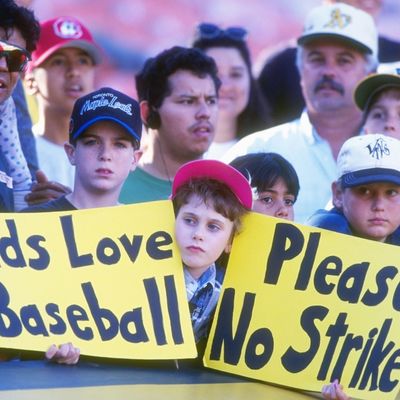

The last time Major League Baseball had a work stoppage, Barack Obama was an associate at the law firm of Miner, Barnhill & Galland, the top-grossing movie in the country starred Jonathan Taylor Thomas and Chevy Chase, and Juan Soto, perhaps the best player in the majors right now, was more than three years away from being born. On March 31, 1995, a then-obscure federal judge named Sonia Sotomayor issued an injunction against MLB owners, who were about to start the season using replacement players. Her ruling led owners and players to come to an agreement the day before the season was set to begin, finally ending the 232-day strike. That episode was so devastating to the sport — it stopped the season dead in August, with no World Series taking place in 1994 — that baseball is still widely seen as the sport with the worst labor-management relations, even though it has in fact gone longer without a stoppage than any other major North American league. MLB has maintained labor peace for longer than a large percentage of current MLB players have been sentient.

When you return from Thanksgiving break next week, that streak is going to end. The current Major League Baseball Collective Bargaining Agreement will expire at 11:59 p.m. on December 1, and, judging from comments by MLB commissioner Rob Manfred last week, owners are set to lock out the players very shortly thereafter. After an undeniably successful season that began with limited fan capacity and ended with tens of thousands of Braves fans screaming (and tomahawk chopping) their heads off as their team won their first World Series in 26 seasons, is about to enter labor Armageddon.

When the lockout actually happens next week — and have no doubt, it’s going to — people who have become accustomed to relative labor peace in North American sports may be shocked. But they shouldn’t be; this has been brewing for a long time. As MLB enters its most precarious period since that awful 1994–95 strike, and as the players and owners prepare to spend weeks and months punching each other in the face, here’s a FAQ on what you need to know.

Why is this a lockout and not a strike?

Manfred was explicit last week: He thinks the best way to avoid losing any regular season games is to force people to the negotiating table immediately. “The pattern has become to control the timing of the labor dispute and try to minimize the prospect of actual disruption of the season,” Manfred told reporters. “That’s what it’s about. It’s avoiding doing damage to the season.” And he’s probably right. Of course, “control” is the key word in his comments, and an important one to remember as negotiations commence. (Assuming they actually commence.) There is still an archaic idea among many fans that sports commissioners are primarily stewards, whose main job is to make sure the game is healthy and strong.

This is maybe, maybe, what commissioners once were, in the vein of Bart Giamatti, the late Yale president (and Paul’s dad), who died shortly after banning Pete Rose from baseball and wrote eloquently about the spirit of baseball. But that’s not what the job is now. In 2021, it’s just about representing the interests of the owners and to be their negotiator. Always, always keep this in mind when the commissioner speaks during the lockout. Because he’s the commissioner, there’s an inherent reflex to believe he is speaking for “baseball.” But he isn’t. He’s speaking for the owners. The Players Association president is Tony Clark, a former Tigers All-Star who played 15 years in the majors. Make sure you give his words over the next month(s) equal weight as Manfred’s, if not more.

What are the issues keeping the two sides apart?

Compensation is the big one of course. Questions about pay undergird everything else. Players want a higher percentage of the revenue than they currently receive, arguing, quite reasonably, that fans are paying to watch them. Every issue under negotiations is ultimately about that revenue split. The sides will be negotiating the particulars of the league’s competitive balance tax — which has begun to work as a salary cap, an extreme no-no for the players. (MLB is the only major North American sports league without a salary cap.) Other major issues up for debate include salary arbitration, the minimum salary, and the tendency for certain teams to “tank” their seasons, slashing payroll in order to build up the farm system and build for the future.

This last issue is a particularly sensitive one because of the way the salary structure is currently set up. The players union has historically focused on securing benefits for its existing members, rather than up-and-comers, so past negotiations have emphasized quality-of-life and salary issues for older players. That has allowed teams to exert cost-control over younger players. Perhaps not coincidentally, teams are now focusing on those young, cheap players at the expense of older veterans, which helps to keep costs down and squeezes out older, more expensive players. The Moneyball revolution, for all its Brad Pitt sexiness, was really about market efficiency. That market efficiency has allowed owners to keep payrolls down by playing younger, cheaper players rather than older, more expensive ones. Players should want to change that. Though it’s up in the air how much they will fight for it.

That doesn’t sound too impossible to solve.

