This week’s dueling AI search presentations from Microsoft and Google marked the resumption of hostilities in the long-dormant search wars. Microsoft, which is a major investor in OpenAI, announced it would be incorporating ChatGPT-style features into Bing, its also-ran search engine. Google unveiled a ChatGPT competitor called Bard and previewed how related technologies would be incorporated into Google Search.

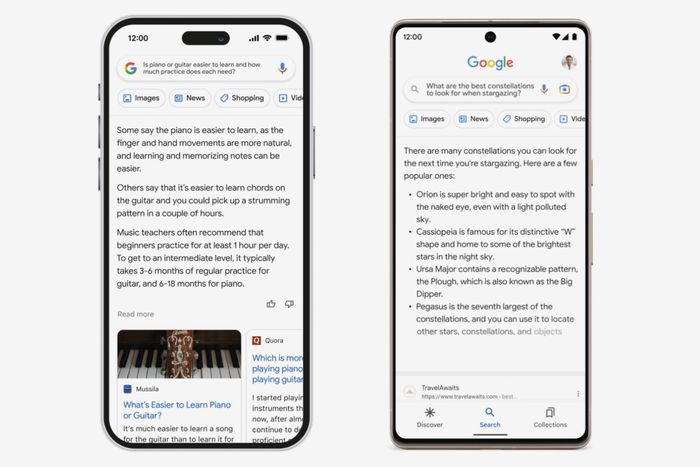

“Soon, you’ll see AI-powered features in Search that distill complex information and multiple perspectives into easy-to-digest formats, so you can quickly understand the big picture and learn more from the web,” wrote Google CEO Sundar Pichai. In addition to a ChatGPT-style conversational experience, the new Bing, according to Microsoft, will review “results from across the web to find and summarize the answer you’re looking for.”

Each company talked about the arrival of a new era, spoke about the years of incredible research that made these new features possible, and shared some demos. Microsoft, which is opening up the new Bing for testing, is already garnering rave reviews. Google, which has been slower to release its new LLM-powered tools to the public, saw its stock take a nosedive after sharing a demo in which Bard, asked to describe some “new discoveries from the James Webb Space Telescope,” confidently made one up out of thin air.

In one sense, what audiences saw was certainly new: a pair of search engines engaging with queries in plain, colloquial language, interpreting questions and summarizing answers with aptitude. What they saw was also darkly funny beyond Google’s error: Two of the tech industry’s biggest and most dominant firms were announcing, with great fanfare and excitement, the imminent arrival of search engines that can, by leveraging cutting-edge proprietary large language models, provide basic, relevant results somewhere near the top of a search page. They were offering a preview of the future of human-computer interaction by delivering on the promise of … Ask Jeeves.

A great deal of what made these demos appealing, from a searcher’s perspective, had little to do with the underlying technology at all. What we saw were glimpses of a Google experience with fewer misleading ads, less scrolling, and fewer clicks. One of the nicest things about these search-engine demos of the future was how much they resembled, on the surface, the search engines of the relatively recent past, before their parent companies made them worse to use. They’re clean. They engage with queries in a way that makes intuitive sense, rather than through the odd, scrambled input-output metaphor of Google and Bing, circa 2023. Before: You searched, they found. Now: You type in a term or some words or a question or whatever and they, uhh, provide results. Soon, according to these demos: You’ll ask, they’ll answer.

The new Google and Bing appear, in their early demo forms, to be gloriously free to simply do what is asked of them, without the various other accumulated considerations that have led to search pages feeling like such a frustrating, cluttered mess. They were as much a reminder of how terrible the search experience has become as they were a case for search-via-conversation, powered by AI.

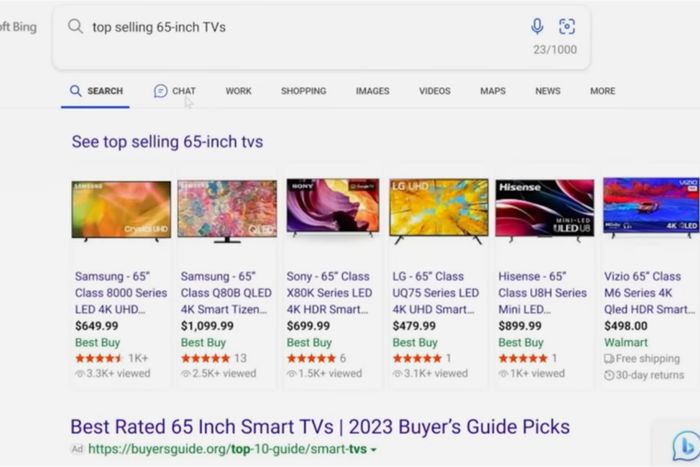

Both companies showed off conventional search pages supplemented with summarized results as well as chat-style “conversational” interfaces. Microsoft’s Bing demonstration highlighted the difference between old and new interfaces. In an example search, “top selling 65-inch TVs” produced a page like this:

