Less than two months after inciting an insurrection against the U.S. Congress, Donald Trump will reportedly declare himself the Republican Party’s “presumptive 2024 nominee” at this weekend’s Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC).

And he won’t be wrong.

Losing an election is typically enough to sour a party’s voters on its defeated standard-bearer. Fumbling a half-assed coup attempt is, in most countries, enough to get an ex-president imprisoned or even killed. But red America’s consummate “winner” has emerged from electoral and insurrectionary defeat with his grip on the GOP faithful intact. Last week, a Politico-Morning Consult poll found that 59 percent of Republican voters would like Trump to “play a major role” in their party going forward — up 18 points since January 7, the day after the Capitol Hill riot. The survey also found that a large plurality of GOP voters specifically want Trump to play the role of 2024 Republican nominee.

A Suffolk University/USA Today survey, meanwhile, finds that if the GOP’s 2020 coalition is forced to choose between Trumpism and Republicanism, the former will win in a landslide. By a margin of 46 to 27 percent, Trump 2020 voters said that if the former president ditched the GOP and started his own political party, they would follow their leader out of the Republican tent. Myriad other surveys have documented the same political reality. Donald Trump is deeply unpopular with the general public, and disliked by a minority of Republican voters. But no one in red America commands more legions of ultraloyal stalwarts, and for this reason, few if any Republicans are better positioned to unite their coalition — a point that Trump’s team will surely emphasize when they mingle with GOP megadonors at their forthcoming retreat.

The GOP isn’t just renewing its vows to Trump himself, but also to the unabashedly antidemocratic politics he represents. In Republican-controlled statehouses across the U.S., GOP lawmakers are introducing a cornucopia of voter-suppression measures. In Arizona, Republicans are trying to deter voter-registration drives and restrict access to mail-in voting. In Pennsylvania, the GOP has introduced four separate bills abolishing no-excuse absentee voting. In Georgia — ground zero for Trump’s “stop the steal” campaign — Republicans have taken direct aim at the Black electorate by proposing a law against early voting on Sundays, when African-American churches have historically led their congregations to the ballot box, in a tradition known as “souls to the polls.”

Joe Biden famously predicted that Trump’s defeat would spark an “epiphany” among Republican officialdom, compelling the party to forswear illiberal demagogy and embrace the compassionate conservatism of yesteryear. Instead, seeing their champion felled has only redoubled conservatives’ appetite for authoritarianism. This is an ominous development for the American experiment. But for those of us who wish to fend off right-wing minority rule, the conservative movement’s decision to keep its mask off has some upside — because the only thing more dangerous than an overtly antidemocratic GOP may be a covertly antidemocratic one.

Republican voter-suppression efforts are vast in number, but limited in efficacy.

The GOP’s attempts to restrict ballot access are shameful. But they are also unnecessary for subjugating America’s Democratic majority to perennial Republican rule — and may even be counterproductive to that project. In truth, the threat to popular self-government in the U.S. derives less from the GOP’s suppression of Democratic turnout than our constitutional order’s systematic underrepresentation of Democratic voters.

America’s voting-age population is bluer than its electorate. But this is less true today than at any time in modern history. As college-educated voters have shifted left, while non-college-educated voters have shifted right, the GOP’s objective interest in making voting more difficult has lessened. Put simply, affluent suburban professionals are much harder to disenfranchise than the rural poor, and there are very few voting restrictions that burden low-income Democratic voters without also burdening low-income Republican ones. If Georgia Republicans pass a newly introduced bill requiring voters to submit a photocopy of their ID with their mail-in ballots, they may learn this the hard way. As Kathleen Unger, president of the voter ID assistance group VoteRiders, noted in an interview with Bloomberg that that requirement will be “particularly onerous for people who don’t have a valid photo ID or easy access to a copy machine or a printer,” a population that skews old, non-college-educated, and rural-dwelling; in other words, it is a voting restriction that might very well suppress GOP turnout.