You’d think, right? The problem — and this is another reason to remember that Manfred’s job, like Roger Goodell’s in the NFL, is to represent the owners — is that no one knows exactly how much revenue MLB brings in. The league gives out numbers specifically focused on “baseball-related revenues.” But this is an increasingly sketchy metric. Case in point: Many teams now see their stadiums as real-estate investments, and focus on building the area around the ballpark and profit off that, using the team as a cudgel for outside investment. The Ricketts family has done this with Wrigley Field in Chicago, and their model has been followed by many teams, from the Cardinals and their Ballpark Village in St. Louis to the World Champion Braves, who seem to have built a stadium in suburban Cobb County solely for the real-estate play of the new “Battery” project. (Using tax dollars to do it, of course.) Because MLB teams aren’t publicly held companies, they don’t have to disclose how much money they bring in. Do those real-estate plays count as “baseball-related revenue,” and if so, how much? One thing is clear: While the owners plead poor (they especially did so during the pandemic), they inevitably make a huge amount of money whenever they sell a team — a pretty good sign that the business isn’t struggling all that badly. Players want a larger piece of the pie. But they can’t even find out how big the pie actually is.

Add to this decades of owners being less than forthcoming with players about just about every financial issue, and you can understand why players don’t always believe they’re working with good-faith negotiators here. The two sides don’t trust each other, which makes it difficult to even get them talking about the most important matters.

So the players are going to fight like hell this time, right?

We’ll see! One of the major issues for the union is the lack of unity displayed by players in past negotiations. Some want to change the sport’s entire financial structure; some just want raises for themselves; some don’t want to strike at all. Players would seem to have a case to shake up the current system after taking it on the chin the last few go-rounds with owners. And the fact that more and more teams are slashing payrolls and putting uncompetitive teams on the field, knowing they’ll make a profit whether they win or not, is an existential problem for the game itself. But it’s one thing to know these things, and another to wave good-bye to a steady check (during a career that, on average, only lasts a few years) to make sure future generations have it better than you. Some observers also believe the union is perhaps not best served by having former players at the helm — players who inherently have a bias toward quality-of-life issues rather than wholesale structural change.

Still, the pandemic may have shifted things. There were massive disagreements between owners and players about how to run the 2020 COVID-19 season, and it got so ugly that it almost didn’t happen. That experience galvanized many players, and they may dig in this time in a way they haven’t in the past. We will see.

Whom should I side with?

As a general rule, it’s better to side with players in labor disputes. They are, after all, the ones with the tougher job, and the ones we are all paying to see. There is still a strange contingent of fans that thinks it’s harder to be an owner (a position that is often inherited and one that generates consistent profits without many outside challenges at all) than it is to be a player (a job where everyone screams at you while a ball comes at you at 100 mph, and if you are not the absolute best in the world at what you do, there is an endless queue of people waiting to take your place), and thus side with owners in these disputes. But this is a fallacy of visibility. Players strike out when fans want them to hit a home run, and so, because their salaries are a matter of public record (unlike owners), it can feel like they are “overpaid.” Owners have it much easier: They don’t have to withstand much scrutiny, and they have essentially lifetime job security. And they probably screw up even more often than the players — we just don’t witness it on a daily basis. You might not be able to run 90 feet without passing out. But you’re a lot more like athletes, in a labor sense, than you are like an owner.

But. But! If you are a baseball fan who may philosophically side with the players but really just want there to be baseball this season, it’s possible you don’t want players to be hard-liners. After all, one of the major reasons labor peace has presided for so long is that players have been focusing on surface matters like roster spots and paid time off and less on the big economic issues. If players are as truly unified as they claim, that’s great for them and maybe even for the financial fundamentals of the game in the long term. (And maybe an overall moral good as well.) But it also means this lockout could drag out a long, long time, and maybe even cost games. There are some signs that fans are more amenable to a pro-player mind-set than they might have been in the past. But will that last if a lockout drags into spring training, or even postpones Opening Day? This is not an academic question. The public relations war of the next few weeks and months will be a major factor in who comes out on top. Players will need public support. Will they have it?

They’re not going to try the replacement players this time, are they?

No. First off, it’s a lockout, rather than a strike; owners would have no standing to replace players that they’ve frozen out from taking the field anyway. In an era of player empowerment and more outgoing athlete personalities, it’s difficult to imagine replacement players ever catching on in American sports again. It’s sort of wild it was ever considered in the first place.

When do I need to start worrying about this?

Well, free agency is going to freeze when the lockout happens, so if you’re enjoying the Hot Stove, that’s about to end. (I personally would like to know who the Yankees’ shortstop is going to be next year.) But if there isn’t a resolution by, say, Groundhog Day, it’s time to be very concerned. If they can get an agreement hammered out by the end of the calendar year, there should be minimal disruption. But neither side is talking as if they expect that to happen.

Great.

Look, baseball fans of a certain age are more than used to this. Labor issues have been a staple of the sport for decades: The last 26 years are the aberration, not the norm. (Ask White Sox and old Expos fans about the cruelty of canceling the 1994 World Series.) As for updates, I’d recommend checking in every once in a while but not obsessing over every negotiation posture or bomb tossed via the press. Despite the perpetual claims that baseball is somehow in some sort of cultural peril, the sport is doing well. There is still a lot of money in it — so much that a fight like this is worth having. Don’t pull your hair out about this just yet. There will be plenty of time to worry in 2022, if the work stoppage makes it that far. One thing is clear, though: The era of labor peace in baseball is about to be over. What the next era looks like will be decided in the next few weeks … and hopefully not the next few months. Labor Fight Fever: Catch it!