Ever since it entered the popular lexicon last year, the motto “defund the police” has been given an almost mystical power.

For Representative Jim Clyburn, it crushed U.S. Senate hopeful Jaime Harrison’s 2020 bid to unseat Lindsey Graham in South Carolina, even though the Democrat never endorsed it and was already trailing in most preelection polls in a state that Donald Trump won by 12 points. For William Bratton, the former Los Angeles and New York City police chief, it had dire consequences when it was put into action. “They got what they wanted,” Bratton told the New York Times last month. “They defunded the police. What do they get? Rising crime, cops leaving in droves, difficulty recruiting.” Never mind that “defunded” doesn’t accurately describe what happened to the cops in New York — it was more like short-term budget reshuffling with creative marketing — and that rising violence was as bad or worse in large cities across the country, regardless of whether police got less money than the year before.

For Barack Obama, using the phrase undermines reform because it’s alienating. (Its originators — police abolitionists — are, in fact, openly uninterested in reform.) And for many pundits and political reporters, this month’s Democratic mayoral primary in New York City was a de facto referendum on the issue.

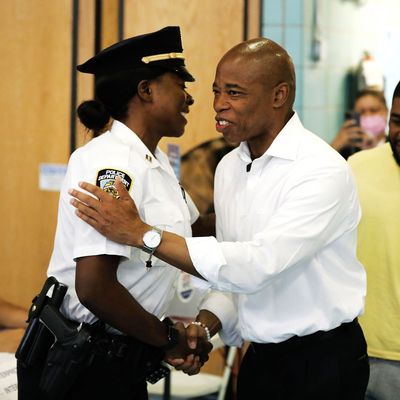

The results are in. Eric Adams, the former police officer turned Brooklyn borough president, has a commanding lead — though not an insurmountable one — after the first tally of ranked-choice votes on Tuesday, winning a 32 percent plurality. His closest challengers, Maya Wiley and Kathryn Garcia, trail him by ten and 13 points, respectively, and the longtime front-runner in preelection polling, Andrew Yang, has already conceded, with 100,000 absentee ballots yet to be counted. It’s not over, but it looks like Adams has the biggest coalition — a sad but not unexpected development for the city’s insurgent left, which produced Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in 2018 but has yet to achieve anything like a governing mandate locally, despite making inroads in the offices of comptroller, public advocate, and on the City Council.

Early on, Adams made it clear that he was against defunding the police. The takeaway, as far as this supposedly determinative issue is concerned, looks self-evident: “Defund the police” is a campaign killer in New York City, where very few actual people want it to happen, just like it ruined Harrison’s chances in South Carolina, stalled reasonable reform efforts in other cities, and plunged the Big Apple under a rising tide of blood.

One problem with interpreting the race as a referendum on “defund the police” is that only one of the candidates, Dianne Morales, actually committed to doing so as mayor, and her campaign has been dead in the water for weeks because of her union-busting and general mismanagement. Even those who have supported the idea in the past, like Scott Stringer and Wiley, have softened their rhetoric since declaring their candidacies and avoided mentioning it in their campaign platforms and materials. Much as “defund” did during the 2020 election, when it was used by Republicans as a smear against Democrats, the proposal has functioned here more as insinuation than actual menu item.

A related problem is that the phrase has been deployed as a catchall for a range of often conflicting ideas and policies. Some activists mean its original usage as a step toward police and prison abolition. Others have freighted it with their own idiosyncratic definitions, like Washington, D.C., mayor Muriel Bowser, who has claimed it really means “good policing.” Combine these muddled conceptions with the expected caricaturing and fearmongering by its detractors, and it’s not shocking that “defund” has framed so much election punditry: Its flexibility makes it a convenient vehicle for all kinds of questionable ideological claims.

Adams’s success probably has less to do with his stance on defunding the police, which almost none of his opponents supported either, than with being a skilled and opportunistic politician who performed well for the same reasons that most opportunistic politicians do. As for what this race reveals about the viability of defunding as a political proposal, it’s hard to say when its primary feature was its absence. We’re left with what we’ve known all along: Politicians tend to avoid unpopular stances, and activists tend to embrace them despite their unpopularity.