The GOP can try to target their suppression efforts narrowly at minority groups, as the ban on Sunday early voting in Georgia seeks to do. But such blatant racial discrimination can abet Democratic mobilization drives (few sentiments motivate turnout better than “they don’t want you to vote”) and alienate racially enlightened moderate voters. As Bloomberg’s Ryan Teague Beckwith writes:

A 2016 study published in Political Psychology found evidence that the debate over voter ID laws angers Democrats, making them more likely to vote, while a 2019 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that in states with strict voter ID laws, non-White voters were 5.4 percentage points more likely to be contacted by a campaign than in other states.

The recent Senate runoff elections in Georgia seem to bear that out. In a state long known for restrictive voting laws, Abrams and other activists led a decade-long effort to reach out to disengaged young and Black voters, helping them register and vote.

For these reasons, many Republican strategists oppose the voter-suppression efforts on strictly amoral grounds. As one told the Washington Post last week, “There’s still an appetite from a lot of Republicans to do stuff like this, but it’s not bright. It just gives Democrats a baseball bat with which to beat us.”

This isn’t to say that Republican voter-suppression efforts aren’t a problem. On net, they likely reduce Democratic vote share, especially when one considers disparities in funding for electoral infrastructure between urban and rural areas. And voting restrictions that formally bar left-leaning constituencies from casting ballots — such as felon disenfranchisement laws — are doubtlessly effective at their nefarious aim.

Nevertheless, restrictive voting laws take a far smaller toll on popular sovereignty in the U.S. than the biases of our constitutional framework do.

Republicans don’t need to disenfranchise America’s Democratic majority, because our constitutional order will do that for them.

Thanks to a combination of 19th-century efforts to gerrymander the Senate and the intensification of urban-rural polarization over the past decade, the median U.S. state is far more white, rural, and Republican than the nation as a whole. According to FiveThirtyEight’s calculations, the “tipping point” state for control of the U.S. Senate is roughly 6.6 percent more Republican than the national electorate. This not only gives the GOP a massive advantage in the race for Senate control, but also in the battle to dominate state governments. In fact, America’s state legislatures are so biased in the GOP’s favor, Republicans emerged from the 2018 and 2020 election cycles, in which their party lost the national vote by large margins, boasting full control of 23 state governments, which is eight more than Democrats command. This state-level dominance will enable Republicans to exert more influence over congressional redistricting than their rivals, thereby gerrymandering the House of Representatives in conservatives’ favor for a decade to come.

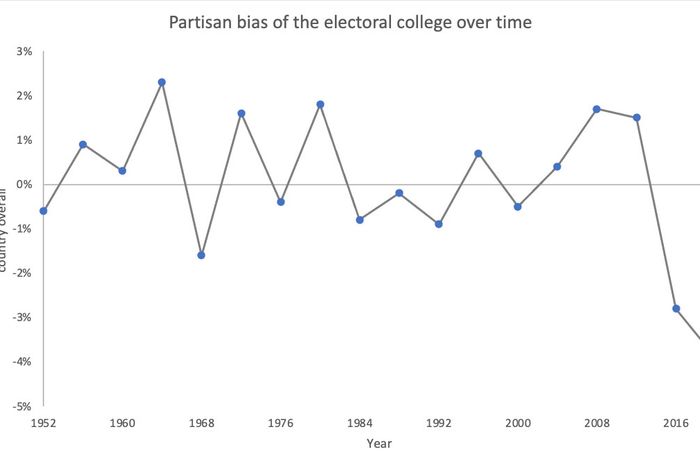

The Electoral College does not systematically underweight urban voters, so much as it gives outsize influence to whichever populous states happen to be evenly divided at a given time. Unfortunately, in the present context, this also benefits Republicans, as the Rust Belt’s rightward drift has left the Electoral College biased four points in the GOP’s favor.

The collective impact of these structural advantages dwarfs the marginal gains that Republicans can engineer through vote-ID laws. More than that, they render such penny-ante authoritarianism unnecessary. The conservative movement fears multiracial democracy, but that fear is irrational, as long as it stipulates that America’s existing constitutional order qualifies as “democratic.” Republicans have an excellent shot of retaking the House in 2022 on the strength of redistricting alone. They are overwhelmingly likely to win back the Senate in 2024, when Democratic incumbents who eked out reelection in the 2018 wave will face voters again in a less favorable environment. And given the Electoral College’s slant, if the GOP nominee loses the popular vote by 3 percent or less in 2024, he or she will have an excellent shot at winning the presidency.