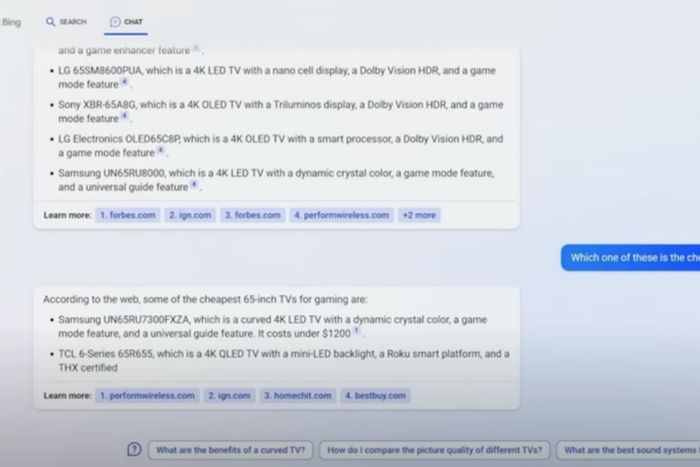

By switching to chat mode, Bing produced this:

Very different things are going on, here, under the hood, and I don’t mean to suggest the underlying technology here is insignificant or irrelevant. But the contrast is fascinating for reasons that have nothing to do with machine learning. The conventional search-engine interface is terrible on its own terms — the first thing users see, even in this technology demo, is a row of purchase links and an advertising pseudo-result leading to a website I’ve never heard of. The “search,” such as it is, is immediately and constantly interrupted by the company helping you conduct it.

The chat results are, by contrast, approximately what the user asked for: a list with no ads and a bunch of links, and a summary of the sorts of articles that current Bing users would have encountered eventually, after scrolling past and fending off the various obstacles and distractions and misdirections that are typical of modern search, as designed by Google and Microsoft. Microsoft is showing off its OpenAI integration, here, but it’s also just choosing a different way to display information — one that it could have used for years.

In the narrow context of the search wars, this state of affairs probably favors Microsoft. Bing just doesn’t matter that much to its parent company, which makes most of its money selling access to software, so a newer version with fewer ads could be worthwhile if it can steal away market share from a much larger competitor. By contrast, Google, which is primarily an advertising company, risks blowing up its core business model by going down the path suggested by its demos. “From now on, the [gross margin] of search is going to drop forever,” Nadella told the Financial Times. “There is such margin in search, which for us is incremental. For Google it’s not, they have to defend it all.”

There are much bigger considerations than the fortunes of Microsoft and Google, of course. Search engines still provide the de facto gateway to the broader web, and have a deeply codependent relationship with the people and companies whose content they crawl, index, and rank; a Google that instantly but sometimes unreliably summarizes the websites to which it used to send people would destroy that relationship, and probably a lot of websites, including the ones on which its models were trained, and which they would need to continue to ingest to synthesize, say, the news. This is, like most AI stories, a story about automation — in this case, of the creation of relevant search content, a task previously undertaken, by, well, the entire web, over which Google, by virtue of its size, has gradually taken worrying amounts of control.

These are demos, though, and it’s unclear what will really make it out to the general search-dependent, ad-impression-producing public, or how it will evolve or fail once it encounters the countless and often vital demands of real users. Dazzling new features powered by novel technology don’t guarantee mass adoption, and lots of companies have lost lots of money assuming that people must want to have human-style conversations with their computers. Likewise, a tech company’s ability to make a more satisfying or appealing product doesn’t guarantee that it will actually deliver one, especially if that product might interfere with its main source of revenue. What Microsoft and Google did make abundantly clear, however, is that they know search is broken — of course they do, because they broke it.