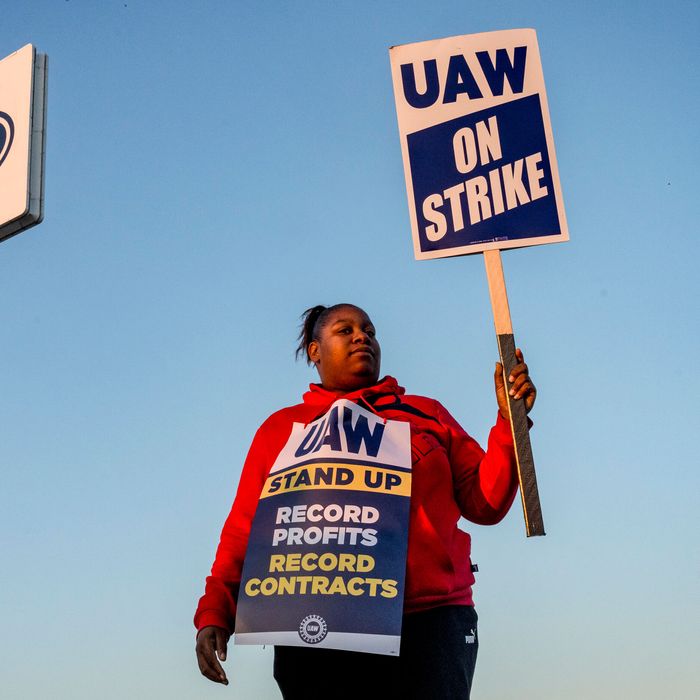

No one in the White House thought there was much subtlety to the message United Autoworkers leader Shawn Fain was delivering. His brushback was clear. President Biden had just announced he was sending acting Labor secretary Julie Su and economic adviser Gene Sperling to Detroit to help the three major U.S. automakers and Fain’s union reach a contract to end the first-ever simultaneous strike against the trio. But Fain was having none of it. “People are talking about them trying to interject themselves into our negotiations,” he said on CBS News last Sunday morning. “Our negotiators are fighting hard, our leadership’s fighting hard. It’s going to be won at the negotiating table with our negotiating teams, with our members manning the picket lines and our allies out there. Who the president is now, who the former president was, or the president before them, isn’t going to win this fight.”

For a president who likes to think of himself as “union Joe,” it was, to say the least, awkward. As the strike against Ford, GM, and Stellantis spreads wider, it is unmistakable to Biden that maintaining his support for labor means straddling a fine political line. As eager as he is to openly communicate to the autoworkers and the country that he’s on their side, especially as Donald Trump tries to elbow his way into the matter, he’s also hamstrung by the minimal public role the UAW wants him to play, even as anxiety rises about a prolonged strike’s economic ramifications — and by the fear that he may risk being dragged into an unproductive exchange with Trump.

The result has been an uncomfortable, but so far effective, political dance for the president. At the strike’s outset, Biden made sure his allegiance was spelled out in a brief speech at the White House. “Over generations, autoworkers sacrificed so much to keep the industry alive and strong, especially the economic crisis and the pandemic,” he said, announcing that he was dispatching Su and Sperling. “Workers deserve a fair share of the benefits they helped create.” Yet just as Fain’s comments two days later suggested his support was only so helpful, Trump jumped into the fray on Meet the Press. “The autoworkers are being sold down the river by their leadership, and their leadership should endorse Trump,” he said, just before word leaked that he would go to Detroit himself for a prime-time speech next week to counterprogram the next GOP-primary debate. Instead of rushing to match Trump’s visit, or to beat him there as some liberal allies hoped, though, Biden on Monday simply reversed his plan to send Su and Sperling to Michigan.

It’s not the first time Biden’s pledge to be the most pro-union president in history has spun into the national spotlight at a politically delicate moment. Two months into his term, he circulated a video expressing solidarity with Amazon-warehouse workers in Alabama who were trying to unionize; he did so only after determining it would be inappropriate to go even further and explicitly endorse their drive. More recently, he has opted against visiting the fundraising hot spot of Los Angeles for his reelection campaign because it would almost certainly mean appearing with Hollywood studio heads who are the focus of striking actors and writers. More painfully, last winter he intervened in what would have been an economically debilitating railroad strike, siding with most of the unions involved but disappointing others who were holding out for sick leave for their workers.

