Moderate Republicans are accusing Joe Biden of secretly plotting to enact the policies he campaigned on.

In interviews with Politico Wednesday, staffers for the “G-10” — a group of ten Senate Republicans with an ostensible appetite for compromise — claimed that the president’s avowed interest in bipartisanship is insincere. In their account, Biden’s negotiations with the G-10 over infrastructure are a mere formality; his true intention is to make Republicans an offer they can’t accept, then use their refusal as a pretense for passing his $2.25 trillion plan through budget reconciliation.

The staffers’ complaints are sufficiently colorful (and, if one leans left, schadenfreude-inspiring) to quote at length:

It starts with what they see as some hardwired media narratives they can’t shake: that Biden is a reasonable, deal-making moderate and that Republicans talk about compromise but really just want to obstruct. It’s a perception that has given the White House all the leverage.

“Biden is a horrible villain for us,” said the G-10 staffer, meaning not that he was an actual villain but that he was difficult to villainize. “There are deeply entrenched narratives that have some truth but are no longer totally true. Reporters believe them despite all evidence to the contrary.”

They see a White House “constantly rubbing dirt in the face of Republicans” over the party’s lack of interest in bipartisanship while “passing as many partisan bills as they possibly can through reconciliation before they lose the House in 2022.”

…“Everything they support is defined as either Covid relief or infrastructure, and everything they oppose is like … Jim Crow voter suppression and evil,” this G-10 aide said. “And you constantly just feel like you’re in this gaslighting chamber of insanity. But it’s working.”

This read of Biden’s intentions isn’t necessarily accurate. The president has publicly suggested that he’s willing to scale back his proposal’s spending and adjust its tax hikes in order to win Republican buy-in. And there’s reason to think that gesture is sincere — even if one assumes that Biden is unwaveringly committed to every provision in his plan. After all, the president’s “Build Back Better” agenda is already split into two separate proposals — the infrastructure one currently being debated and a forthcoming package of social-welfare programs and investments in education. The conceptual distinctions between these two bills is already fuzzy; the “infrastructure” portion includes $400 billion for at-home care for the elderly, while the social-welfare-centric bill features universal pre-K and free community college (an investment in “human infrastructure” if there ever was one). Thus, if Biden can win a “bipartisanship” merit badge by passing part of his infrastructure agenda with GOP support — and then toss whatever provisions Republicans reject into the second bill, which Democrats could proceed to pass through budget reconciliation — he’d probably be inclined to do so. The only downside to such a scheme is that it could dampen moderate Democrats’ appetite for round two. But the gambit could also have the opposite effect: Having established their capacity to make bipartisan deals on some issues, Joe Manchin and his ilk may feel more comfortable returning to partisan lawmaking.

Regardless, the Republicans’ frustrations aren’t baseless. Democrats’ supposed attempt to strike a bipartisan compromise on their $1.9 trillion COVID-relief bill really was a perfunctory gestures; within 24 hours of the White House’s meeting with the G-10 in February, Chuck Schumer initiated the reconciliation process. Further, Biden’s decision to prioritize full employment and aid to the needy over making Senate Republicans feel important was a genuine departure from precedent; under Barack Obama, Democrats were far more invested in winning the hearts and minds of Olympia Snowe & Co.

Biden may well end up cutting a deal with the GOP on infrastructure (it’s possible that Manchin will leave him no other choice). But the fear that Republican staffers tacitly expressed to Politico — that their party lacks the leverage it’s used to exercising over Democratic presidents — is well-founded. Biden has little incentive to curb his ambitions for bipartisanship’s sake. There are (at least) five reasons why this is the case:

1) Biden’s agenda is popular.

Many worthwhile policies are politically challenging. For example, any attempt to significantly reform the American health-care sector comes with a high risk of backlash. Deep-pocketed groups have an existential interest in perpetuating the system’s dysfunction, while a lot of middle-class Americans are complacent about their private coverage, distrustful of their government, and anxious about any change that could theoretically threaten their access to existing providers. Together, these two realities enable health-industry lobbies to depress support for reform through well-financed propaganda campaigns.

But infrastructure is a different story (even under Biden’s broad definition).

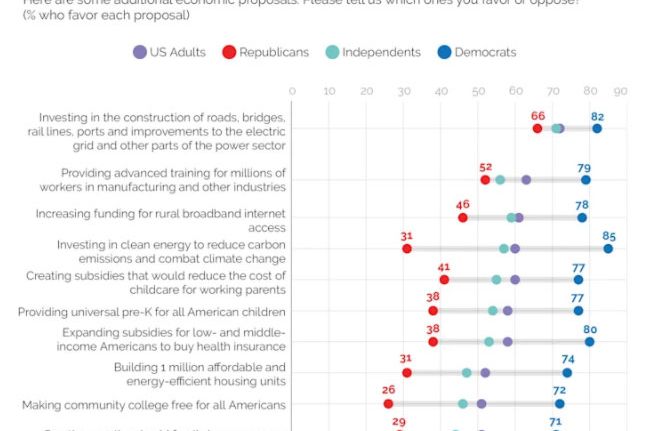

The president’s plan doesn’t leave powerful interests unscathed; it would raise the corporate tax rate from 21 to 28 percent. Just four years ago, however, the top corporate rate was 35 percent. A strong public-health-insurance option would threaten the long-term survival of major corporations; a statutory rate that is only seven points lower than it was in 2017 would not. Meanwhile, even if industry decided that defeating Biden’s tax hikes were a matter of life and death, their capacity to demagogue the issue would be limited. It’s hard to make voters afraid of better-paved highways, new manufacturing jobs, at-home care for the elderly, or any of the American Jobs Plan’s other components. Recent polls from Morning Consult and YouGov suggest that virtually every item in Biden’s proposal commands supermajority support, while 65 percent of voters endorse paying for the measures through a corporate tax hike.

