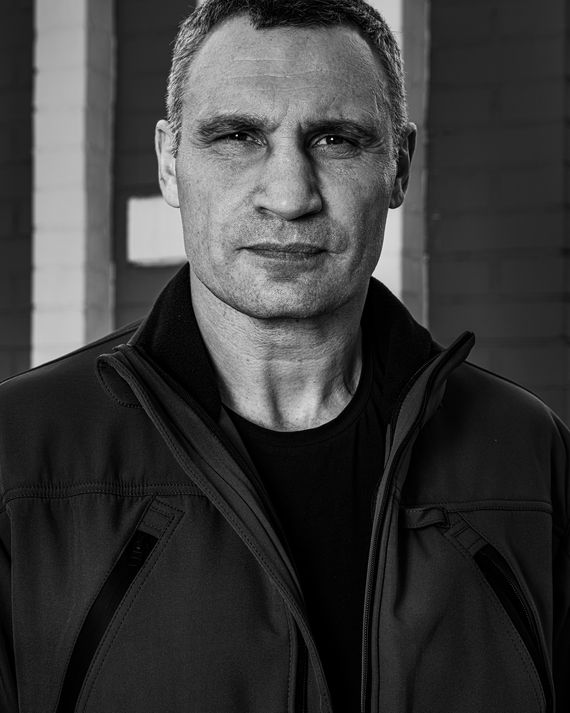

Vitali Klitschko is speaking from an office in Kyiv when he plays a recording he made of an air-raid siren, which begins broad and low before climbing into a high-pitched scream. “Two, three, four times during the night we hear the siren and we immediately have to go to the bunker,” Klitschko says through Skype, dressed more like a soldier than a mayor in a camo-green insulated coat zipped to his chin. Perhaps a little tired, he rubs the bridge of his nose, which looks flattened from his time as the world’s former heavyweight-boxing champion.

Inside the bunker, Klitschko recalls, after the sirens go quiet, the phones start ringing with reports about Russia’s latest war crime in Ukraine. That’s when he leaves and rushes to the smoldering buildings, where he says he helps firefighters with rescue efforts. “A few days ago I was visiting an apartment building that was destroyed from a rocket,” he says. “An old man comes to me and tells me, ‘Mr. Klitschko, Mr. Mayor, I’m homeless now. What do I have to do?’ I gave him a proposal to bring him to safety in western Ukraine. His answer shocked me. He told me, ‘I’m sorry. I don’t want to leave the city, because I spent my whole life here. I want to ask you, mayor, give me weapons, please. I want to defend my city.’”

Some of the residents have been surprised to see Klitschko, who’s been in office since 2014, but he says this is the job of a mayor at war. Before the invasion, he was preparing this year’s budget to fund infrastructure projects and a tourism zone. The summer was supposed to see Kyiv host the World Minifootball Federation’s world championship. “Now we have a totally different priority,” he says, “to save the lives of the people.”

Klitschko is speaking on the one-month anniversary of the Russian invasion, which sought to quickly decapitate Ukraine’s government by seizing his city. “The Russians had plans to be in Kyiv four days after the beginning of the war,” he says. Instead, they were blunted by ferocious resistance. “The Russian soldier is fighting in Ukraine for money. The Ukrainian soldier is fighting to defend our homeland. Weapons are important, but the spirit of warriors is more important.” One of them is his younger brother, Wladimir, who is patrolling the streets as a member of Kyiv’s civil defense force. Sometimes they give interviews together, an echo of when the Klitschkos dominated the boxing world in the 1990s and early 2000s. That’s the extent of the family’s involvement in the war: Vitali says he sent his wife, children, and mother out of the country before the invasion, though they talk almost daily.

Once larger in population than Rome or Paris, Ukraine’s capital has seen half of its 3 million residents leave since the war began. Since then, the Russian army has tried to encircle Kyiv, but on the day we speak, Ukrainian forces had succeeded in pushing them back, giving the city some respite from shelling. Today, Klitschko tells me, was the first day since the invasion that the city had gotten through the night without any bombings. “I am very happy right now,” he says.

Other cities are not as fortunate. Right before our call, Klitschko was speaking to the mayor of Chernihiv, a city 100 miles northeast of Kyiv being raked with Russian shells. “I was listening to explosions,” he says of their phone call. Chernihiv’s mayor asked him for generators after Russia destroyed the city’s electrical grid, a harbinger of what might happen next to Kyiv. Due to its slow advance across the country, Russia’s army is laying siege to the towns it cannot capture. “I can see in other cities the genocide of Ukrainians,” he says. “I can expect what happens in Chernihiv, Kharkiv, Mariupol to happen also in my hometown.”

Of course, Vladimir Putin’s government claims only legitimate military sites are targeted — which sets Klitschko off. “They are liars because they say they are fighting Ukrainian soldiers, but it is not true. They destroyed the cities, the apartment buildings, civilians, women, children. We guess thousands of civilians have already died in this senseless war,” including, he says, people he knows.

As he speaks, NATO leaders including President Joe Biden are gathering in Brussels to discuss how else to help Ukraine. Western politicians have been quick to praise the bravery of Klitschko and Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, but at the same time they refuse to listen to both men’s demands for sophisticated anti-aircraft systems and fighter jets to stop the Russian air force from obliterating cities. And Europe still buys natural gas from Russia. “My message to politicians who from one side support Ukraine, from another side don’t want to break relationship with those Russians? You can’t be half-pregnant,” Klitschko says. “Right now, the world is white-and-black. Many politicians try to make a business with Russians: Every dollar, every euro, every cent, they invest in the Russian army that’s destroyed Ukraine.”

Still, Klitschko says, “I can’t hate Russians.” I ask him how, after all they’ve done. “My mother’s Russian. I can’t hate my mom. Half of my body is Russian blood. My first language is Russian. And a lot of people here in Ukraine are Russians, fighting for Ukraine.” Even so, there’s no confusion about his loyalty. When he was young, Klitschko served in Ukraine’s military, and his father was a Ukrainian general in the Soviet Union’s military who taught him the “biggest privilege” is to “die for your country.”

Klitschko is reluctant to guess what the second month of war would bring to Kyiv, but he lets himself make one prediction: Russian soldiers will never take the city. “I tell you not as an official, but as a citizen: Better that we die than we give up.”

More on ukraine

- House Passes Ukraine, Israel Aid: How It Happened

- Trump’s Plan for Every Foreign-Policy Problem Is Himself

- Putin Is Winning — and He’s Flaunting It