J.D. Vance is running for Congress as a conservative Republican — and stalwart enemy of “the ruling class.”

With Rob Portman poised to retire next year, a not-so-diverse array of reactionary Ohioans is vying to fill the Republican senator’s seat come 2023. But Vance has a plan to distinguish himself from the crowd: The venture-capital executive and best-selling memoirist is running as an unabashed right-wing populist, one who weds bog-standard GOP critiques of the cultural elite to an (ill-defined) indictment of contemporary capitalism.

Hours after his campaign launch last Thursday, Vance described his candidacy’s fundamental premise to Tucker Carlson. “You have elites and the ruling class that have plundered this country, that have made it harder for middle-class Americans to live a normal life,” Vance told his fellow self-styled populist. “And when those Americans dare to complain about the conditions of their own country, if they dare to complain about the southern border or about jobs getting shipped overseas, what do they get called? They get called racists, they get called bigots, xenophobes, or idiots.”

To which Carlson replied, “I love it.”

The Fox News host’s ardor is understandable. Vance’s broadsides against free trade and undertaxed multinationals echo those made by Carlson in recent years. In 2019, he denounced his party’s “market fundamentalism” and decried the fact that “an American who works for a salary pays about twice the tax rate as someone who’s living off inherited money.”

What’s more, Vance’s populism isn’t entirely rhetorical. In his opening campaign ad, the Republican vows to raise taxes on “multinational companies” that are shipping jobs overseas.

Vance’s bid for Senate remains a long shot. But the fact that he has chosen to campaign against “the ruling class” — and for higher taxes on footloose corporations — has led some to view Vance as a harbinger for the coming hegemony of a pro-worker conservatism.

But he (almost certainly) isn’t.

The sincerity of Vance’s populism is belied by the identities of his chief bankrollers: Peter Thiel, the pro-Trump Silicon Valley oligarch who despises elite rule so much that he wants to abolish democracy, and the Mercers, a family of hedge-fund billionaires who despise progressive redistribution. Further discrediting Vance’s populist pretensions is his refusal to endorse Joe Biden’s proposal for raising the corporate tax rate. Right now on Capitol Hill, there is an active political fight over whether to raise taxes on multinationals and those “living off inherited money.” Yet despite their avowed interest in soaking such “elites,” Vance and Carlson have declined to lambaste Republicans and moderate Democrats for opposing such measures. Nor, for that matter, did they criticize Donald Trump for opposing Biden’s tax plan — on the grounds that raising taxes on corporations would only chase them overseas.

The Trump presidency yielded real change in the class composition of the Republican electorate; red America has grown more blue collar. But as of yet, there is little evidence that Trump has effected any major change in the GOP’s class allegiances. And this is not merely because the “Tucker Carlson wing” of the party has yet to oust the old Establishment. It’s also because that populist wing is itself hostile to the working class.

Carlson and Vance aren’t doctrinaire free marketeers. And this makes them ideologically distinct from their Reaganite forebears (not to mention their own previous personae). Nevertheless, their brand of populism doesn’t serve the little guy so much as the small-time rich — a contingent that extends all the way from the highest ranks of the labor aristocracy (six-figure-earning skilled tradesmen with paid-off mortgages) to the lower tier of the plutocracy (provincial multimillionaires whose cultural mores alienate them from the cosmopolitan Über-elite). It is a politics of cultural animus of, by, and for reactionaries in the top 20 percent of wealth distribution (but primarily for those in the top one percent).

Thus, in its class loyalties, the “Tucker Carlson right” is largely indistinct from the pre-Trump GOP. The populist right is marginally less beholden to multinational firms but is no more concerned with the plight of the working poor. Like Reaganism before it, Carlsonism exists to rationalize the power and privilege of the economic elite and to hoodwink working people into mistaking that elite’s causes for their own. The Fox News host and his acolytes just take a different approach to these tasks: Whereas Reaganism sanctified the plutocracy’s prerogatives with hypocritical hosannas to the “free market,” Carlsonism does so via hypocritical attacks on the plutocracy, or rather, on small segments of the plutocracy. The populist right’s signature rhetorical trick is to scapegoat a few multinational firms for social problems that its own primary constituency — reactionary, small-time rich people — are committed to exacerbating.

Carlson, Vance & Co. marry this selective anti-corporate demagoguery to the conservative movement’s perennial rhetorical gambits, including appeals to white racial resentment and apocalyptic warnings of creeping communism. Today’s right-wing populists are even more dependent on such rhetorical devices than the GOP of yesteryear was because Carlsonism consists of little else. Beneath Carlson’s evasions and misdirections, there is no coherent philosophy of government for his ideological allies to betray. It is ad hoc rationalizations for elite privilege all the way down.