This may very well be a revelation to some aspiring progressive champion seeking higher office and will cause them to rethink putting “defund the police” at the center of their future vote-getting strategies. But the more practical lesson of Adams’s triumph is that it’s still useful to be the guy willing to say whatever it takes to accrue power and influence.

Adams’s history with his former employer, the New York Police Department, was fraught from the outset. He joined in the early 1980s and promptly advertised his ambivalence toward the whole endeavor, earning a reputation as an outspoken critic of police racism, both toward civilians and the department’s own Black officers. His feelings derived, in part, from his own experiences as a child, when cops assaulted him and his brother inside a Queens police station. He joined the force to “just aggravate people,” he said, and spoke out against stop and frisk in the 1990s, putting him at odds with then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani. (Giuliani, now Trump’s personal lawyer, currently wants Adams to win the primary. “There’s no question that Adams gives us some hope,” he said earlier this week.)

Tensions were high enough between Adams and his superiors during the 1980s and ’90s that several of his contemporaries say it probably impeded his career advancement within the NYPD and motivated periodic investigations into his conduct. Colleagues have also said this wasn’t a major concern for him, and in fact might have been the point: Adams ran unsuccessfully for Congress at age 33, just ten years after becoming a cop, and was widely seen as treating the department and his crusade against its abuses as stepping-stones to a life in politics.

His tune has shifted. With rising rates of gun violence and homicides topping New Yorkers’ priorities ahead of the election, Adams has represented himself as a more traditional tough-on-crime candidate, trumpeting his law-enforcement bona fides and expressing qualified support for stop and frisk. A policing career once marked by antagonism and clashes with higher-ups has, paradoxically, seeded within him a love for the profession, he says. “I don’t hate police departments — I hate abusive policing, and that’s what people mix up,” Adams told the New York Times. “When you love something, you’re going to critique it and make it what it ought to be.”

This incongruity isn’t proof per se that he’s insincere, but from his time as a cop through his tenure in the state legislature, Adams’s colleagues have regularly attributed to him a “penchant for self-promotion,” “blunt-force ambition,” and a tendency to look out for himself and his career above all else, according to the Times. “He just wasn’t a team player,” a senior State Senate aide told New York’s David Freedlander. “In a way, that’s true for everybody in politics, but you always got the sense that the thing Eric Adams cared most about was what was in it for Eric Adams.”

The implications of this accusation are evident in some of his recent behavior. In an interview with Mishpacha, Adams proclaimed his “love” of Israel by saying he wanted to retire to the Golan Heights, a contested region of Israeli-occupied Syria. As New York’s Eric Levitz writes, he has also continued his long-standing habit of using baseless allegations of racism to deflect criticism and remove impediments to amassing power, comparing Yang’s last-ditch decision to campaign with Garcia to Jim Crow–era poll taxes and saying it sent a message that “we can’t trust a person of color to be the mayor of the City of New York.”

Adams’s attitude toward policing has been a roller coaster of dissonant sentiments, but his knack for advancing his own political ambitions, and willingness to say whatever was required to do so, have been consistent. Along with his ability to build a demographically fortuitous coalition of voters — a mix of “labor unions, Black homeowners, real-estate interests, and other Democratic Party politicians” that could make him “one of the most powerful mayors New York has had in a generation,” according to Yale law professor and New York elections expert David Schleicher — he’s on the verge of his most successful application of this formula yet.

It may indeed be politically perilous to support defunding the police. Most of the candidates are operating from this belief. The irony of casting Adams’s success as a death knell for “defund,” however, aside from being dubious, is that there’s still an appetite for police reform among New Yorkers, and his election is poised to be one of the most impervious obstacles to shaking up status quo law enforcement, inviting much of the same violence that got people into the streets last summer. Adams has benefited from the same craven political principles that have built winning campaigns for generations. The people of New York will be rewarded with more of what those principles have always gotten them.