This morning at 8 a.m., New York Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger and CEO Meredith Kopit Levien received a letter from Bill Baker, unit chair of the Times guild, that was signed by more than 1,000 employees. Subject line: “Enough. If there is no contract by Dec. 8, we are walking out.”

Back in September, I wrote about how the unionized staff and management hadn’t come to terms on a new labor contract and were threatening to do something like, well, what this letter has finally threatened to do. For months, the newsroom has been pressing its publisher for a bigger share of the Times’ profits, but it turns out the guy whose predecessors were nicknamed Punch and Pinch is no pushover. So now they’ve decided to give the boss a hard deadline. The letter demands a weeklong marathon bargaining session over health-care funds and return-to-office policies and their pension plan. But what the employees really want is permanent increases in base pay. If they don’t get enough of a salary bump, they’re going to stop working for 24 hours next Thursday.

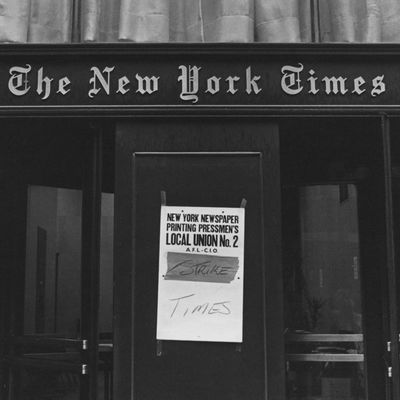

A walkout is technically a strike, though one with an end date. There was a one-hour walkout over a lapsed contract in 2011, and another quick afternoon walkout in 2017 over copy editors being eliminated. But those were mostly shows of solidarity. What the employees are preparing to do next week would be something not seen at the paper of record since 1978. Picture it: a full day without the New York Times. No one covering the tumult in Guangzhou or inside Buckingham Palace or what our president is saying. From midnight to midnight, no reporting, no filing stories, no podcasting, no comment moderating, and definitely no responding to editors’ queries. There would be no live briefings. (You’d be shocked at how many people it takes to produce one of those things.) Even logging into Oak (that’s their CMS) will be seen as scabby. Reporters tell me they’re ready to picket outside the building, too. (“There will be plenty of photo-ops,” muses one.) Sure, masthead myrmidons will have enough copy in the hopper to keep that homepage humming for a little while, and it’s not as though the app on your phone will suddenly go blank. But the walkout threat is a marked escalation from an ordinarily fissiparous newsroom. It’s the sort of stunt that precedes an actual sustained strike.

“Obviously the next step, if we can’t get anywhere at the negotiating table, is to consider things like a strike authorization vote,” says reporter Michael Powell, adding that “none of us want to step into the terra incognita if this isn’t seen as a significant warning shot.” Senior staff editor Tom Coffey has been at the Times since 1997 and says, “I think this is the worst I’ve seen it since the staff mutiny that led to Howell Raines being fired.”

The staff is steamed because they feel the paper is sitting on a pot of gold. “We have been lectured about the dire economic future the company faces — even as the company tells Wall Street about a successful corporation that can afford to pay millions in salaries and benefits to its top executives,” states the letter. (According to an SEC proxy statement, Sulzberger’s total compensation grew nearly 50 percent last year to $3.6 million up from $2.4 million; Kopit Levien’s total compensation was $5.8 million, up from $4 million.) Powell says “management’s tactics feel increasingly provocative” and that “there’s a real sense of building anger around this. I had to bring my computer in to get it worked on the other day and the guys up in the computer shop and I were yammering about this, and I talked to the security guards about it, too. It’s a really bad place for a paper that, relatively speaking in this day and age for a newspaper, is doing quite well and has a pretty well-defined future.”

But the word relatively is key. This winter is shaping up to be a frosty one for everyone in the media as the economy teeters on the edge of a recession. On Monday, Bob Iger said he isn’t lifting Disney’s hiring freeze. On Tuesday, James Dolan sent a memo to his employees at AMC Networks about a coming “large-scale layoff.” On Wednesday, Chris Licht cut the cord on more CNN employees, and there were layoffs at CBS Studios, too. That same day, Sally Buzbee killed the Washington Post’s Sunday magazine, citing “economic headwinds.” On Thursday, there were cuts at Gannett. Penguin Random House is expected to have layoffs in January, and the HarperCollins strike is getting ugly.

“If I were a paranoid person,” says Times television critic James Poniewozik, “I might even say that the company was slow-walking the negotiations in the hopes that they might strike a deal on wages at what seems to be a more dire economic time. Fortunately or unfortunately, the Times is doing pretty well. I’ve been a journalist for a long time. It’s kind of always bad times for the media, and yet the Times, to its credit, is one of the few success stories in print and non-print media, and that’s because of us.”

Film critic Manohla Dargis says, “The paper represents and advocates on behalf of so many good and noble values, but I think the paper sometimes forgets that we are not here as priests and nuns having committed ourselves to Christ for no money. We are laborers and we need to get paid for the work, and I think if you’re going to advocate for good, you have to actually be good as well.”

Labor unrest at the Times is always awkward for the top editor, who gets pinioned between the newsroom they run and the business side to which they must answer. The big walkout would be the first real crisis for new executive editor Joe Kahn. Staffers report that he has been typically inscrutable through it all. Is he blameless? “Anyone on the masthead level, I’ve got to assume they’ve got the management’s ear to some extent,” says Poniewozik, “and if they want peace in the newsroom, like we all do, I would hope they’re using their voices however they can to lean on the ownership of the paper and tell them that this is a real problem.”

A Times spokesperson responded, “While we are disappointed that the NewsGuild is threatening to strike, we are prepared to ensure The Times continues to serve our readers without disruption. We remain committed to working with the NYT NewsGuild to reach a contract that we can all be proud of.”

“The paper,” Poniewozik says, “doesn’t write itself.” It might have to try, at least for a day.