But don’t take my word for it, take Tucker’s.

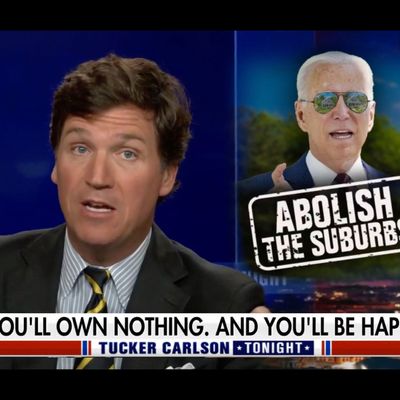

Days before hosting Vance, Carlson delivered a jeremiad against the Biden administration’s nefarious plot to “abolish the suburbs.” Of course, Uncle Joe isn’t actually planning to liquidate the kulaks of Panera Land. Rather, the White House has partially restored an Obama-era rule requiring municipalities to take affirmative steps toward racial integration in order to qualify for federal grants. In some contexts, this means that affluent, white suburbs must tolerate the construction of apartment buildings so that disproportionately nonwhite, working-class families can afford to live among them (and to avail themselves of well-funded school systems and municipal resources).

It was this prospect — of suburbs being forced to accept a slightly freer market in housing construction — that raised Carlson’s hackles. Democrats want to force suburban homeowners to tolerate “more hi-rise apartment buildings, maybe some drug-addicted vagrants living on the sidewalk, begging for change,” the pundit warned. He applauded the liberals of Westchester for standing their ground against federal efforts to expand their county’s housing stock, but he lamented that, “under pressure from federal ideologues, communities in Oregon and Minneapolis, for example, have abolished single-family zoning in recent years.”

Carlson’s ensuing diatribe epitomizes the politics of the populist right.

What makes his defense of single-family zoning so instructive is that it’s both anti-free-market and anti-working-class. Carlson is defending the right of local governments to prohibit a large category of commerce: There are private firms that would like to build apartment buildings in Westchester and consumers who would like to purchase or rent homes in that area. But the (municipal) government is forbidding these parties from engaging in such mutually beneficial exchange.

Of course, right-wing populists don’t claim to regard free markets as sacrosanct; rather, they tout their willingness to subordinate free markets to the interests of working people. But Carlson’s defense of single-family zoning is no such thing. The cumulative consequence of local governments mandating single-family housing — along with myriad other zoning restrictions — is a massive housing shortage. According to a recent analysis from the mortgage-finance organization Freddie Mac, America is 3.8 million housing units short of buyer demand. This artificial scarcity benefits some. As demand for housing outstrips supply, those who own homes in desirable areas see their net worths rise.

But for the downtrodden “forgotten men and women” whom right-wing populists claim to champion, single-family zoning is actually a scourge. It prevents homeowners in economically depressed regions from affordably relocating to thriving metros. And it forces renters to forfeit an ever-higher share of their income to landlords. Between 2001 and 2017, the share of U.S. renters who were cost-burdened — meaning they devoted more than 30 percent of their income to rent — rose from 42 to 48 percent. The main cause of this development was simple: The number of rental households in the U.S. grew at a faster rate than the supply of rental units did. The failure of supply to keep up with demand was partly attributable to “zoning and land-use regulations that can prohibit or increase costs for new rental units,” according to the Government Accountability Office.

Viewed from the perspective of society as a whole, single-family zoning is ruinous. According to a 2017 study from economists at the University of Chicago and UC Berkeley, land-use restrictions have reduced U.S. gross domestic product by 50 percent over the past half-century and thereby cost the average American worker roughly $6,775 in income each year.

Thus, Carlson’s position is that allowing affluent homeowners to keep working-class people out of their neighborhoods and schools — through restrictions on free commerce — should take precedence over both meeting the broader public’s housing needs and maximizing the nation’s overall prosperity. Put differently: It is an assertion of a privileged social class’s absolute entitlement to hoard resources irrespective of the implications that has for the common good.

Neither market fundamentalism nor any coherent theory of populist nationalism could justify such a stance. Carlson’s defense of single-family zoning has no sturdy philosophical grounding. It rests on aggrieved entitlement alone.

To obfuscate the true nature of his argument, Carlson has marshaled the populist right’s full panoply of demagogic diversions. He has cast this as a conflict between race-obsessed bureaucrats and sensible Americans. To do this, he (1) focused exclusively on the White House’s efforts to promote upzoning through enforcement of the Fair Housing Act and then (2) misrepresented claims about the historical determinants of racial inequality as allegations of racial prejudice.

