The “work from home” revolution has been very good for political columnists who like to write shirtless in pajama pants and share too much personal information with their readers. But the phenomenon hasn’t been so great for America’s cities.

The nation’s office buildings aren’t as empty as they were before COVID vaccines became widely available in spring 2021. But they’re still far less populated than they were in 2019. A recent analysis of Census Bureau data from the financial site Lending Tree found that 29 percent of Americans were working from home in October 2022. In New York City, financial firms reported that only 56 percent of their employees were in the office on a typical day in September.

Full-time remote work has grown less prevalent since the worst days of the pandemic. But flexible work arrangements — in which employees report to the office a couple times a week — are proving stickier. A recent paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research estimated that 30 percent of all full-time workdays would be performed remotely by the end of 2022.

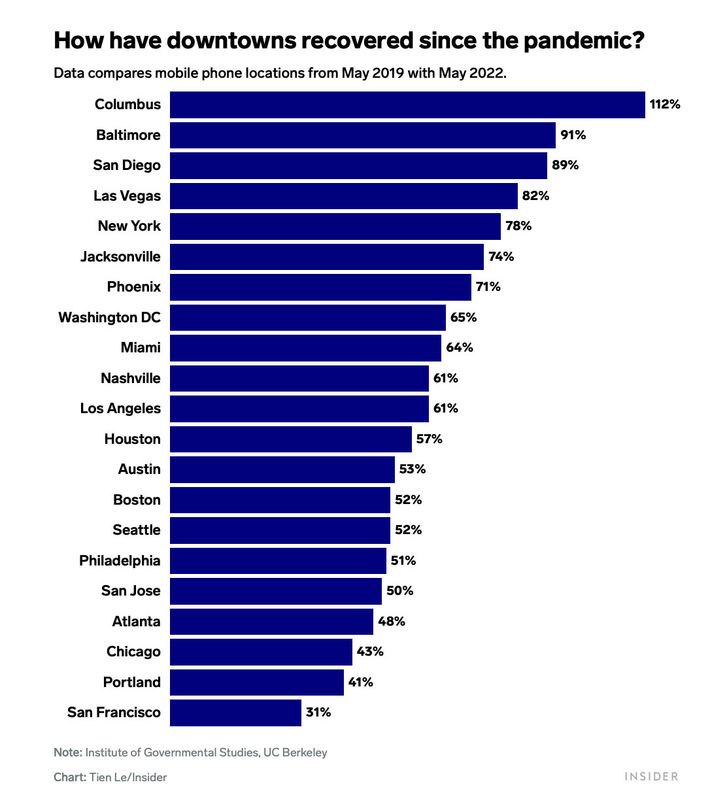

As Insider’s Emil Skandul illustrates in an excellent piece, these surveys and projections are buttressed by mobile phone data showing that, in virtually all major U.S. cities, foot traffic in central business districts is down substantially from 2019.

And collapsing office attendance rates are taking cities’ tax revenues down with them.

When only 50 percent of a company’s staff leave their homes in the morning, that firm’s desire for floorspace plummets. If storm-clouds appear on the economic horizon — like, say, a central bank dead set on slowing the economy to kill inflation — downsizing your office becomes the easiest way to cut expenses. Thus, as rising rates have laid tech low, San Francisco’s signature office towers have emptied out. In New York, meanwhile, Meta has ditched 450,000 square feet of office space. Across the nation as a whole, only about 47 percent of offices are occupied.

All this translates into plummeting demand for commercial real-estate, which translates into plummeting property values, which translates into plummeting tax receipts. A recent study from New York University’s Stern School of Business found that office values fell 45 percent in 2020, and are likely to remain 39 percent below pre-pandemic levels for the foreseeable future. If that projection proves true, it would wipe $453 billion in property values off American cities, thereby slashing a critical source of municipal revenues.

In New York City, property taxes are the single largest source of public funds, supplying one-third of the city’s tax revenue. Office buildings account for one-fifth of that sum. The declining market value of Manhattan’s major office districts alone cost the city $5.24 billion in revenue.

