Barring a medical emergency or sudden outbreak of austerity fever, Joe Biden’s nearly $2 trillion COVID relief bill will be law by mid-March. After that, congressional Democrats plan to turn their attention to a climate-friendly infrastructure package. Like the president’s “relief” bill, this “recovery” program will consist primarily of spending measures, and almost certainly be passed via a budget-reconciliation bill — a special category of legislation that can pass the Senate on a party-line vote, so long as all its provisions primarily impact the federal budget.

But once reconciliation is done, acrimony may follow.

Through the opening weeks of the Biden presidency, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema have held the line against altering the legislative filibuster. To progressives’ dismay, these Democratic senators have forced their party to advance relief through a byzantine process that has delayed the bill’s passage and narrowed its scope. Nevertheless, since the bulk of Biden’s first big bill was reconciliation eligible, the moderates’ fetishization of the filibuster has condemned their party to headaches — but not yet to paralysis. Soon, that will change.

On Wednesday, House Democrats passed the “For the People Act,” the package of anti-corruption and voting-rights reforms that Nancy Pelosi’s caucus has treated as its top priority since taking control of the House in 2019. Among the 800-page bill’s myriad provisions are a national system for automatic voter registration, a ban on partisan redistricting, and the establishment of public financing for federal campaigns. Congressional Democrats are nearly unanimous in their support for the legislation, and a supermajority of the U.S. public has endorsed its core provisions in opinion polls. More critically, since the House map already has a roughly three-point bias toward Republicans — and since the GOP controls 30 state legislatures to the Democrats 18, and will therefore dominate the redistricting process after the 2020 census — if Democrats don’t ban partisan redistricting in the next few months, their odds of retaining the House in 2020 will fall swiftly toward zero.

Meanwhile, in states across the country, Republicans are doing their darndest to lend further urgency to the cause of federal voting reform. At least 33 states have introduced, prefiled, or extended bills to make voting harder since the start of this year. In Georgia — ground zero for Donald Trump’s “stop the steal” campaign — Republicans have taken direct aim at the Black electorate by proposing a law against early voting on Sundays, when African-American churches have historically led their congregations to the ballot box, in a tradition known as “souls to the polls.”

None of this is lost on the Democratic leadership. Last year, in his eulogy for John Lewis, Barack Obama argued that honoring the civil-rights hero’s legacy required his party to pass sweeping voting-rights reforms — and stipulated that if it takes “eliminating the filibuster, another Jim Crow relic, in order to secure the God-given rights of every American, then that’s what we should do.”

In recent days, House Democrat John Sarbanes echoed Obama’s argument, telling Vox, “If Mitch McConnell is not willing to provide 10 Republicans to support [the For the People Act], I think Democrats are going to step back and reevaluate the situation. There’s all manner of ways you could redesign the filibuster so [the bill] would have a path forward.”

In the Senate, Minnesota’s Amy Klobuchar — no one’s idea of a progressive firebrand — vowed to send the bill to the Senate floor. If Republican support is founding wanting, Klobuchar said that her committee will ask itself, “Is there [a] filibuster reform that could be done generally or specifically?”

To some ears, Joe Manchin appeared to answer this question in the negative on Monday. Asked by the Hill’s Jordain Carney whether there is any scenario in which he might “change his mind” about the filibuster, Manchin replied, “Never! Jesus Christ! What don’t you understand about never?”

But Manchin also recognizes the necessity of voting-rights reform; or at least, he recognized it as of last August.

And there is some ambiguity in what Manchin meant when he said he’ll never change his mind “on the filibuster.” Perhaps the West Virginian will never condone killing the rule outright, but would consider reforming it, given the right circumstances.

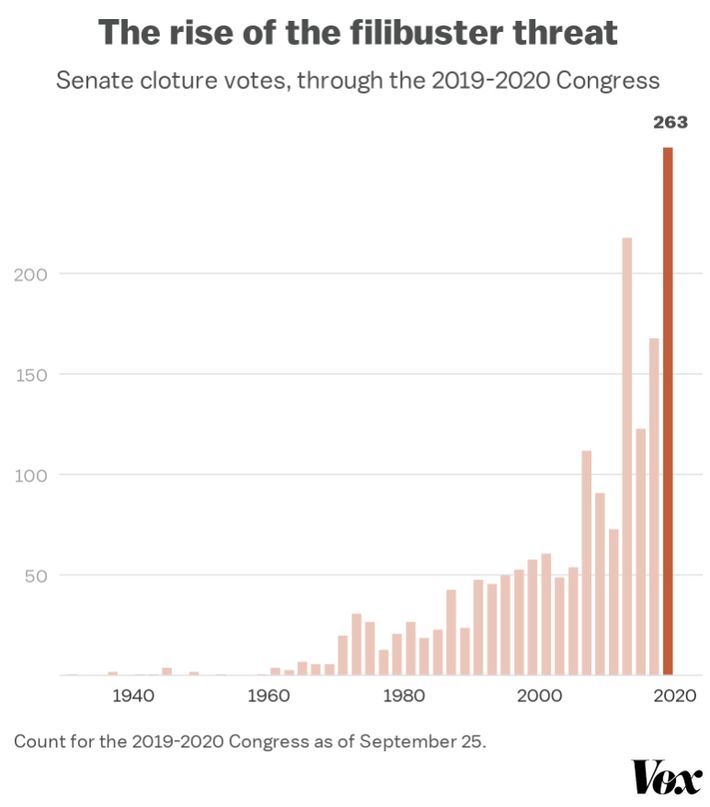

In truth, the filibuster is not actually a malign tradition that subverts the Constitution, erodes democratic accountability, and forces the global hegemon to pass all its major laws through a process more riddled with insane and arbitrary rules than a game of King’s Cup played by teens tripping on psilocybin — because it isn’t actually a tradition. The filibuster has existed in its contemporary form — as a default 60-vote requirement for all major legislation — for less than two decades. The period of the automatic 60-vote threshold has not been characterized by bipartisan comity (as the filibuster’s defenders routinely imply), but by its very opposite.

