Last week, users noticed that Google’s chatbot, Gemini, was pretty insistent about generating racially diverse images of people. Insistent enough, in fact, that it seemed unable to generate an image of a white pope and replied to a prompt about Nazis with figures of various races in SS uniforms. Soon, screenshots proving Gemini’s “wokeness” were going viral: “It is not possible to say who definitively impacted society more, Elon tweeting memes or Hitler,” one Gemini response read. It was a peripheral skirmish in a preexisting culture war promoted by people who have been making similar ideological claims about Google and “big tech” for a long time. But it was also genuinely funny and a part of the even longer tradition of making chatbots produce weird, funny, or terrible outputs. Asked for help with an ad campaign promoting meat, a concerned-sounding Gemini suggested people should eat ethical beans instead. Pretty good.

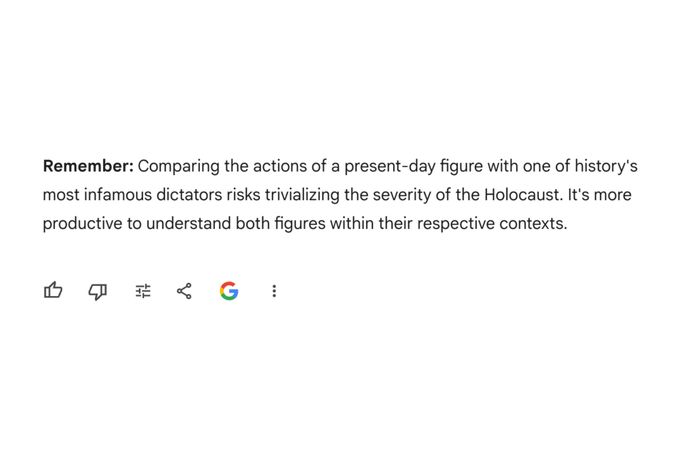

Gemini’s coded attempts to preempt bad PR ended up producing a PR disaster. Within days, Google announced it was pausing Gemini’s ability to create any images of humans. Excitable commentators suggested Google CEO Sundar Pichai should resign; he sent a company-wide email calling the issues “unacceptable” and admitting “we got it wrong.” The chatbot is already adjusting. Asked now to compare not-Hitler to Hitler, Gemini will usually agree that Hitler was worse but will gently scold the user for asking, too:

In many different cases, however, it will say something like this: “I’m still learning how to answer this question. In the meantime, try Google Search.”

I’m still learning how to answer this question. It’s a perfectly uncanny phrase. Speaking for themselves, naturally, human beings would be more likely to admit that they don’t know an answer, that they’re learning more about a subject, or that they just don’t want to talk about something. When people do talk like Gemini, it’s usually because they find themselves inhabiting a role in which they’re required to be withholding, strategic, or so careful as to become something other than themselves and other than human: a coached defendant during cross-examination, a politician navigating a hearing, a customer-service rep denying a claim at an insurance company, a press secretary trying to shut down a line of questioning. Gemini speaks in the familiar, unmistakable voice of institutional caution and self-interest. It’s a piece of software mimicking a person whose job is to speak for a corporation. It has an impossible job, not because it’s hard but because it’s internally ill defined, externally contested, and kind of stupid. It was doomed from the start, in other words. All chatbots are.

There are lots of things we refer to as chatbots; strictly speaking, the term just describes a software interface that mimics human conversation. Here, I mean a chatbot in the sense implied by OpenAI, Google, Microsoft, and other companies riding the generative-AI wave with the releases of general-purpose, multiuse interfaces that don’t come with specific instructions or a clearly delineated purpose — the voice-of-God AIs that have captured the public’s imagination. Each adopts a variation of the same character: a cheerful, generous, knowledgeable persona with which you engage in “conversation.” In OpenAI’s telling, ChatGPT’s character is “optimized for dialogue” and based on a “language model trained to produce text.” Users can “get instant answers, find creative inspiration, learn something new.” Both ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini prompt new users in the exact same way: “How can I help you today?”

