In December of last year, Ariel, a 24-year-old content creator in New Jersey, received a message from a French digital-marketing company called Arcads. Ariel makes her living doing marketing videos for brands, who hire her through platforms like Fiverr and Upwork. Arcads had a slightly different request. “They asked if I’d be willing to take part in their AI technology campaign,” Ariel said. “They gave me a couple of prompts and said, ‘Talk as long as you can.’”

She sent them the material. Later, the company reps came back with feedback and specific requests for clips filmed in different environments. They wanted walk-and-talk video. They wanted different settings. They wanted her sitting in a car. It wasn’t that much work — nine videos in total — she was paid for it, and it felt like something new and interesting.

On Tuesday, months later, Ariel got a message from a friend with a link to a video posted on X. It had millions of views and thousands of responses and had become the subject of an intense and very strange debate between AI boosters, AI skeptics, and thousands of other assorted strangers with theories of their own. The preview contained her face. “Is this real?” her friend asked.

“When I watched the video, I genuinely thought it was one of my UGC (user-generated content) videos,” she said. The style, delivery, and location were all familiar. “I’ve done so many, I lose track,” she said, and companies post her influencer-style videos on their social-media channels all the time.

Then she listened to the text: an awkward, trollish rant about body odor and deodorant pitching a brand of cleaning wipes. She knew she’d never worked with this company and watched the video more closely. It was her, but not quite. She’d encountered her AI clone in the wild. “It honestly just threw me off a little,” she said. It had been a while since she thought about the AI company, and she hadn’t seen any of its work before this week. Now, through Arcads, clients were hiring an automated Ariel to do brand videos, and one of them had gone viral. Arcads had been honest about its plans, and Ariel felt she was fairly compensated and hadn’t been misled. Still, she said, “It just caught me off guard.” How couldn’t it?

What turned the video into the social-media controversy du jour wasn’t so much the video’s content as a couple of imprecise captions, which launched it into the center of the churning online discourse about the future of AI. First, there was the original, from the founder of the client company: “It’s terrible but I still think it’s wild that this can all be done with AI. Imagine in 6 months …” A classic social marketing post, honestly — vague and teasing, with an unclear subject-poster relationship and a strong connection to an unrelated trend. From there, it got picked up by a bunch of AI influencers, whose breathless posts (“It’s so over …”) really took off:

Linus Ekenstam’s post started drawing skeptical responses from his audience of AI optimists and doomers. This clearly wasn’t AI, some said, in the sense that it wasn’t generated by AI from scratch — even the most advanced unreleased video-generation software from OpenAI can’t do something quite like this. Others decided that the post was fake, by which they meant the video it contained was not fake. They found Ariel’s Fiverr page, shared similar videos that she’d made, and concluded that the clip was a commission masquerading as a digital avatar. “I’ve gotten so many people messaging me on Fiverr and on Instagram asking if I’m real,” Ariel said. “People I’ve worked with in the past!”

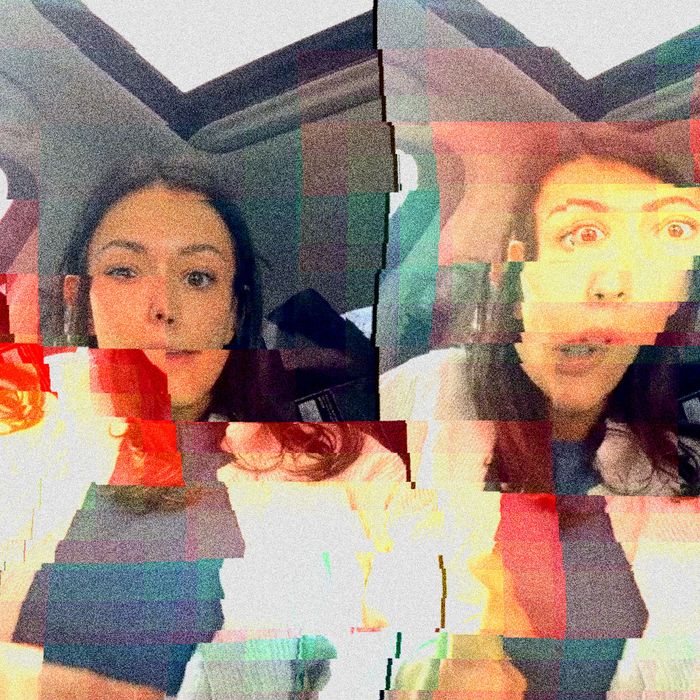

In comments and community notes, people, including Ekenstam, sorted things out: The video wasn’t entirely AI-generated, in the sense that the base imagery is real video of a real person, but the facial movements and voice were synthesized. Users started commissioning weirder, glitchier videos from cyber-Ariel (the caption here is misleading — the actual cost of the video was €10):

Still, lots of viewers remained unconvinced, or rather, quite convinced of whichever theory of the video they’d settled on before the video scrolled off their phones forever.

