If the phrase had less sordid connotations, a decent two-word summary of Joe Biden’s case for leaving Afghanistan would be, “America first.”

In a eulogy for that conflict Tuesday, Biden declared an end to the “era of major military operations to remake other countries.” He argued that America’s fundamental error in Afghanistan had been allowing a counterterrorism mission to morph into a quixotic nation-building exercise. He challenged “those asking for a third decade of war in Afghanistan” to name a single “vital national interest” that the U.S. has in occupying that nation. And he vowed not “to send another generation of America’s sons and daughters” to fight for the dream of “a democratic, cohesive, and united Afghanistan — something that has never been done over many centuries of Afghans’ history.”

If Biden defends the U.S. withdrawal on nationalist grounds, many of his detractors condemn the policy on similar ones.

Pundits have lamented America’s retreat from Afghanistan as a consolidation of the Trumpist turn in its foreign policy. Biden may have “campaigned on bringing America back to its position as a leader of the free world and as a champion for human rights,” Josh Rogin recently wrote for the Washington Post, but the president has now subordinated Afghans’ democratic freedom to a “cold, national interest calculation.” Foreign correspondents have conveyed this same critique through both heartrending reports of Kabul residents’ plight and tacit condemnations of the American president’s (and/or public’s) seeming indifference to the same.

There is something to their case. Two weeks ago, in his first speech after Kabul’s fall, Biden really did coat the bitter pill of defeat in a layer of saccharine chauvinism, saying of the Afghan security forces, “We gave them every chance to determine their own future. What we could not provide them was the will to fight for that future.” And the American public really is parochial. Until recently, news consumers’ interest in the Afghanistan war was minuscule; last year, it attracted five minutes of total coverage across the three major networks’ evening newscasts. The U.S. electorate has also been less than reliable in its support for foreign aid or mass refugee admissions. Our collective antipathy for thinking poorly of our own nation often leads us to victim-blaming accounts of our imperial misadventures — e.g., “Afghans just weren’t ready for democracy.” For reporters stationed in Kabul, who are intimately acquainted with the strata of Afghan society that thirsts for a liberal republic, such sentiments surely grate.

Yet American parochialism does not stop at the water’s edge. The typical U.S. citizen might be unable to locate Afghanistan on a map, but those who led the U.S. war effort overseas were little better at recognizing that same country through the fog of their imperial fantasies. Many American generals felt no need to acquaint themselves with Afghanistan’s most basic ethnic tensions before formulating counterinsurgency campaigns. In 2003, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld confessed to the Pentagon that he had “no visibility into who the bad guys are in Afghanistan.” His childish diction was indicative of America’s broad mentality toward the conflict. The war was neither sold nor conceived in coolheaded strategic terms so much as mythopoetic ones. Afghanistan was a blank screen on which Americans could project everything they feared in 9/11’s wake. Or else, it was a theater for staging a revival of our nation’s most flattering mythic struggles: The NATO coalition would be our generation’s Allied forces. We would bring democracy to Kabul just as we had to Berlin.

Perhaps, $2 trillion would have been enough to buy Afghanistan a stable, pluralist government if we had paid attention to the country’s idiosyncrasies. But we didn’t do that because we didn’t care to. We weren’t interested in seeing Afghanistan clearly. We were interested in killing terrorists; securing a bastion of U.S. power in central Asia; stimulating a McMansion boom in Arlington, Virginia; dissolving 9/11’s traumas in a great martial psychodrama; and re-baptizing our decadent nation in the blood of Afghans. We were interested, in other words, in putting America first.

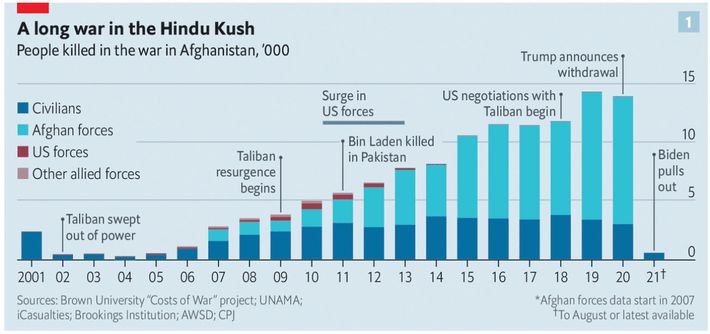

Indeed, even as they denounce Biden for indulging in myopic nationalism, many critics of his withdrawal have themselves placed America’s national self-esteem above the typical Afghan’s well-being. This is reflected in their refusal to grapple with the human costs of the U.S. prolonging Afghanistan’s civil war. The extraordinary speed of the Taliban’s takeover has been described, almost universally, as a “humiliation” for our country and scandal for the Biden White House. And yet, from the perspective of ordinary Afghans, a rapid Taliban victory was far preferable to the alternative: Our intelligence agencies long ago concluded that the U.S.-aligned government in Kabul could not stand on its own and, at best, they expected Afghanistan’s fledgling democracy to hold off the Taliban for a few years after America departed. Such an interval would have secured the United States some plausible deniability (“we left the Afghans a functioning republic, it’s not our fault if they couldn’t keep it”). And it would have spared our nation some of the trauma of defeat: By the time Taliban fighters marched into Kabul, Afghanistan would no longer be a subject fit for primetime news. But this more successful version of American withdrawal would have also increased the ultimate death toll of the Afghanistan war by tens of thousands, for no higher purpose beyond delaying the inevitable.