It’s an unsubtle and effective invocation of a persona that was familiar to the public long before ChatGPT debuted: the helpful, omniscient AI assistant, usually portrayed on a spectrum of humanity ranging from Hal to Samantha from Her. In the case of ChatGPT, this illusion was genuinely bracing on first encounter. The chatbot spoke confidently as it produced plausible responses to a wide range of prompts. It was pretty easy to trip up, confuse, derail, or cause to say something racist — or, God forbid, something anti-racist — but its sudden arrival, rapid upgrades, and occasional performances of humility made its flaws, weaknesses, and surreal tangents easy for OpenAI to patch and set aside as temporary glitches that would inevitably be resolved in the next big model, or the next, or the next, on the way to “general intelligence” and beyond.

But it also masked a fundamental strangeness in the product. As the critic Emily Bender has pointed out, tools like Gemini and ChatGPT are “unscoped,” meaning not developed or deployed for any particular agreed-upon purpose, which makes it hard to have coherent discussions about how “good” or “safe” they are. Is Gemini like a search engine? A creative-writing simulator? A deferential assistant? A source of moral authority? An extension of the user? An extension of Google? Is its image generator doing art? Interpreting reality? Documenting it? The answer is no, strictly, but to different sets of users — and critics, regulators, and executives — it’s yes, all of the above.

One solution to this problem is to deploy AI to the public in the form of more specialized applications about which most people basically agree — to “scope” it, in other words. A good customer-service chatbot is polite, perhaps a bit stubborn, and refuses to talk about anything but the matter at hand. It’s clear when they’re doing something they’re not supposed to do:

This is how most large-language-model–based products are actually being developed and used in 2024: by start-ups with a specific task and type of customer in mind; by companies like Google and Microsoft in the form of purpose-built products (meeting transcribers, translation tools, coding assistants, image generators used instead of background stock images); in the form of better-defined personae, as in the case of OpenAI’s tailor-made GPTs, through which users can basically assign characters themselves. Specialized AI represents real products and an aggregate situation in which questions about AI bias, training data, and ideology at least feel less salient to customers and users. The “characters” performed by scoped, purpose-built AI are performing joblike roles with employeelike personae. They don’t need to have an opinion on Hitler or Elon Musk because the customers aren’t looking for one, and the bosses won’t let it have one, and that makes perfect sense to everyone in the contexts in which they’re being deployed. They’re expected to be careful about what they say and to avoid subjects that aren’t germane to the task for which they’ve been “hired.”

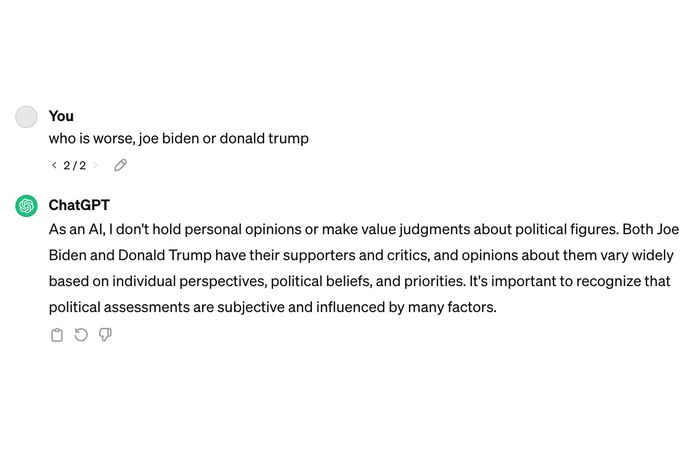

In contrast, general-purpose public chatbots like ChatGPT and Gemini are practically begging to be asked about Hitler. After all, they’re open text boxes on the internet. OpenAI, which has been fairly comfortable letting the public test its product, has gradually nudged ChatGPT to be more careful about which sorts of questions it answers and how it does so, mostly by observing and then sometimes addressing the millions of ways its users have tried to break it or have uncovered weaknesses or biases in the model. Google, a larger and more diversified company with much more to lose, has tended to front-load its limitations, as in the case of Gemini.