To AI enthusiasts, this sort of thing is old news. Arcads isn’t a big player in AI — this week’s attention crashed the service, and its main proposition seems to be collecting and digitizing UGC professionals into a stable of licensed talent — but its product is based almost entirely on technology from HeyGen, which has been available to the public since last year and which just raised a round of funding at a $440 million valuation.

HeyGen offers characters of its own that users can use to make corporate videos, ads, or anything else that needs a talking head. Crucially, it also has the ability to create puppet avatars from short clips, a feature I tested out a few months ago. From 30 seconds of grainy, poorly lit webcam footage, it synthesized a slightly robotic avatar with my upper body and face, something like my voice, and an unrecognizable but semi-plausible set of facial movements. Nobody I know would confuse it for me, but in the right context, they might confuse it for a person. This week, in The Atlantic, Louise Matsakis described the bracing experience of seeing her own HeyGen avatar speaking in perfectly translated Chinese. “By merely uploading a selfie taken on my iPhone, I was able to glimpse a level of Mandarin fluency that may elude me for the rest of my life,” she wrote.

HeyGen is a real company with customers who see some opportunity in creating what are basically sanctioned corporate deep fakes: individualized videos from executives to clients, customized video and email ads, internal communications, and seminars. (If you want a picture of the future, imagine an uncanny AI avatar leading a workplace harassment-training module about reading subtle social cues, forever.) What HeyGen does, and what Arcads is doing with HeyGen, also represents a safe-for-work, aboveboard take on a technology that lots of people find distressing, or worse, for a variety of reasons. Nonconsensual explicit deep fakes are now so easy to make that they’re a problem not just for public figures but at middle schools. Phone scammers are recording short conversations and then using voice synthesis to target family members. The ease with which record companies and movie studios can capture and reproduce digital likenesses — voices, faces, bodies — has artists rightfully worried and was a major issue driving last year’s Hollywood strikes. The existence of HeyGen demonstrates how accessible this sort of thing has become. Anyone who posts videos to TikTok, Instagram, or YouTube is providing more than enough training material for someone to make a pretty good clone.

Having the subject onboard, as Ariel was here, doesn’t resolve the essential strangeness of what’s going on or account for how people actually consume and encounter media. A simple ad turned into a disorienting and frequently nasty argument between thousands of people, for an audience of millions, not just about whether or not the video was real, but about what it even means to be real, eventually scattering participants across a range of conclusions from approximately “everyone has lost their minds about this” to “we’re all going to die.”

The video’s short trajectory tells a slightly different story than the one you commonly hear from politicians, experts, and pundits about deep fakes and disinformation: While people will certainly be manipulated by AI-generated political content, the more significant consequence of this technology will be that it sows doubt about everything else, establishing a conspiratorial default around videos of people in general.

There are clear limits to HeyGen’s technology as it exists today, and while it will certainly improve, it’s unclear by how much and at what. It’s good enough to create plausible marketing videos, so long as their audiences aren’t too familiar with the actor. Ariel isn’t primarily an influencer, in that she isn’t selling clients access to an audience. Instead, they post her videos themselves, for audiences that understand her as something between a spokesperson, a reviewer, and an influencer that they don’t know, but assume others do. The baseline artificiality of this arrangement would seem to make it a better target for automation, which companies like Arcads clearly think it is. Ariel, surprised as she was by the video, isn’t concerned. “It will definitely automate some things,” she said. “But I’m not worried about competing with myself — I’m a completely different being than that AI version of me,” she said. “It can’t do the same hand gestures or the various different things that make me me.”

So far, Ariel’s first encounter with self-automation has gone the other way — the video’s meta-virality has resulted in more business. “It’s weird, but I am grateful for it because so many more people have reached out asking if I can make videos for them. It’s boosted my profile,” she said. She’s still working with Arcads. “I have a very animated personality, and people saw that, and they were interested.” She’s booking a lot of fresh work on Fiverr and is now talking with the founder of the wipes company, whom she hadn’t been in contact with before, and who wants to keep riding this wave. Ariel is now “the new face” of the brand, she said, and they’ll be making videos together, this time with a camera.