Still, the last week’s back-and-forth has given some Biden supporters in D.C. reason for concern that he is not as politically nimble or aggressive as they’d hoped ahead of a likely rematch against Trump, a worry that has sometimes dovetailed with the preexisting complaints about his age. As once again became clear when Biden resisted calls to visit East Palestine, Ohio, after the train derailment there in February, he disdains the idea of touching down in a crisis zone unless he can actually help — but he also detests the possible perception that he’d simply be chasing Trump to the scene.

Biden and his advisers had been confident that the union and most of its workers are ultimately supportive of him and skeptical of Trump and that they get that Biden backs them. Biden’s campaign responded to Trump’s statement impatiently: “Donald Trump will say literally anything to distract from his long record of breaking promises and failing America’s workers,” said spokesman Ammar Moussa. “Under Trump, autoworkers shuttered their doors and sent American jobs overseas. Under Trump, auto companies would have likely gone bankrupt, devastating the industry and upending millions of lives.”

By Friday though, the ground shifted. In a speech that morning, Fain invited “everyone who supports our cause to join us on the picket lines, from our friends and family all the way to the president of the United States.” Hours later, Biden announced he would do just that in Michigan on Tuesday, preempting Trump’s own visit to the state a day later.

Fain, for his part, appeared to recognize the immediate political twist Biden found himself in by Tuesday, when Fain issued a statement intended to knock back any talk of Trump as a worker savior. “Every fiber of our union is being poured into fighting the billionaire class and an economy that enriches people like Donald Trump at the expense of workers. We can’t keep electing billionaires and millionaires that don’t have any understanding what it is like to live paycheck to paycheck and struggle to get by and expecting them to solve the problems of the working class.”

Few of Biden’s longest-standing allies have been surprised, however, by the deference to the UAW leadership implied by his choice to keep Sperling and Su in Washington, let alone his choice not to head to Detroit himself. Biden has long made clear to aides that he always wants to be publicly seen as being on the side of labor, which has in turn largely supported him. This sometimes caused clashes with colleagues during the slow economic recovery of the first Obama term, when unions wanted more from him, and late in that administration he occasionally butted heads with aides who wanted him selling parts of Obama’s prioritized Trans-Pacific Partnership — which he believed would be outright opposed by big unions. More recently, he has shied away from grappling in much detail with a major auto-union concern: how his own push for electric vehicles will affect those workers’ jobs.

Nonetheless, it’s not as obvious as it might seem that Biden should want to be seen as in lockstep with the union on this particular fight, even as he has emphasized his labor ties in his 2024 campaign. The president, who often proclaims himself a “car guy,” has also been notably close to GM CEO Mary Barra in recent years: Politico reported this week that she has visited his White House eight times as he has worked on popularizing the transition to EVs.

And some prominent corporate-world allies have publicly cautioned against exuberant support for the UAW. Investor Steven Rattner, the Obama administration’s “car czar,” on Wednesday warned in the Times that while he sympathized with worker demands for higher pay, “this increasingly militant UAW is overplaying its hand with an overly lengthy and overly ambitious list of demands.” (Then there’s the fact that Biden’s niece works on sustainability issues at GM, which also counts Jeff Ricchetti, brother of one of Biden’s closest aides, Steve Ricchetti, as a lobbyist — though people close to the president bristle at the notion that any of this is relevant.)

Still, when it comes to labor matters, Biden is always more sensitive to his left flank. And in recent days, those around him have been more concerned with the opinion held by some Midwestern allies that the president hadn’t paid close enough attention to the build-up to the strike and that he was therefore unwarrantedly confident in the conflict’s quick resolution.

That’s one reason why this week’s relatively light public touch has been matched by a private insistence that officials like Su and Sperling keep close tabs on every twist of the negotiations. Biden has learned on multiple occasions throughout his term that strategic silence can be far more politically helpful than using his divisive bully pulpit; he has the tactic to thank for both the Inflation Reduction Act and the bipartisan gun-control legislation he signed last summer.

But just as when those negotiations dragged on, he now has his staff monitoring, just in case. There’s still a chance his voice might actually be helpful.