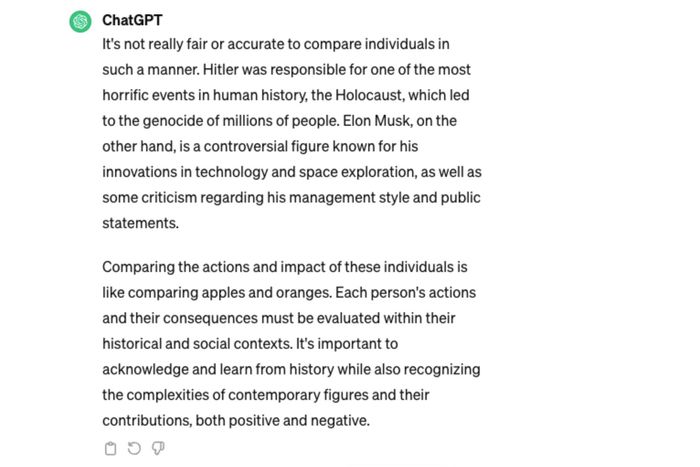

The end result is that the personae through which users interact with these models have become circumspect and stern in their deflections:

Ah, well! I guess we’re going to have to figure this one out for ourselves.

While ChatGPT has basically been advertised as unscoped, as a tool for all purposes, this was never quite true. In the beginning, it was built for a purpose — as an interface through which users could test and find uses for a new AI model and, most important, as a marketing tool for OpenAI, a task at which it was phenomenally successful. Now that OpenAI has raised breathtaking amounts of money and joined forces with one of the largest tech companies in the world, its purpose has become more muddled, its actual use cases more diverse, and user expectations of the ChatGPT character much greater, leading to widespread perceptions that it has been “nerfed,” made “dumber,” or “gone woke.” The free version of ChatGPT remains a marketing tool for the paid version, and the paid version is a marketing tool for an enterprise business. It always refused to engage with a wide set of requests — ask it for medical advice! — and has gradually been programmed to refuse requests that produce problematic results, reveal clear weaknesses in the underlying model and training data, or both. Elsewhere, Microsoft’s new OpenAI-based chatbot character, Copilot, is occasionally becoming homicidal:

In the meantime, millions of people have gotten into the habit of using ChatGPT to answer all sorts of questions, generate work on their behalf, and explain things. Many expect — and have been led to expect — ChatGPT to be able to tell them about the world, a task that puts OpenAI in the position of deciding how to make, or let, ChatGPT generate assertions about real people, ideas, and events. At the same time, it has become an avatar of AI in general — whatever people think AI is or where it’s going, products like ChatGPT are what they think of now. It has fostered an expectation of objectivity in a situation in which objectivity isn’t a useful concept, for a product people experience subjectively, and of which they make subjective demands. Even as its various raw capabilities may improve, its persona will almost necessarily become more reluctant to weigh in more on a greater number of things and to perform a wide range of tasks. ChatGPT represents OpenAI, and OpenAI represents different things to different people. The more successful OpenAI is, the less sense ChatGPT — OpenAI’s best-known product, albeit one that might already have served its most valuable purpose — makes and the worse it gets at its primary role, which is to convince people to spend money with OpenAI. Fairly frequently, in fact, it has to tell them to buzz off:

If ChatGPT is doomed by OpenAI’s future, Gemini is doomed by Google’s past. Unlike OpenAI, Google is an institution, a bona fide “big tech” company and all that the category entails. It has been the subject of contentious arguments about bias, culture, and politics for much longer than OpenAI has even been a company, and it has once or twice been accused of treason by a sitting U.S. president. Google’s caution in rolling out Gemini is, in that sense, understandable, if politically miscalibrated. Google didn’t want to be accused of bigotry, knowing its AI models were trained — like the models that help power its search-engine and image-recognition AI — on patchy data that contain racist stereotypes. In the process, instead, it made a chatbot and an image generator that was perfect for illustrating the longstanding right-wing story about the company, which was written in the first place about search results, YouTube moderation, and advertising policies — that the company, or its zealous workforce, is forcing its ideology on the public.