The press’s endemic disregard for the human costs of perpetuating a military stalemate can be seen in Peter Baker’s most recent “news analysis.” The New York Times reporter has been tacitly editorializing against Biden’s withdrawal for weeks. On Saturday, he offered his most straightforward critique of the president’s policy yet in a piece headlined “All in or All Out? Biden Saw No Middle Ground in Afghanistan.” Baker’s argument is that a middle-ground option did exist, and that Biden’s failure to occupy it is lamentable. As a news analyst — not an opinion writer — Baker is unable to make this point forthrightly. Instead, he launders it through quotations like this one from retired general David Petraeus:

“There was an alternative that could have prevented further erosion and likely enabled us to roll back some of the Taliban gains in recent years,” said Gen. David H. Petraeus, the retired commander of American forces in Afghanistan and former C.I.A. director who argued the mission was making progress while serving alongside Mr. Biden under President Barack Obama.

“With the Afghans doing the fighting on the front lines and the U.S. providing assistance from the air,” he added, “such a force posture would have been quite sustainable in terms of the expenditure of blood and treasure.”

Here, Petraeus argues that, contra Biden, the status-quo ante could have been maintained at a sustainable cost in “blood and treasure” — because Afghans would have done the frontline fighting (and thus, the bulk of the bleeding). In other words, Petraeus is arguing that if we’d sent thousands of Afghan troops to slaughter each year until the end of time, we probably could have propped up a deeply corrupt Western-aligned government in some parts of Afghanistan indefinitely. This case is dubious on the merits (the Taliban had been making steady gains since the late Obama years, when troop levels were much higher than they’d been at the time of Biden’s inauguration). But it’s also rather bleak in its substance. That neither Petraeus nor Baker feel compelled to note the tragic dimension of the former’s proposal indicates how much more weight they give to the costs of American defeat than to those of Afghan civil war.

All this said, going forward, putting Afghans first will likely require opposing White House policy. Amid his many appeals to geopolitical realism Tuesday, Biden did reiterate his commitment to putting “human rights” at “the center of our foreign policy.” The way to do this, he continued, “is not through endless military deployments, but through diplomacy, economic tools, and rallying the rest of the world for support.”

In the context of a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, the phrase “economic tools” has an air of menace. Afghanistan was a desperately poor nation before its government collapsed and its currency depreciated. Today, it is teetering on the precipice of famine. As the economic historian Adam Tooze explains in a recent newsletter, over the course of America’s 20-year occupation, the Afghan economy reorganized itself around our aid dollars. Urban areas became acutely dependent on foreign imports for their subsistence. Now that the value of the country’s currency has plummeted, millions of Afghans are struggling to feed themselves.

The deposed Afghan government had built up a $9 billion currency reserve to cushion itself against this sort of crisis. But it kept $7 billion of that sum at the U.S. Federal Reserve. And, as of this writing, the U.S. government has blocked the Taliban — Afghanistan’s de facto government — from accessing their nation’s own assets. Meanwhile, the World Bank, IMF, and the German Agency for International Cooperation have cut funds to Afghanistan. The ostensible aim of these moves is to substitute our lost military leverage over the Taliban for the economic variety: Honor women’s rights, aid American counterterrorism efforts, and allow Afghan dissidents to emigrate — or the development aid gets it.

The problem, of course, is that one cannot shoot this hostage without nullifying Afghans’ most fundamental human right, namely, the right not to be starved to death for their conquerors’ sins. As Tooze writes:

Acute famines generally result from shortages of food triggering a scramble for necessities, speculation and spikes in food prices, which kill the poorest. Those are the elements we can already see at work in Afghanistan.

On August 26 the charity Save the Children reported the following figures for price increases from its staff in cities across the country…As the charity added: “A survey of 630 newly displaced families in Kabul, carried out by Save the Children earlier this month, already found that all of the families had run up debts in order to buy food. Many families have been forced to sell their possessions, cut back on meals or send their children out to work in order to buy food.”

We should not say that we were not warned. These are the signs of a famine to come.

America can exert pressure over the Taliban through measures that do not add to our nation’s crimes against the Afghan people. International legitimacy is a conscionable carrot to withhold, Afghanistan’s reserves and aid dollars are not.

If President Biden wishes to demonstrate that human rights are indeed at the center of his foreign policy, he will cease waging economic war on the people of Afghanistan. If Biden’s critics wish to prove that their opposition to American withdrawal is rooted in concern for the well-being of Afghans — rather than the glory of the U.S. empire — they will swiftly do the same.