The rise of the suburbs in the mid-20th century was, in fact, shaped by state-sponsored racism. The Federal Housing Administration promoted suburban development by giving preferential treatment to loans on single-family housing outside urban centers. And it promoted racially segregated suburbs by choking off mortgage insurance to neighborhoods with significant African American populations. In 1955, the great urban planner Charles Abrams argued that the FHA had “adopted a racial policy that could well have been culled from the Nuremberg laws.”

The Fair Housing Act empowers the federal government to redress this historic injustice by using its grant programs to promote integration. The aim of the law wasn’t merely to forbid discrimination in housing markets, according to its co-sponsor Walter Mondale, but to ensure the replacement of “ghettos by ‘truly integrated and balanced living patterns.’” And zoning restrictions in predominantly white, affluent suburbs of heavily nonwhite cities are a major obstacle to that aim.

Carlson, of course, elides all of this context to make it sound as if the White House’s policy is premised on the claim that the very existence of concentrated Black poverty proves white suburbanites are personally racist:

According to [former HUD secretary Julián] Castro, the existence of “concentrated poverty” in urban centers — as opposed to suburbs — constituted de facto evidence of racial discrimination. In other words, as long as there is a place that is poorer than the place you live, then the place you live is racist.

Carlson further conceals the class implications of his position by portraying its opponents as a quasi-totalitarian threat to ordinary Americans’ political freedom. He explains that the Democratic Party aims to abolish the suburbs — even though it knows this means destroying “the lives of people who live in nice places” — because it is indifferent to policy outcomes. Its only goal is to build “a one-party state.” And since Democrats dominate electoral politics in cities, they’re trying to turn every region of the country into a city.

This argument is so preposterous as to scarcely merit refutation. But note the histrionic sense of entitlement that underlies it: Contrary to Carlson’s evocative language, no one is proposing the mass demolition of existing single-family homes; no one is trying to tell suburbanites what they can and can’t do on land they personally own. Rather, progressives are asking suburban homeowners to cease blocking housing construction on land they do not own (or else forfeit a portion of their municipality’s federal subsidies). This is what Carlson describes as an attempt to destroy suburbanites’ lives.

Finally, Carlson showcases his contingent’s signature piece of rhetorical misdirection. “If you wanted to fix the affordable-housing crisis,” he muses, “maybe you would prevent foreign governments from buying up residential housing, which they are doing, or BlackRock from buying up single-family homes and turning them into rentals.” But Democrats are doing neither of those things, and therefore, their housing agenda’s official aims are plainly fraudulent.

Alas, neither foreign governments nor multinational investment firms have much to do with the crisis of housing affordability. BlackRock is an asset manager with minuscule investments in residential real-estate. The firm owns about $60 billion in real-estate assets; the total value of U.S. rental housing in 2020 was $4.5 trillion. Notably, even the tiny portion of U.S. real estate that BlackRock “owns” is, at bottom, owned by Americans in the same general social class as the typical direct homebuyer in an affluent suburb. (If you have a 401k account, there is a decent chance that you own shares in a fund that owns shares of residential housing.)

Whatever one makes of institutional investors entering the real-estate market, it simply is not a large enough phenomenon to explain the scarcity of affordable housing in the U.S. But the adoption of single-family zoning — which is to say, laws that aim to keep housing units scarce within a given jurisdiction — is widespread enough to explain the problem.

For Carlson’s true constituents, housing unaffordability is the opposite of a problem. For the small-time rich — affluent suburban homeowners, for example — high housing prices are a synonym for high personal wealth. Late in his monologue, Carlson betrays this fact:

For multinational corporations like Black Rock, the point is driving down the costs of homes even further and building more apartment high-rises in the suburbs. That’s been the goal of the most powerful people in the world for some time. [emphasis mine]

One minute, Carlson casts BlackRock as the cause of the affordable-housing crisis; the next, he explains that the firm’s nefarious mission is to make housing cheap. He is speaking to genuine economic anxieties, but they are the anxieties of precariously wealthy homeowners who jealously guard their financial, geographic, and psychic distance from the lower orders.

Carlsonism is a politics of downward-looking class resentment disguised as its opposite. Faced with an instance in which the liberal, coastal elite is genuinely betraying the working class, Carlson rallies to the libs’ side.

To be sure, one can’t indict any political tendency on the basis of a single monologue from a cable-news host. But this era’s self-styled populist conservatives have consistently demonstrated their fealty to small-time capitalists — and contempt for the median laborer — in just about every major policy fight of Biden’s tenure. Carlson’s call for higher housing costs isn’t an exceptional betrayal of the populist right’s putative class allegiance, only an exceptionally naked one.