In 1977, when Eman Soudani was 17 years old, her older brother Moutz invited her to move from Amman, Jordan, where they’d grown up, and live with him in New York. She had one year left in high school, and she pictured herself getting her diploma in the States and then enrolling in college. Moutz, who had emigrated 11 years earlier, promised he would pay her tuition.

Eman didn’t know much about her brother; she had been so young when he left. But the life he told her he created for himself sounded impressive. He had a wife, Helen, and three children. Since arriving in the U.S., he had worked in restaurants and now owned one just outside the city; important people ate there. Late that summer, Eman arrived in Spring Valley, a Hudson Valley village where, she says, almost immediately Moutz began abusing her. That abuse would continue for nearly five decades. Her brother, Eman says, treated her like a slave, forcing her to clean his house, raise his children, cook his food, and work at his restaurants for free. When she needed money, even for groceries, she had to ask him for it. More horrible still, she says, her own brother beat and raped her for years on end. (These and other allegations are part of a civil lawsuit Eman filed against Moutz in 2023 for sexual, physical, and financial abuse.) She didn’t know who she could safely turn to, given Moutz’s relationships with all of his important friends, a boys’ club of cops, attorneys, and politicians whom Eman regularly saw at his restaurant.

Still, in October 2022, just over 45 years after she arrived in the U.S., Eman left. She drove to Colorado, where she moved into a family member’s condo. Though she was finally more than a thousand miles away from her brother, she couldn’t relax. “He would tell me, ‘Don’t even think of leaving. Wherever you go, I will find you and I will hurt you,’” Eman says. For weeks, she rarely left the condo. Five months later, Eman was having her morning coffee in the kitchen when she heard a banging at the front door. A police officer told Eman they were executing a search warrant and asked her to step into the hallway. She was in her pajamas, her black hair, usually worn in a perfectly symmetrical bob, still messy. Standing in the hallway, Eman saw someone she recognized among the cops now flooding the condo. Walking toward her was Stewart Rosenwasser, a bald county prosecutor from New York, a member of Moutz’s boys’ club. Eman felt a clutch of panic. She realized that her brother had come for her.

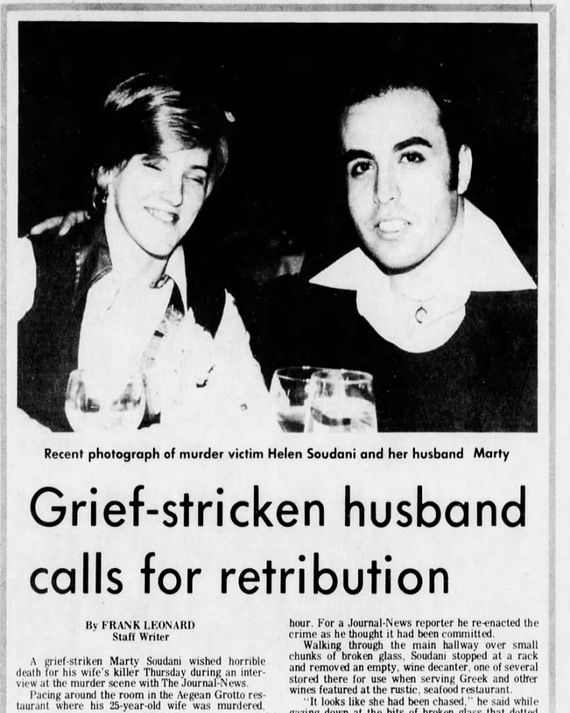

When Eman first arrived in Spring Valley, Moutz kept his promise to enroll her in high school. It was suburban and preppy — Eman, shy and not yet fluent in English, stuck out. She stayed up late studying, poring over textbooks and making vocabulary flash cards. Moutz and Helen took turns staying home with her and the three children at night and closing up at Aegean Grotto, the seafood-and-steak restaurant the couple had opened a few years earlier in a shopping center nearby. One Tuesday night, a few weeks after she arrived, Eman was up studying when she realized that neither Moutz or Helen was home. Later, she passed Moutz lying on the couch, his young son sleeping on his chest. Moutz turned to her and said something strange. “Eman, I was here all night, right?” He repeated the question until it was a command. “I was here all night, right? I was here all night. You tell everybody: I was here all night.”