All the GOP needs to do to win back full federal control by 2024 is (1) avoid the kind of landslide defeats that Trumpism brought them in 2018 and 2020, and (2) make sure Democrats don’t use their tenuous grip on power to make America’s representative bodies less hostile to blue America.

Reaffirming the Republican Party’s commitment to voter suppression — and a heinously unpopular insurrectionist — seems counterproductive on both these fronts.

Trumpism may have helped accelerate the drift of non-college-educated, rural voters into red America. But now that the Trumpen proletariat is in the GOP’s corner, demagogic denunciations of Joe Biden’s fictional support for police abolition and open borders should be sufficient to keep them there (or rather, such demagogy would be sufficient, if Donald Trump weren’t dead set on retaining his personality cult). On the other hand, if the GOP would simply dog-whistle its appeals to white racial animus, instead of blasting them through Trump’s foghorn, it would likely make greater inroads among nonwhite, working-class voters, while winning back a chunk of affluent suburbia’s “woke” opponents of progressive taxation and inclusionary zoning.

Further, by abandoning Trump’s rhetorical extremism, and his open contempt for the rule of law, the conservative movement could regain much of the legitimacy that it once enjoyed among America’s media and political elite. Trump’s refusal to safeguard his party’s plausible deniability on matters of race and democracy won him far more adversarial coverage from the mainstream media than any of his Republican predecessors. Making largely superficial concessions to elite sensibilities (e.g., pursuing minority rule through gerrymandering instead of voter suppression) wouldn’t just aid Republicans electorally by securing them more favorable press; doing so would also fortify moderate Democratic opposition to structural political reforms.

The conservative movement has nothing to fear but Joe Manchin’s fear of the conservative movement itself.

It is possible that Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema’s commitment to sacrificing American democracy on the altar of the filibuster needs no reinforcement. But had the GOP abandoned Trump post-2020, and forswore voter suppression, it would be even harder to imagine moderate Democrats agreeing to exempt democracy reforms from the legislative filibuster than it is today. By rallying behind a twice-impeached demagogue who sicced a mob on Senate Democrats, while pushing for voter-suppression laws in the states, Republicans are making a stronger case against respect for bipartisan norms than progressives ever could.

Since the threat of right-wing minority rule derives primarily from structural biases that can only be redressed at the federal level, the critical obstacle to safeguarding the republic against that threat is, ultimately, moderate Democrats in the Senate, not radical Republicans in statehouses. Chuck Schumer’s caucus will either unite behind banning partisan redistricting, awarding statehood to D.C., Puerto Rico, and any other U.S. territory that wants it, and expanding the electorate through reforms that make voting easier — or it will clear the way for the radical right to reclaim power in defiance of the popular will, even if Republican governors veto every voter-suppression measure that comes to their desks between now and 2024.

In a better world, on the morning after Trump’s defeat, all Republican officials would have woken to find themselves transformed into Nelson Rockfeller. The RNC would have released a statement disavowing their party’s half-century of reactionary extremism and vowing to bring its agenda into congruence with those of center-right parties in the rest of the developed world. Mitch McConnell would have tearfully apologized for abetting the entrenchment of plutocracy. Tom Cotton would have resigned from the Senate to signal his contrition for fooling American workers into believing immigrants posed a greater threat to their economic security than union-busters do. Louie Gohmert — eyes wet, lips trembling, chin flecked with snot and spittle — would have stammered that white, conservative Christians have no greater claim to this land than other Americans do, before joining his fellow Republicans in giving Joe Biden a great big group hug.

But in the world we actually live in, there was no serious prospect of the GOP reforming itself in the wake of Trump’s defeat — not least, because its structural advantages largely shielded down ballot Republicans from the electorate’s rebuke. Any break with Trumpism was going to be marginal, if not outright cosmetic. The GOP will only moderate if Democrats enact reforms that force it to do so. If the conservative movement’s refusal to camouflage its contempt for democracy makes Senate Democrats less complacent about minority rule, an openly authoritarian GOP may be preferable to the alternative.