Nearly three weeks ago, the FDIC and Federal Reserve took extraordinary measures to contain the fallout from the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. Those efforts saved SVB’s depositors from the threat of bankruptcy and averted a domino rally of catastrophic bank runs. Nevertheless, the SVB crisis is still weighing on America’s small and regional banks, increasing the risk of a near-term recession in the process.

The fundamental problem facing such banks is simple: When the Federal Reserve raises interest rates, the return on cash stored in a money-market savings account goes up. Banks can respond to this reality by raising the interest rate on their savings accounts to a level that’s competitive with the money markets. But that would drastically increase their funding costs. And since ordinary depositors don’t usually pay all that close attention to whether their bank is paying a competitive rate, banks typically feel little pressure to do so.

But SVB’s collapse changed that. Even though the government bailed out the bank’s depositors (and those with less than $250,000 in their accounts were never at any risk of losing money), days of national news coverage focused on the prospect of firms being wiped out for storing their cash with a bank that was theoretically “small enough to fail” led many Americans to reconsider their own banking practices. At the same time, as spooked investors sold off the stocks of regional banks, depositors at those institutions started fretting for their money’s safety.

This nationwide bout of financial self-reflection led many households to realize that they could secure a higher return on their savings — at roughly the same risk — by transferring their bank deposits into a money-market savings account. Meanwhile, the most paranoid depositors at small and regional banks decided to shift their savings onto the books of Wall Street megabanks that face a smaller risk of failure, and a higher likelihood of getting bailed out in the event of a calamity.

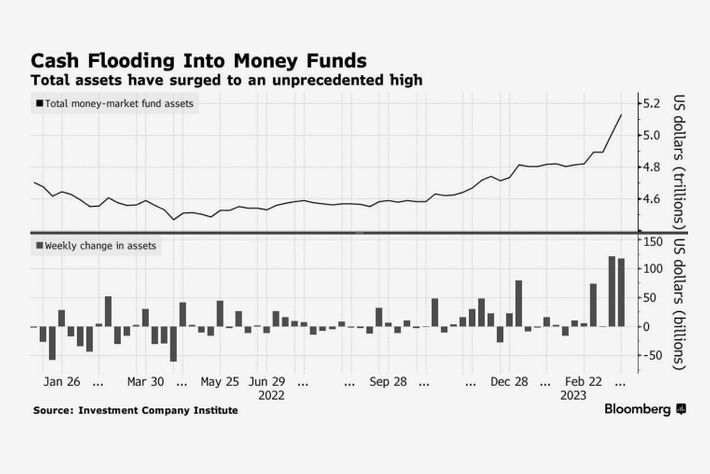

As a result, in the wake of SVB’s collapse, America’s 25 largest banks gained $120 billion in deposits, while smaller lenders bled $108 billion from their accounts. Assets held in money-market funds, meanwhile, hit a record $5.2 trillion this month, as savers added more than $300 billion to them in the last three weeks.

This has adverse implications for American economic growth, since savings stashed in money markets do less to fuel investment and consumption than those stored at banks. At present, close to $2.3 trillion of all money-market funds are parked at the Federal Reserve’s reverse repo facility, where they are effectively removed from circulation. Barring a change in Fed policy, more money is likely to flow into that lucrative spot on the economy’s sidelines, as the reverse repo facility offers a virtually risk-free 4.8 percent annual return on cash.

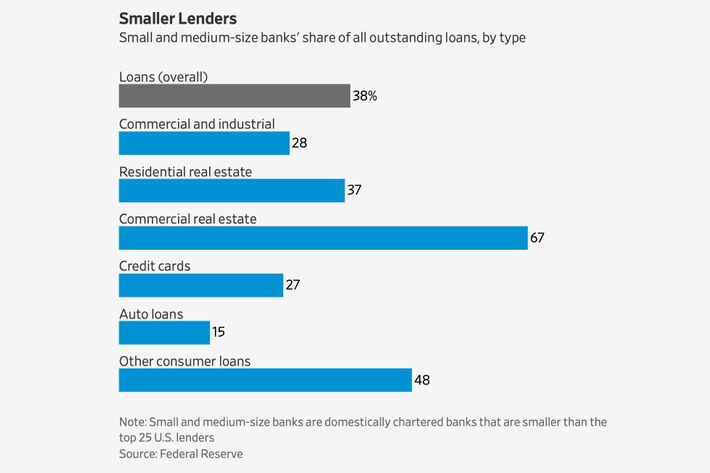

This leaves small and regional banks with less scope for providing capital to borrowers. With less cash on their balance sheet, and depositors already on edge, such lenders are bound to grow more risk averse and tighten credit standards. Which has major implications for the broader economy. Smaller banks have expanded lending by more than Wall Street’s titans since 2000, supplying 38 percent of all outstanding loans.