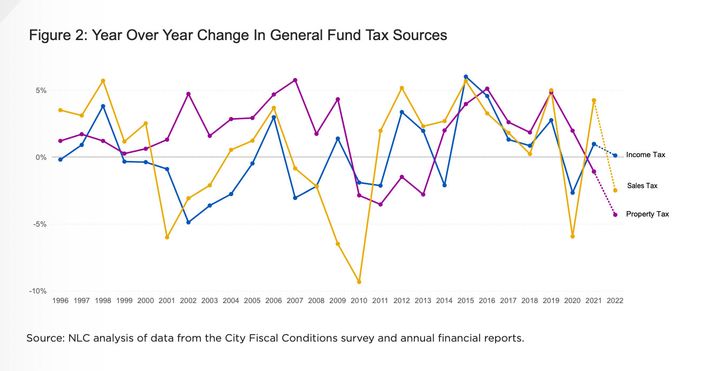

Remote work’s toll on cities does not end with its implications for property tax revenue. Enable suburban commuters to work from their dens several days a week, and you transfer all manner of smalltime commerce — lunch orders, after-work drinks, etc. — from the urban core to its periphery. And lost transactions mean lost sales taxes. U.S. cities expect their sales tax revenues to decline by an average of 2.5 percent in 2022, according to a survey from the National League of Cities. Last year, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer estimated that remote work would cost the city $111 million in sales tax receipts annually.

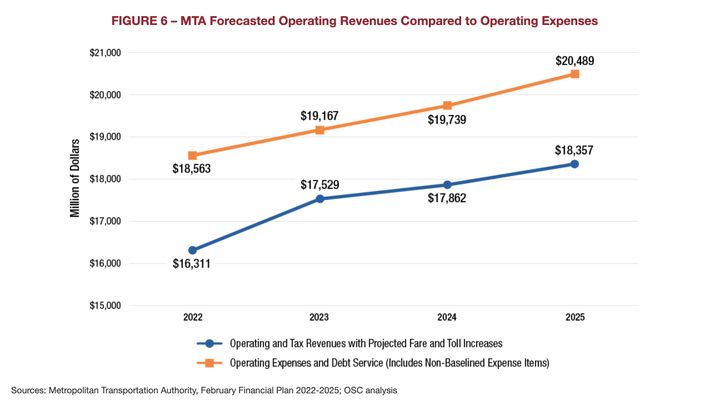

Meanwhile, emptier office towers also mean emptier subways and buses. Although mass transit ridership has recovered from its COVID-era lows, it’s plateaued at roughly 70 percent of pre-pandemic levels. That poses an existential threat to municipal transit systems, many of which were struggling to operate on budget even before the COVID crisis. In New York, the Metropolitan Transit Authority is poised to see a widening gap between its revenues and operating expenses as this decade progresses.

The great danger for cities is that these trends could become self-reinforcing. Falling revenues could translate into lower-quality public services (e.g. less reliable subways, less well-maintained infrastructure, lower performing public schools, stingier safety nets), which render cities less attractive to high earners, who then decamp for the suburbs in greater numbers, thereby depressing revenues further. Meanwhile, underpopulated downtowns are less conducive to successful small businesses and more conducive to crime. As central business districts become home to fewer restaurants and more criminal activity, more firms will flee them, leading to even more underpopulated office towers.

For now, the American Rescue Plan’s copious aid to states and municipalities are keeping cities out of this vicious cycle. But those funds will dwindle in the coming years. In the National League of Cities recent survey, nearly one-third of cities said that they will confront financial challenges next year, as relief funds grow thin.

It is possible that work from home will simply fall out of fashion as the pandemic recedes into history. But given the myriad advantages that flexible work arrangements have for both employees and firms, cities shouldn’t count on it. Instead, major U.S. cities should capitalize on the one benefit of commercial real-estate’s collapse: The newfound potential to create a ton of new housing in already constructed, centrally located buildings.

America’s most successful cities have long failed to expand their stocks of housing in line with demand. The result has been a perennial crisis of affordability that constrains urban growth, transfers vast sums of money from workers to landlords, and displaces longtime residents. Restrictive zoning codes — and community opposition to new construction that threatens to bring more noise, traffic, and competition for parking spots — have helped entrench this sorry state of affairs.

