Last week, fewer Americans applied for unemployment benefits than at any time since March 2020. Last month, retail sales in the U.S. rose by 9.8 percent, the largest increase in nearly a year. Factory activity in the state of New York just hit its highest level since 2017; in Philadelphia, manufacturers are now more confident about business conditions than they have been since 1973. As of this writing, U.S. stock values have hit an all-time high. All of this news is better than expected. And yet the yield on U.S. Treasury bonds declined Thursday morning — a sign that global investors believe America can have its post-COVID economic boom and its low inflation, too.

In other words, it’s a good morning for “Bidenomics.”

Economists surveyed by Bloomberg had projected a 5.8 percent jump in retail sales in March, but the combined effect of the American Rescue Plan’s $1,400 stimulus checks, strong job growth, and rising vaccination rates provided a more potent boost to commerce than experts had foreseen. The rebound was especially strong at restaurants and apparel retailers, which saw 13.4 percent and 18.3 percent increases in overall sales values, respectively. But the surge wasn’t limited to sectors hampered by the pandemic; furniture outlets, e-commerce shops, and other businesses that thrived throughout the COVID crisis still enjoyed an uptick in revenues last month.

The picture on jobless claims is also positive, if less comprehensively so. Economists had expected about 700,000 Americans to file for first-time unemployment benefits last week; instead, 576,00 did. That’s down nearly 200,000 from the preceding week and suggests the economy is adding far more jobs than it is shedding. Nevertheless, over half a million Americans filing jobless claims in a week would not have qualified as good news before the pandemic.

Taken together, Thursday’s data paints a sunny picture for the American economy in 2021. The $1.9 trillion relief bill Democrats enacted last month appears to be working as intended — accelerating a return to full employment by increasing consumer purchasing power without dampening investor demand for U.S. government debt or raising long-term inflation expectations.

How durable the “Biden boom” will be is an open question. CNBC’s Jeff Cox argues that “the economy is running on a stimulus-fueled caffeine high” and that deepening inequality and inflationary risk could stymie growth once the $1,400 checks are spent. But this frame seems misguided. Without question, the U.S. economy suffered from structural defects even before the pandemic — tepid working-class wage growth, inadequate housing, a parasitic health-care sector, low business investment, and an ecologically unsustainable energy system — and the COVID crisis will leave lasting scars on America’s labor market. There is little reason to believe, however, that consumer demand will decline precipitously any time soon.

For one thing, fiscal support (probably) isn’t going anywhere. Another round of $1,400 checks isn’t in the offing, but Biden’s child allowance will take effect in July, at which point virtually every family in the country will receive at least $250 per kid, every month, from Uncle Sam. Those checks are set to expire at year’s end, but Biden has called for the policy to be extended through 2025 and congressional Democrats appear likely to oblige this request. What’s more, much of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan funds have yet to be spent and will enter the economy in the years to come; to take one example, many state governments will use their newfound federal aid to bankroll school construction and infrastructure improvements. Meanwhile, a multi-trillion-dollar federal infrastructure package is also likely to pass by year’s end. As proposed by the White House, such legislation would take effect gradually over a period of eight years.

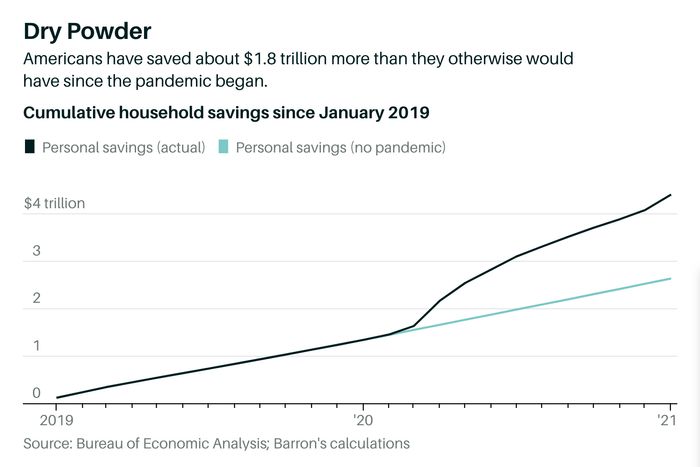

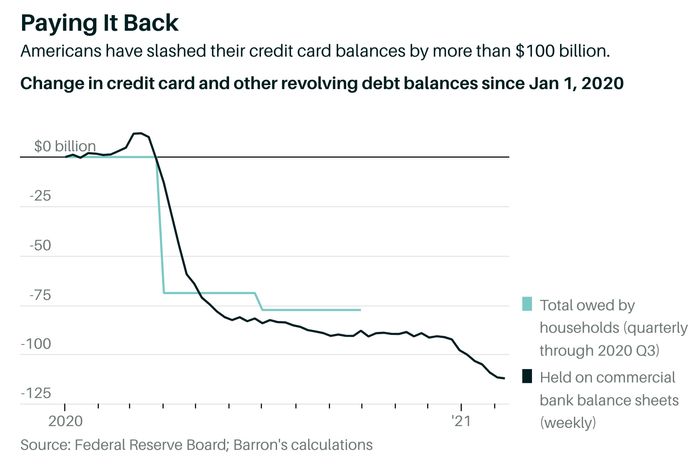

For another thing, although an unfortunate minority of Americans have been devastated by the pandemic, most U.S. households are better off financially today than they were before COVID reached our shores. The combination of multiple rounds of stimulus checks and a pandemic-induced contraction in consumption opportunities has enabled Americans to pay off old credit-card debts and stockpile savings.

After the 2008 crisis, recovery was hampered by weak household balance sheets; the housing bust and financial crisis took a bite out of the median American’s net worth. But the COVID crisis has paradoxically increased household wealth. And as the economy fully reopens and unemployment falls, more of those pent-up savings will find their way into cash registers (or the digital equivalent).

This said, the U.S. still has a ways to go before eradicating its public-health crisis, and widespread vaccine hesitancy remains a formidable obstacle. Meanwhile, the pandemic has done lasting damage to the economic, social, and political fabric of nations the world over, and the second- and third-order consequences of that damage are impossible to fully anticipate. If the past year has taught us anything, it’s that catastrophic contingencies in faraway countries can ripple across oceans and derail our economy. And in the Anthropocene, catastrophic contingencies are a growth industry. If Democrats supply further fiscal support, pass major climate legislation, fortify global public health and pandemic prevention — and we all get very lucky — this century may witness a “roaring ’20s” that isn’t followed by globe-spanning mass murder.

If not, well, we should at least have an economically vibrant “white boy summer.”