What’s more, midsize banks are especially crucial players in the commercial real-estate industry, providing 67 percent of all loans to that sector. That’s less than ideal for both builders of office towers and smaller banks, since the former were already facing serious economic headwinds, even before their primary lenders started tightening access to credit.

As of late January, occupancy rates at U.S. offices remained at roughly 50 percent of their pre-pandemic levels. Those vacancies were already starting to weigh on employment in the commercial real-estate sector, even before the bank run at SVB. As Preston Mui and Alex Williams of the think tank Employ America note, hiring in the building services industry — which is to say, for roles such as “janitors, landscapers, security guards, office clerks, and freight workers” — has been stagnant for months.

As commercial real-estate firms see their costs of credit rise, stagnant hiring in the sector might give way to net job losses.

For their part, many midsize banks were already nervous about their exposure to commercial real-estate before this month. Last year, a report from Moody’s Investors Service found that 27 regional banks has high concentrations of commercial real-estate loans on their balance sheets, holdings that could prove problematic in the event of a recession.

The combination of commercial real-estate builders and managers reeling from remote work and more costly credit — and banks nervous about their exposure to the industry — threaten to reinforce each other in a vicious loop: As banks raise credit costs or pull back support, commercial real-estate firms could grow financially weaker, prompting banks to further withdraw support.

Beyond the peculiar risks to commercial real-estate, risk-averse small and midsize banks are liable to make credit more difficult and expensive to secure throughout the economy, leading businesses to forgo planned investments, and consumers to cut back on debt-financed spending.

On one level, a pullback in borrowing-fueled consumption and investment is precisely what the Federal Reserve has been trying to engineer. The central bank’s interest rate hikes have been aimed at slowing spending throughout the economy, so as to bring down inflation. But there is a substantial difference, at least in theory, between gradually reducing access to credit through predictable increases in benchmark interest rates and a sudden collapse in credit availability.

“If it’s suddenly much harder to get an auto loan, a consumer loan, a mortgage for commercial real estate simply because smaller regional banks have to reorganize balance sheets,” Torsten Slok, chief economist at the private equity firm Apollo Global Management, recently told the Wall Street Journal, “then you run the risk that many people won’t get the financing to buy that car, to buy that washer, and that corporate lending takes a hit.” Before the SVB crash, Slok had expected the U.S. economy to avoid recession this year. Now he believes it is headed for a “painful downturn.”

If a near-term recession has become more likely, however, it remains far from assured. The U.S. labor market remains nearly as strong as it has been in decades, with employers adding 311,000 jobs in February. As employment increases, so do overall incomes and spending levels. In February personal incomes rose by 0.3 percent and spending by 0.2 percent. Over the past two years, U.S. households have managed to sustain their spending in the face of rising prices thanks to the record savings they built up over the pandemic. In recent months, it looked as though such savings might soon be exhausted. But as incomes rose in February, households started rebuilding their cash reserves, as the savings rate hit 4.6 percent, up from 3 percent last autumn.

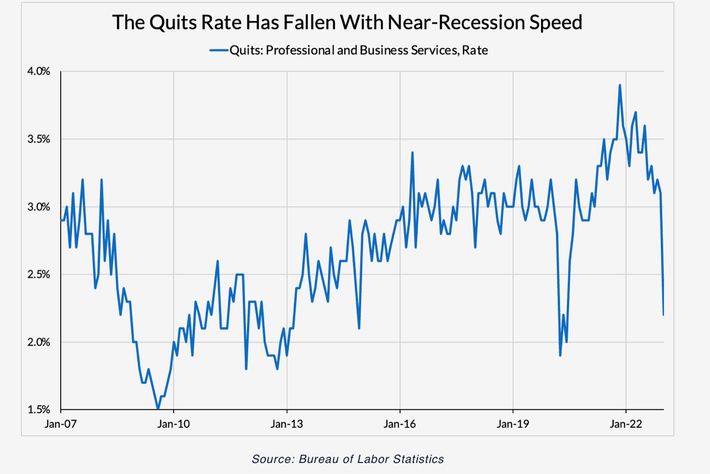

This said, there is usually a gap between the onset of an economic slowdown and widespread job losses, as firms generally look to cut other costs before shrinking payrolls. And there are some signs that the labor market might be weakening. New jobless claims rose modestly last week, even as the quits rate has been falling precipitously. The latter is a decent barometer for the labor market’s strength, as workers are far more likely to voluntarily leave their positions if they either have a job offer from another employer or a sense that job opportunities are abundant.

For now, many analysts believe that the U.S. is still likely to avoid a recession this year, with economists at Goldman Sachs putting the odds of a 2023 downturn at 35 percent, up from 25 percent before SVB’s collapse. But investors are betting that deteriorating economic conditions will force the Fed to cut interest rates as soon as this fall.

In sum, although federal intervention drastically reduced the costs of Silicon Valley Bank’s mismanagement, its full price may nevertheless prove steep.