All of which is to say: This is not the Affordable Care Act. Democrats are not proposing anything politically risky and thus have less need for “bipartisan cover” than they did during the battle over Obamacare 12 years ago.

2) Democrats just learned that they can pass a large, popular bill on a party-line vote without incurring a backlash.

Last month, Democrats passed a nearly $2 trillion law through budget reconciliation, while making only a few concessions to their own moderate members and none to Republicans.

And more than 70 percent of voters approved.

Ultimately, Biden’s decision to prioritize the pursuit of Republican validation did not cost him or his agenda public support; in fact, doing so did not even cost him Republican validation! Faced with the overwhelming popularity of the Democrats’ partisan relief bill, multiple GOP Congress members publicly claimed partial ownership of a law that they had voted against, effectively vouching for Biden’s bonafides as a bipartisan dealmaker in the process.

In light of this experience, Democrats have no real incentive to trade their base’s priorities for Lisa Murkowski’s stamp of approval.

3) Conservative media isn’t terribly interested in demagoguing Biden’s fiscal policies (and Republicans may not want it to be).

As the polling cited above would suggest, rank-and-file Republicans just aren’t that titillated by debates over highway funding. They’re here for the culture war not budgetary battles. When the Democratic President was an African American man with the middle name Hussein, the Fox News faithful could interpret any mundane policy fight as an assault on America’s national identity, social order, and cultural values. But with an affable old white man in the White House, their appetite for alienation can only be satisfied by coverage of cancel culture and immigration. As the Washington Post’s Philip Bump noted last month, while the debate over COVID relief was raging on Capitol Hill, FOX News gave the purported “cancellation” of Mr. Potato Head an order of magnitude more coverage than the $1.9 trillion bill winding its way through Congress.

At times, the conservative media’s mercenary incentives are at cross-purposes with the GOP’s political ones. But in this context, it’s probably in the Republican Party’s best interests for their propaganda arm to focus on defending racist Dr. Seuss cartoons and fomenting proto-fascist xenophobia. The GOP’s few, feeble attempts to demonize Biden’s fiscal policies have fallen flat. Apparently, the best line of attack the party can muster is that the president’s infrastructure bill includes spending on things that are not conventionally defined as infrastructure. Alas, this message suffers from a fatal flaw: The non-infrastructure parts of Biden’s bill are, by and large, more popular and more widely regarded as policy priorities than new spending on roads is.

For this reason, when Republicans attempt to attack Biden’s plan on this basis, they end up inadvertently helping him sell his proposal.

4) A majority of Republican House members voted to nullify the 2020 election because Democrats won it — and did this after their party’s leader had fomented an insurrection that got people killed in the halls of Congress — all of which makes it difficult for the GOP to accuse its opponents of excessive partisanship.

As far as I can tell, Republicans are right that the mainstream media is less sympathetic to their complaints of presidential partisanship than it was during the Obama years. But to the extent that this is true, it is largely a byproduct of the GOP’s own actions.

Republicans just spent four years abetting their own president’s blatant abuses of power out of crass partisan considerations (and occasionally, anonymously, confessing this sin to reporters). They then challenged the legitimacy of the 2020 election simply because their party lost. After helping Donald Trump popularize conspiracy theories that threatened our republic’s integrity — and inspired a mob to storm Congress in hopes of preempting the peaceful transfer of power — a majority of House Republicans voted to do the mob’s bidding.

Perhaps, as a result of this extremely recent history, the mainstream press no longer takes Republicans very seriously when they accuse Democrats of excessive partisanship for using budget reconciliation to pass laws (as Republicans themselves did in 2017).

5) Democrats won control of the White House and Congress, and would like to pass their agenda, which happens to be very different from the Republican agenda.

The Democratic coalition is systematically underrepresented at every level of government. To win the Electoral College in 2020, Biden had to win the two-way popular vote by nearly four points. To win control of the House in 2018, Democrats needed a historic landslide. The party only has 50 Senators, a fact that Republicans routinely invoke when arguing that Democrats lack a mandate for their agenda. And yet, because Democratic support is concentrated in high-population states like California, the party’s 50 senators represent nearly 42 million more Americans than the GOP’s.

All of which is to say: The Democrats did not secure their current trifecta by winning a narrow majority in a single election, they secured it by winning supermajorities across multiple cycles. If popular sovereignty is a sacred value — and if elections are supposed to “have consequences” — as some Republicans were wont to claim when Trump was still in office, then Democrats have every right to enact the policies that they campaigned on.

And unfortunately for conservatives and fetishists of bipartisanship, the Democratic agenda is simply very different from the Republican one. Yes, both parties recognize a need for more investment in roads and bridges. But congressional Republicans have little to no appetite for a permanent child allowance, universal prekindergarten, expanded at-home care for the elderly, or the bulk of Biden’s investments in mitigating climate change — which happened to constitute the core of his 2020 platform. Meanwhile, GOP leaders have been adamant in their opposition to both raising the corporate tax rate and deficit-financing infrastructure investment. Some Republican lawmakers have evinced interest in paying for highway improvements by hiking the gas tax or raising the minimum corporate tax rate. But it’s not clear that there is any “pay for” that ten Republican senators would all be willing to support (and that is how many GOP votes Biden would need in order to overcome a filibuster and get an infrastructure bill out of the Senate through regular order). For this reason, even if Biden were to isolate his proposal’s investments in physical infrastructure, he might still struggle to find a viable bipartisan compromise.

Ultimately, there is just a vast chasm between the Democratic Party’s vision of good government and that of the tenth-most moderate Republican in the U.S. Senate. And there is no reason why Democrats should privilege Jerry Moran’s wants and needs over those of the majority coalition that brought them to power.