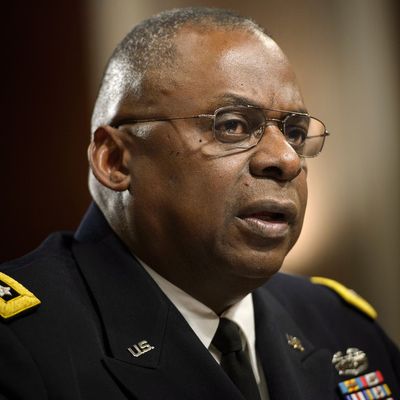

To date, President-elect Joe Biden’s cabinet picks have inspired predictable controversies. Will progressives object to this or that hire? Will the White House be as diverse as promised? Will the Biden administration simply become a jobs program for veterans of the Obama administration, or will he branch out? But Biden’s latest pick may face resistance for an entirely different reason. In nominating Lloyd Austin to be the secretary of Defense, Joe Biden repeats one of President Trump’s most dangerous assaults on democratic norms.

Austin, a retired Army general, would need a waiver from Congress to lead the Pentagon, and some Democrats are reluctant to grant it. Instead of the usual left-center split about Biden’s nominees, centrists and progressives alike have said they’re concerned by Austin’s nomination owing to a long-standing precedent with bipartisan support: The U.S. military is subject to civilian control. That firewall exists to protect the democratic process from military interference. The role of Defense secretary is thus designed by law for civilian occupancy. Austin would need a waiver because he separated from active-duty service less than seven years ago.

When Trump nominated James Mattis, a recently retired Marine general, to the same position in 2017, the president’s critics widely condemned the decision. At the time, some worried that Mattis’s need for a waiver might establish a worrying precedent, and now, three years later, Biden has proved them right.

So the usual factional lines are a little scrambled. Representative Elissa Slotkin of Michigan, a former CIA analyst who also served as acting assistant secretary of Defense, does not belong to her party’s left wing, but she has indicated that she might not vote for a waiver.

In comments to Politico, Democratic senator Richard Blumenthal also said he won’t approve a waiver for Austin. Senator Jack Reed was more equivocal, saying that while “the quality of the nominee” should be “the decisive factor,” he’d prefer “someone who’s not recently retired.” Senator Bernie Sanders, meanwhile, may be at odds with both of his colleagues: He told NBC News’s Katy Tur on Tuesday that he’s currently inclined to support the waiver.

Though Austin’s need for a waiver has proven to be the most controversial aspect of his nomination, other entries in his record may also give Democrats pause. He sits on the board of Raytheon, one of the nation’s preeminent corporate war profiteers. He should also face questions over his handling of our longest war. As the head of U.S. Central Command, Austin served as our top commander in Afghanistan while military officials lied repeatedly to the government and the public about our country’s chances of victory.

Given Austin’s baggage, it’s incredible that Biden chose to nominate him at all. But on Tuesday, the president-elect defended his choice in a lengthy editorial in The Atlantic. Citing Austin’s credentials and military experience, Biden urged Congress to approve a waiver for his nominee. “I respect and believe in the importance of civilian control of our military and in the importance of a strong civil-military working relationship at DoD — as does Austin,” wrote President-elect Biden. The Department of Defense “needs empowered civilians,” he added, before promising that Austin will “work tirelessly” to repair the civil-military dynamic that Trump placed under so much stress.

But CNN’s Jake Tapper has also reported that the president-elect may have gravitated toward Austin in part for personal reasons. The retired general was close to Biden’s late son, Beau.

Biden’s ability to empathize with families in grief probably helped win him the election. Next to Trump, he seemed relatable and compassionate. But sentiment isn’t a good reason to violate one of our most important democratic precedents. Biden’s stated justifications are equally unpersuasive. There’s more than civilian control of the military at stake. Military service should not be a qualification for high office of any kind, but post-9/11, both parties have increasingly exalted public servants who put military service on their résumés. There is little space left for critics of war and little opposition to a jingoism that principally serves the right wing. When it comes to war, there is hardly any difference between the two major parties at all. That has already been disastrous for our political culture, for generations of civilians and service-members alike, and for the rest of the world, which we frequently hold hostage to our whims. We can’t afford another four years of the same.