Joe Biden won, but progressives lost.

For weeks after the 2020 election, this was the conventional wisdom about its outcome. As Politico wrote on November 5, “During Barack Obama’s presidency, Biden’s propensity for cutting deals with Mitch McConnell became a running source of aggravation for liberals. Now it will be the key to getting anything done at all.”

Liberals scarcely disagreed. Some histrionic progressive commentators went so far as to declare the election results a “catastrophe” for the U.S. left. Sure, Biden had evicted an authoritarian ignoramus from the White House, but his coattails had proven unrideable. The Democrats saw their House majority shrink and their hopes of taking the Senate all but collapse. Now McConnell would enjoy veto power over Biden’s entire agenda, which meant the new Democratic president would be incapable of appointing Supreme Court justices or passing any major legislation. Dreams of mining durable progressive change from the COVID crisis were dead. The only campaign promise the new president would keep was the one he had made to well-heeled donors in 2019: “Nothing would fundamentally change.”

Granted, Republicans technically hadn’t clinched a Senate majority on Election Night 2020; both of Georgia’s Senate races were headed to runoffs. But in round one, Republican incumbent David Perdue won 2 percent more votes than his Democratic challenger while coming just 0.3 percent shy of avoiding a runoff by securing an outright majority of votes. With Biden set to take office, Republican voters in the Peach State would be aching for revenge. And anyhow, even if Jon Ossoff (some millennial himbo whose chief qualification for high office was the manic delusion that he was somehow qualified for high office) managed to beat Perdue in the runoff while Raphael Warnock prevailed over Kelly Loeffler, the left’s prospects would remain basically the same: A 50-vote Senate majority reliant on Joe Manchin might enable Biden to appoint a Cabinet, but it wasn’t going to facilitate major policy change. This speculation felt so much like a settled fact that Vox’s Matt Yglesias summarized the stakes of the Georgia runoffs in mid-November thusly: “If the Democrats win, we’re going to have a functioning government, but any legislation is going to have to be substantially bipartisan.”

Georgia voters proceeded to prove the pundits wrong — and then Chuck Schumer’s majority did too. By giving Democrats full control of the federal government, Peach State voters didn’t merely secure Biden’s right to appoint an EPA director without McConnell’s consent; they also secured America the full-employment fiscal policy and universal child allowance progressives have sought for generations.

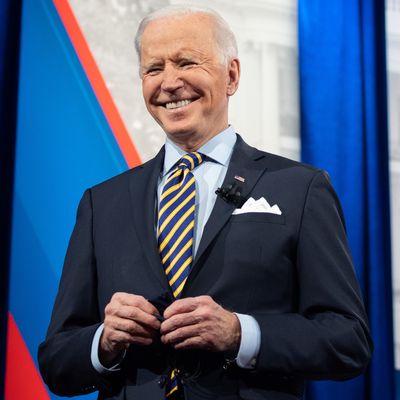

At the signing ceremony for the Affordable Care Act in 2010, Biden was famously caught on a hot mic whispering into Obama’s ear, “This is a big fucking deal.” Biden’s own American Rescue Plan is just as deserving of that title. The $1.9 trillion bill, which passed the Senate on Saturday, is a “BFD” at both the ground level and the 10,000-foot one: The legislation’s immediate policy consequences are profound and far-reaching, while its most significant provisions represent paradigm shifts in the Democratic Party’s approach to governance, which is to say the law could plausibly mark a leftward realignment in American policymaking, at least if Biden & Co. continue to govern in its spirit.

The Democratic Party’s approach to legislative strategy has fundamentally changed.

To appreciate the concrete significance of the ARP for ordinary Americans — and, by extension, the significance of having 50 Democratic votes in the Senate versus 49 — here are a few of the ways life in the U.S. is about to change as a result of a unified Democratic government coming to power:

• The average household in the bottom quintile of America’s economic ladder will see its annual income rise by more than 20 percent.

• A family of four with one working parent and one unemployed one will have $12,460 more in government benefits to help them make ends meet.

• The poorest single mothers in America will receive at least $3,000 more per child in government support, along with $1,400 for themselves and additional funds for nutritional assistance and rental aid.

• Child poverty in the U.S. will drop by half.