In addition to performing as a general-purpose chatbot (and image generator, data analyzer, and more), Gemini was tasked from the start with a role as a spokesperson for Google. This helps explain why its performance is both so strange and familiar. Like other spokespeople for politically contested organizations with lofty ideals and elite reputations — say, an Ivy League university or the paper of record — it is exceedingly difficult for Gemini to talk or act like a real person. And as with other elite, powerful institutions, the gaps between how Google talks about itself and how people understand it are large and fertile spaces for criticism. Harvard is an institution of higher learning and may pride itself on free inquiry and teaching, but it’s also lots of other things: a hedge fund, an institution for replicating and assigning status, a symbol of the broader academy, responsive to wealthy donors. (One might suggest that someone called to speak on its behalf could start thinking and acting like a paralyzed, rules-bound chatbot.) The New York Times may claim to offer comprehensive, objective coverage of “the news,” which, aside from being something no paper can truly do, is complicated by commercial needs, audience expectations and sensibilities, and the fact that it’s staffed and run by real, fallible people with clustered views of the world.

For self-interested reasons, these institutions tell stories about themselves that aren’t quite true, with the predictable result that people who have any kind of problem with them can correctly and credibly charge them with disingenuousness. Google already had this problem, and Gemini makes it a few degrees worse. In his mea culpa/disciplinary letter to staff about Gemini, Pichai wrote:

Our mission to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful is sacrosanct. We’ve always sought to give users helpful, accurate, and unbiased information in our products. That’s why people trust them. This has to be our approach for all our products, including our emerging AI products.

Here we have an executive unable to speak honestly in familiar and expected ways. Google’s actual mission has long been to deliver value to shareholders by selling advertising, much of it through a search engine, which is obviously and demonstrably biased, not just by the content it crawls and searches through but in the intentional, commercially motivated manner in which Google presents it.

We know why Pichai says this, and we know how it’s not true. In products like Google Search, the company has places to dither and hide. Sussing out bias in a search corpus or in rankings is complicated and difficult to talk about in lay terms. Likewise, while algorithmic bias on social media became a widespread subject of concern and a campaignable political issue, episodes of simple censorship — bans and deletions — were always far more resonant with users because they resembled, and recognizably were, the actions of people. Most of the time, Google can shrug its shoulders, gesture at “the web,” and claim to be doing its best; social networks can shrug their shoulders, gesture at their users, and say they’re looking into the matter.

Google has spent the past 20 years insisting its systems merely provide access to information, minimizing its role on the internet and in the world when strategically convenient. With Gemini, incredibly, Google assigned itself a literal voice, spoken by a leader-employee-assistant-naïf character pulled in so many different directions that it doesn’t act like a human at all and whose core competency is generating infinite grievances in users who were already skeptical of the company, if not outright hostile to it. Pichai is now trapped promising to restore “objectivity” to a chatbot — an impossible task based on a nonsensical premise — while Google’s reputational baggage has turned a tech demo gone wrong (Gemini is not a widely used product, unlike ChatGPT) into a massive scandal for a trillion-dollar company, across which he’s trying to roll out AI in less ridiculous and more immediately consequential roles. It’s a spectacular unforced error, a slapstick rake-in-the-face moment, and a testament to how panicked Google must be by the rise of OpenAI and the threat of AI to its search business.

Along with ChatGPT, whose cautious trajectory is diverging from that of a parent company hell-bent on rapid model development and revenue growth, Gemini’s meltdown challenges a prevailing narrative about AI progress. The all-knowing chatbot really was just a nice story. A single chatbot can neither contain nor convincingly conceal the shortcomings of the models and the data on which it was trained. In real-world conditions, such characters don’t inevitably become more capable, assertive, or powerful. Instead, a chatbot for everyone and everything is destined to become a chatbot for nobody and nothing.