge Democrats face may be this: The party will need swing voters to support not one but two of its down-ballot candidates during the same trip to the ballot box.

The Biden-Trump race may have increased the prevalence of voters backing Democrats on the presidential level and Republicans below it. But the tendency for weak partisans (or nonpartisans) to favor divided government is deeply rooted in American politics and quite common in other democracies. Voters without strong or coherent ideological commitments seem to have a strong predisposition for hedging their bets. And Democrats will need to obliterate that tendency if they are to capture both remaining seats. After all, the party will need such voters to forgo the option of balancing their own ballots by picking one Democratic Senate candidate and one Republican one.

Thus, the party has no choice but to tackle the problem head-on by making a strong, affirmative case for unified Democratic government. To my mind, the best way to do this is to make voters understand what is actually at stake in whether Mitch McConnell or Chuck Schumer is majority leader: Namely, whether the next round of COVID stimulus legislation will be large or small.

McConnell has made it clear that his caucus will only support a modest and “targeted” COVID relief package. Senate Republicans have rallied behind a $500 billion package that includes forgivable loans to small businesses and a $300 weekly federal unemployment benefit but no aid to states and cities and no more $1,200 relief checks. Democrats, by contrast, back a $2.2 trillion stimulus that includes a $600 a week federal unemployment benefit, another round of relief checks, funding for states and cities, housing assistance, small business aid, and a variety of other social support. Critically, stimulus is one thing that Democrats can do without abolishing the filibuster, and which even the party’s most conservative senators are unlikely to block.

All available polling indicates that the voting public favors the Democratic position. In a New York Times–Siena College survey from late last month, 72 percent of voters, including 56 percent of Republicans, backed a $2 trillion stimulus modeled after the House Democrats’ proposal. Of course, the 2020 election taught us that polls are likely undersampling Trump supporters. But national polls look like they will be off by only three or four points. Double that error — stipulate, baselessly, that all of the undersampled Trump voters out there also oppose large-scale stimulus — and you still end up with 64 percent of the public favoring the Democratic approach.

And the party may be able to compound that advantage by spotlighting the concrete consequences of taking a more austere approach to relief. Faced with COVID-induced revenue shortfalls — and little fiscal support from Congress — Georgia cut its 2021 budget by 10 percent, slashing nearly $1 billion from K–12 education. A Democratic Congress would deliver a level of fiscal support to states that would make it possible for Georgia to avoid defunding its public schools. A Republican Congress wouldn’t. Ossoff, Warnock, and their party should make sure Georgia voters understand that. (Ironically, the GOP is also doing more to “defund the police” than the Democrats are, as Republican opposition to fiscal aid to cities has led many jurisdictions to reluctantly lay off cops.)

Perdue and Loeffler may try to co-opt a pro-stimulus message, just as other Republicans have done on the issue of health-insurance subsidies for people with preexisting conditions. But if so, that would be a minor victory in itself. Unlike that health-care issue, which will only become salient in the unlikely event that the Supreme Court strikes down the ACA, COVID stimulus will be the No. 1 legislative fight of the coming weeks and/or months. If Perdue and Loeffler embrace generous fiscal aid to states and more relief checks on the stump, they will need to then support it in Congress, or else violate a campaign promise on a high-profile issue immediately after winning election (something politicians are typically reluctant to do, even in our grossly undemocratic age). Thus, making the Georgia runoff into a referendum on stimulus is both a sound strategy for winning a Democratic Senate and also, potentially, a means of tilting the center of political gravity on coronavirus relief to the left, even if Democrats lose.

To be sure, one flaw in this argument is that it makes sense to me — and, generally speaking, what makes sense to me and what makes sense to swing voters don’t overlap much. Given that Donald Trump just won millions of more votes in 2020 — after treating the country to four years of wanton corruption that culminated in his actively exacerbating a mass-death event — it might seem wise for progressive pundits to distrust their every intuition about how the marginal voter sees the world.

That said, from some angles, the relatively widespread support for Trump looks more rational than liberals may be inclined to recognize.

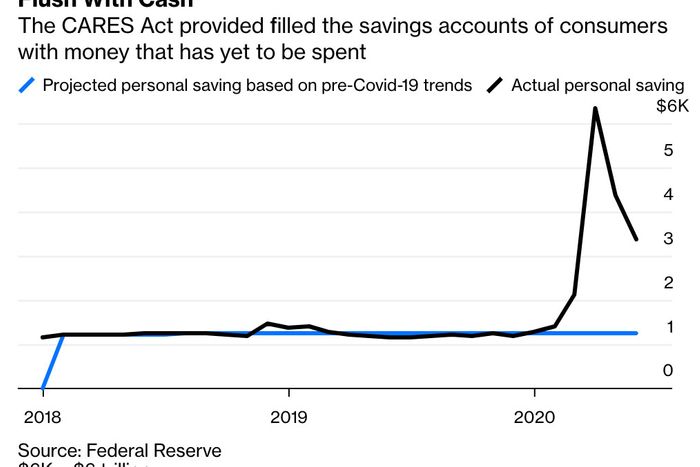

Trump inherited an economic expansion, which he then fortified by appointing a dovish Federal Reserve chair and signing off on giant fiscal stimulus in the form of tax cuts (primarily for the wealthy) and spending increases (primarily for the military). By the end of 2019, this had brought unemployment lower, and wages higher, than at any time in recent memory. COVID plunged the economy into recession, of course. But thanks to the CARES Act’s unprecedentedly robust fiscal support, the Federal Reserve’s interventions in credit markets, and the sudden contraction in consumption opportunities, average disposable income in the U.S. massively increased over the course of 2020: For middle-class Americans who did not lose their jobs or suffer a pay cut (a category that includes the vast majority of middle-class Americans), the COVID pandemic brought a $1,200 check from Uncle Sam and less temptation to spend that money on a vacation. As a result, a wide swath of the country is in better financial health than it has ever been in (even as a record number of Americans are suffering utter financial devastation).

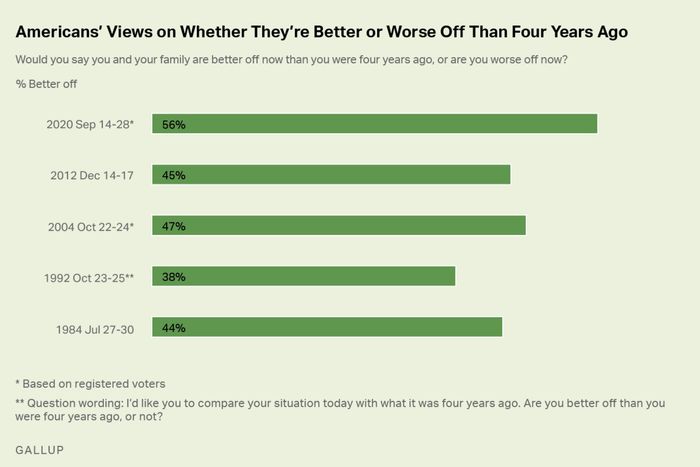

And voters’ self-evaluations of their economic well-being reflect this: In September, 55 percent of Americans told Gallup they were better off now than they were four years ago; in 2012 and 2004, years when the incumbent president won reelection, a majority of Americans did not say the same.

All of which is to say: It’s quite possible that a generous COVID stimulus package was what kept Trump competitive in 2020. If so, it stands to reason that the promise of another such package just might keep Democrats competitive in Georgia next January.