• More than 1 million unionized workers who were poised to lose their pensions will now receive 100 percent of their promised retirement benefits for at least the next 30 years.

• America’s Indigenous communities will receive $31.2 billion in aid, the largest investment the federal government has ever made in the country’s Native people.

• Black farmers will receive $5 billion in recompense for a century of discrimination and dispossession, a miniature reparation that will have huge consequences for individual African-American agriculturalists, many of whom will escape from debt and retain their land as a direct result of the legislation.

• The large majority of Americans who earn less than $75,000 as individuals or less than $150,000 as couples will receive a $1,400 stimulus check for themselves and another for each child or adult dependent in their care.

• America’s child-care centers will not go into bankruptcy en masse, thanks to a $39 billion investment in the nation’s care infrastructure.

• Virtually all states and municipalities in America will exit the pandemic in better fiscal health than pre-COVID, which is to say a great many layoffs of public employees and cutbacks in public services will be averted.

• No one in the United States will have to devote more than 8.5 percent of their income to paying for health insurance for at least the next two years, while ACA plans will become premium-free for a large number of low-income workers.

• America’s unemployed will not see their federal benefits lapse this weekend and will have an extra $300 to spend every week through the first week in September.

This is a small sampling of the COVID-relief bill’s consequences (more comprehensive accounts of its provisions can be found here and here). But it is sufficient to establish that something has dramatically changed in the Democrats’ approach to wielding power.

When pundits suggested progressives had little hope of getting major reform through a 50-vote Democratic majority, their speculation was well founded. After all, when Democrats had 60 votes in 2009, they struggled for more than a year to pass a watered-down version of progressives’ health-care-reform agenda, then left the bulk of their party’s constituencies with unfulfilled IOUs.

And yet: Twelve years later, with just 50 Senate votes — including one from a state Republicans won by 40 points in November — Democrats managed to pass one of the largest fiscal programs in U.S. history within weeks of Biden’s inauguration. Obama spent the better part of his first year in office seeking bipartisan buy-in for the Affordable Care Act. Biden just slapped most of his own health-care agenda on top of a $1.9 trillion relief bill and then rammed it through Congress before his administration’s two-month anniversary.

This is how progressives have been begging their party to govern for more than a decade: Ignore the Beltway’s fetish for bipartisanship and deliver big, clear gains to the American people. The Democratic leadership has now affirmed that counsel in both word and deed. As Schumer told the Washington Post this week, “What happened in 2009 and ’10 is we tried to work with the Republicans, the package ended up being much too small, and the recession lasted for five years. People got sour; we lost the election.”

Democrats (finally) abandoned the policy of starving America’s poorest children to punish their jobless parents.

The American Rescue Plan reflects a similar leftward revision in the party’s approach to social welfare.

For a quarter-century, whenever Democrats proposed new safety-net programs, they filled them with holes large enough for the very poorest to fall through.

In response to the Reaganite backlash against the urban poor in general and mythical “welfare queens” in particular, the party decided the only politically viable way to raise the living standards of low-income Americans was to condition federal aid on labor-force participation. Thus, the various tax credits the party has used to mitigate child poverty over the past two decades have all included phase-ins that require recipients to earn a certain amount of labor-market income to qualify for help. For example, as of last year, the poorest 10 percent of U.S. parents were ineligible for the child tax credit because they made too little to qualify.

From the day Bill Clinton ended welfare as we knew it, progressives have been decrying the senseless cruelty of this policy: Using child poverty as a tool for promoting work wasn’t just morally reprehensible but self-defeating. Giving unconditional cash assistance to poor families makes their children more likely to hold full-time jobs as adults.

Many Democratic lawmakers had already embraced this viewpoint before the pandemic. And through the CARES Act, they were able to break the taboo against providing unconditional cash assistance to the poor. Now, the ARP has made revisions to the child tax credit that turn it into a de facto child allowance: Virtually all U.S. parents will receive a $3,600 payment from the government for each child age 5 and under and $3,000 for each kid between the ages of 6 and 17. These payments will be dispensed in periodic installments, functioning less like a tax credit than a basic-income program.