But vacated office towers typically reside in districts already zoned for both residential and commercial activities. And since the buildings are already built, they tend to attract less community opposition. Their centrality, meanwhile, makes them potentially attractive residences for urbanites who wish to walk to work, and/or have virtually every good or service one could ever want within a hop, skip, and a jump.

Alas, converting office buildings into housing is easier said than done. Commercial buildings tend to have far fewer bathrooms and kitchens than residential ones require. Which means that any conversion demands reconstructing a tower’s plumbing and electrical systems. Expenses add up quickly, especially at a time of elevated construction costs.

Meanwhile, many office buildings do not meet all of the standards that municipal zoning codes require of residential buildings. Offices tend to have much more interior space between windows, leaving much of their floor plans without external light. Additionally, in New York City, residential buildings are generally required to have 30-foot rear yards, in order to ensure a modicum of light and air. Commercial buildings often have smaller rear yards, while also running afoul of the parking minimums that many cities impose on residential towers.

Faced with the high costs and regulatory headaches of attempting a conversion, many real-estate developers have resigned themselves to lower revenues from their commercial properties, while nursing hopes that remote work will prove to be a mere fad.

If conversions don’t pencil out for private developers, however, they promise profound benefits for cities as a whole. Turning thinly populated office towers into apartment buildings would ease cities’ housing shortages, while boosting both downtown commerce and property values and, therefore, tax revenues.

Thus, city and state policymakers would be wise to help lower both the funding and regulatory hurdles to mass office-to-residential conversions.

Cities have often sought to promote development by giving tax credits and abatements to new projects. Yet one of the main objectives of promoting office-to-residential conversions is to increase property tax receipts. So, trying to spur such developments by doling out property tax breaks seems less than ideal.

Instead, cities should help finance new projects with revolving funds that secure the public sector a cut of the ultimate proceeds. Montgomery County’s Housing Production Fund in Maryland offers one model for this form of public-private development. In simple terms, the county’s fund encourages private investment in housing by providing partial funding for new projects, thereby reducing the financial risk that developers must assume when pursuing new construction. In exchange, developers agree to place income restrictions on 30 percent of the units in a given building, and to share a portion of their ultimate profits with the government. Through this mechanism, Montgomery County has managed to catalyze the construction of new affordable housing, at a negligible net-cost to the public sector.

While providing capital for office-to-residential conversions, cities should also exempt such projects from their most burdensome zoning requirements. Residential towers in central business districts replete with transit options should not have to comply with parking minimums. And they probably don’t all need 30-feet yards either. Relaxing such standards will necessarily mean that some new housing developments will offer residences with unusually poor light and limited windows. But they will also offer renters and buyers the myriad amenities of a city center and benefits of new construction. Having poorly-lit new housing is not ideal. But having an acute shortage of affordable housing — and a superabundance of downtown office space — is even worse. New York, Los Angeles, and myriad other cities have offered regulatory exemptions to conversion projects in the past, and have rarely regretted trading stringent standards for more housing units.

Indeed, the benefits of office-to-residential conversions are so significant, cities should consider exempting them even from the requirement that all legal bedrooms have windows.

Given the massive core-to-window depths of contemporary office buildings, converting many such towers to residences will require tolerating some deeply weird floor plans. The real estate developer Bobby Fijan recently tweeted this example of how a typical modern office could be refashioned into a spacious yet bizarre home:

Not everyone is going to want to live in a 2,500 square-foot apartment with a massive common area and 4 windowless bedrooms. But as Matt Yglesias argues, some people probably would. Personally, I’m a very light sleeper who is routinely awakened by city noise and morning light. So the idea of having a bedroom insulated from both by solid walls has some appeal. If cities are faced with a choice between letting office towers sit vacant, or letting photophobic bargain hunters live in windowless bedrooms, they should opt for the latter.

The liberation of America’s white-collar homebodies need not come at cities’ expense. The remote work revolution could devastate municipalities’ downtowns and finances, or it could help resolve their housing crises. If they can summon the requisite policy imagination and flexibility, city officials can make “work from home” work for everyone.