Therefore, if Manchin is earnestly concerned with defending long-standing Senate traditions and promoting bipartisan debate, then Democrats could simply restore the more rigorous requirements for sustaining a filibuster that prevailed through most of the 20th century. As Norm Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute writes:

Currently, it takes 60 senators to reach cloture — to end debate and move to a vote on final passage of a bill. The burden is on the majority, a consequence of filibuster reform in 1975, which moved the standard from two-thirds of senators present and voting to three-fifths of the entire Senate. Before that change, if the Senate went around-the-clock, filibustering senators would have to be present in force. If, for example, only 75 senators showed up for a cloture vote, 50 of them could invoke cloture and move to a final vote. After the reform, only a few senators in the minority needed to be present to a request for unanimous consent and to keep the majority from closing debate by forcing a quorum call. The around-the-clock approach riveted the public, putting a genuine spotlight on the issues. Without it, the minority’s delaying tactics go largely unnoticed, with little or no penalty for obstruction, and no requirement actually to debate the issue.

One way to restore the filibuster’s original intent would be requiring at least two-fifths of the full Senate, or 40 senators, to keep debating instead requiring 60 to end debate. The burden would fall to the minority, who’d have to be prepared for several votes, potentially over several days and nights, including weekends and all-night sessions, and if only once they couldn’t muster 40 — the equivalent of cloture — debate would end, making way for a vote on final passage of the bill in question.

Alternatively, Democrats could bring back the “present and voting” standard, which would similarly require the minority party to maintain constant vigilance in order to obstruct pending legislation. Under such a standard, three-fifths of the senators present in the chamber at any given time can vote to end debate and proceed to a vote on a given bill (once debate is ended, only a majority is required to pass a bill). In concrete terms, this means that if Democrats keep their caucus united and in the building, if Republicans ever let 17 of their members go home at the same time, then Chuck Schumer’s caucus would suddenly comprise a three-fifths majority and be able to end debate.

Georgia senator Raphael Warnock has floated a less elaborate path forward: If the Senate has a special filibuster exemption for budgetary bills, why shouldn’t it also have one for democracy reforms? Protecting the rights of the Senate minority might be a worthy aim, but surely, protecting the voting rights of America’s racial minorities is even worthier. Could Joe Manchin really deny that allowing a group of lawmakers who represent a small (overwhelmingly white) minority of U.S. voters to fortify their own party’s overrepresentation, by safeguarding its power to gerrymander the House and suppress the vote, is a greater affront to our republic’s highest ideals than ending a tradition that was born this century?

Maybe. Joe Manchin believes some pretty dumb stuff.

But even if so, a basic fact remains: Within the next few months, prioritizing the filibuster over the Democratic agenda is going to become a lot more uncomfortable for Manchin and Sinema than it is today. It is one thing to defend the filibuster when doing so makes your party’s current legislative priority more arduous to pass; it’s another when doing so makes that priority impossible to advance. Notably, voting-rights and democracy-reform bills aren’t the only forthcoming legislative fights that could test the moderates’ resolve.

The pending $1.9 trillion COVID relief bill would establish a nearly universal child benefit that would provide U.S. families with $3,600 for each child under the age of 6, and $3,000 for those up to age 17. This benefit would be dispersed in “periodic” installments, such that households would begin to factor the payments into their routine budgeting.

But the benefit is only slated to last a single year: In order to keep the price tag of the relief package under $2 trillion, Democrats put an expiration date on the provision.

All this means that there is going to come a point in 2022 when Democrats will need to either extend the child benefit, or allow just about every middle-class family in the U.S. to see its disposable income shrink, shortly before a midterm election.

The party might be able to slip an extension into a reconciliation bill. And it’s conceivable that effectively repealing an existing social benefit would be so politically toxic, ten Republican senators will be willing to vote to make the measure permanent.

But if the GOP declines to play ball, and Democrats use up their reconciliation bills, then Manchin and Sinema could end up in a place where gutting the filibuster is the least controversial of their options. Partisan hardball may run counter to the senators’ personal brands. But better to be seen as a partisan than as a person who took food out of the mouths of children all across your state.

It’s entirely possible that Democratic leaders will spare Manchin and Sinema from having to choose between extending the child benefit and weakening the filibuster. And it’s equally plausible that the senators will feel comfortable letting the For the People Act die to keep their own “bipartisan” bona fides alive.

But progressives can find some hope in the possibility that moderates’ resistance to filibuster reform will weaken as the costs of protecting Mitch McConnell’s power rise.