For now, these changes to the CTC are set to expire after a single year. But Democratic leaders intend to make the program permanent. (The apparent strategic logic of making it temporary goes like this: Making the child allowance permanent in the relief bill would have pushed its price tag above $2 trillion, thereby endangering moderate support. But once moderates are faced with a choice between voting for an expensive extension of the policy and allowing every family in America to simultaneously see their disposable income shrink right before a midterm election, they will rally behind “big government.”) Should that happen, the U.S. would finally join the rest of the wealthy world in compensating all of its parents for the socially necessary labor of raising the next generation.

The Democrats’ fiscal philosophy is now apparently “There is nothing to fear but fear of deficits itself.”

The Democratic Party hasn’t just internalized the left’s critique of its legislative strategy under Obama or its social-welfare policies under Clinton, but also its conception of macroeconomics since Jimmy Carter.

When Obama’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act passed in 2009, the official U.S. unemployment rate stood at 8.1 percent. Average household wealth in the country had just plunged. The global financial system had gone shaky at the knees. Meanwhile, the U.S. national debt was $9 trillion, and a Senate led by a filibusterproof Democratic majority opted to pass a grand total of $787 billion of stimulus to avoid running up the federal deficit.

Today, the official unemployment rate is 6.2 percent, most U.S. households are better off financially than they were before the pandemic, stock prices are hovering near record highs, the national debt sits at over $28 trillion, and — even though Congress has already spent nearly $3 trillion fighting the current economic downturn — a single-vote Democratic Senate majority just passed $1.9 trillion in fiscal relief.

This constitutes a sea change in Democratic fiscal orthodoxy. As the party’s erstwhile economic guru Larry Summers has lamented, the ARP is not a conventional stimulus plan. It does not merely seek to fill the hole in consumer demand that the pandemic opened up; rather, it aims to leave a modest mountain where that hole used to be. The point is to accelerate the restoration of February 2020’s labor-market conditions — and then drastically improve upon them. Put differently, the Democratic Party has decided to prioritize the maximization of employment over the minimization of inflation risk.

For most of the past four decades, American policy-makers have set the opposite priority. When consumer demand is high and labor markets are tight, it is difficult for employers to replace their existing workers with unemployed ones. For this reason, in a “full employment” economy, workers can generally extract higher wages from their bosses through the implicit or explicit threat of quitting. And when workers win wage increases, employers sometimes respond by raising prices. Following the “stagflation” crisis of the late 1970s, America’s fiscal and monetary authorities decided that preempting price hikes was so much more important than promoting full employment that they had a duty to keep millions of Americans involuntarily unemployed at all times, lest labor secure too much leverage over capital. As recently as 2015, Democratic Fed chair Janet Yellen began raising interest rates to deliberately “cool off” the economy and slow job growth because all serious policy wonks believed that if the unemployment rate fell below 4 percent, runaway inflation would ensue.

For roughly 40 years, progressives have been protesting the macroeconomic orthodoxy that the social and economic benefits of maximizing employment are dwarfed by the harms of a hypothetical spike in inflation as being both morally unacceptable and empirically unfounded. And anyhow, the risk of runaway price increases has been perenially overestimated. Meanwhile, left-wing economists were pleading with Democratic deficit scolds to cease sacrificing GDP growth on the altar of their own fiscal illiteracy.

With the ARP, the Democratic Party has affirmed its advice in word and deed. As the president said in February, tacitly rebuking Summers, “The risk isn’t that we do too much when it comes to a COVID-relief package — it’s that we don’t do enough.”

None of this means progressives should be wholly satisfied with the first major law of the Biden era or the party that produced it. On Friday, eight Democratic senators voted against adding a $15 minimum-wage amendment to the COVID-relief bill, despite the fact that the policy commands supermajority support across the U.S. and that $15 is far lower than the minimum wage would have been had wages kept pace with productivity growth over the past 40 years. The Democratic Party’s appetite for increasing labor’s leverage over capital remains grossly inadequate to the demands of economic justice. Meanwhile, many of the relief bill’s best provisions, including its $300 federal unemployment benefits, are poised to phase out by year’s end. The ARP will erect an impressive pop-up welfare state, but America deserves the real thing.

That the Biden presidency has already exceeded many progressives’ (low) expectations is not cause for contentment; it is grounds for progressives to raise their expectations. Some things can fundamentally change.