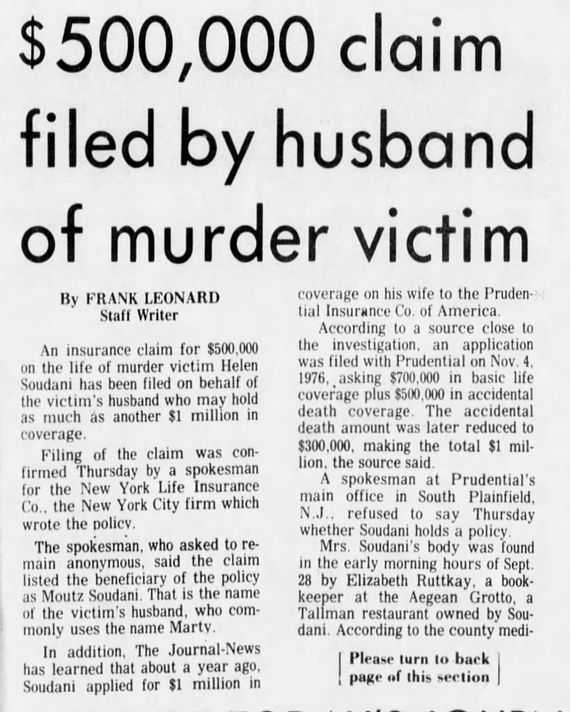

The next morning, Eman learned that Helen had been found beaten and strangled to death on the dining-room floor of Aegean Grotto. Police suspected Moutz immediately. A cook reported overhearing him tell Helen “that if she didn’t straighten out, he would kill her some day.” After the murder, the same cook had overheard Moutz say, “I didn’t mean to kill my wife.” But Moutz told detectives that he’d been at home that night, and when they questioned Eman, she backed her brother up. No one was arrested, and within days, Moutz started filing claims on Helen’s two life-insurance policies, both taken out in the year prior to her death, which together were worth more than $1.6 million. (Moutz, through his attorney, said every fact in a list of queries sent before publication was “false, inaccurate, or contain [sic] baseless allegations.” In court filings, he has claimed Eman “consented” to her living arrangement and that she was not sexually abused. He also denied murdering Helen.)

With Helen gone, Eman and Moutz’s relationship took a sharp turn. Moutz insisted Eman drop out of high school — someone, he reasoned, needed to take care of his children. He became increasingly hostile, telling Eman that she had brought bad luck on him, that she was a “jinx,” that Helen’s death was her fault. One night, not long after Helen’s murder, Eman says Moutz slid into bed next to her. When Eman objected, Moutz claimed he had made a mistake — that for a moment, he thought she was Helen. But several months later, Moutz did it again. This time, he allegedly raped his sister. “This is the price you have to pay,” Eman remembers him saying.

Soon after the murder, Moutz shuttered Aegean Grotto and eventually bought a one-story white-brick house in Montgomery, a hilly farm town west of Newburgh that includes three villages. Eman watched as Moutz reinvented himself. He bought a BMW and began wearing expensive suits. He opened a restaurant in the Ramada Inn in Newburgh and then, in 1986, another, called Soudani’s Cafe & Bistro, in Walden, one of Montgomery’s villages. With its mirrored walls and white linen tablecloths, along with the piano player Moutz brought in on weekends, Soudani’s quickly became the best place in the area to get a decent meal with some ambience. Steve Brescia, who would spend more than three decades as mayor of the Village of Montgomery, began coming in often, as did Jack Byrnes Jr., a cop who would soon become chief of Montgomery’s police department, and Stewart Rosenwasser, a private-practice attorney active in the county’s Republican Party. Moutz promoted Soudani’s as “the best of Las Vegas and Manhattan,” and the bar stayed open late. Often, Moutz’s regulars would gather until the early-morning hours, when Byrnes might step behind the bar to start mixing drinks. Above Soudani’s, Moutz rented out a few apartments and used a room to throw debauched parties where sex and drugs were openly enjoyed. “Nothing good was coming out of that building,” says Daryl Carr, a Village of Walden police officer during Soudani’s heyday, from the mid-1980s to mid-1990s. “Most of us went to Soudani’s at one time or another back in the day,” Brescia told me. “I remember going to a couple parties there, but I didn’t stay too late myself. They liked to party back in the day a little bit.”

Moutz reveled in his role as Walden’s night mayor, bragging to friends that he was rich, famous, and powerful. He was emboldened by it, too. “When somebody pushed back against Moutz, he didn’t like that. He had his own way of dealing with things,” says Carr. In 1990, Moutz had a dispute with Michael Bailey, a 20-something Montgomery resident who knew Moutz’s 17-year-old son. It’s unclear what set Moutz off, but he allegedly drove to Bailey’s house and attacked him, beating him with a baseball bat. While there were multiple eyewitnesses, the affair was resolved in Moutz’s favor over the next few months. Rosenwasser, the attorney who frequented Soudani’s, posted his bail, then unearthed four people willing to provide an alibi for Moutz, including Byrnes and Bob Bennett, another cop. The judge — who’d once played on the same baseball team as Rosenwasser — threw the case out entirely.

Moutz was more than just Montgomery’s best host. Among the regulars at the restaurant, he developed a reputation for giving out loans and operating something that resembled a check-cashing business. “If someone needed 50 grand, he was a guy who could go home and come back 20 minutes later with cash,” says someone who knew Byrnes and his friends. Moutz kept hundreds of thousands of dollars at the home he shared with Eman — he even had a safe installed beneath his living-room floor. In the 1990s, his wealth had grown substantially. By his own estimate, he was worth more than $4 million. He considered himself a benevolent financier, handing out $5,000 to Bennett and more than $15,000 to Byrnes, making campaign contributions, and investing in his friends’ side hustles. It’s unclear exactly where the money came from, though of course he had Helen’s life-insurance payouts, and he invested in the stock market and real estate, buying up properties upstate and abroad, including a pair of mini-mart gas stations.

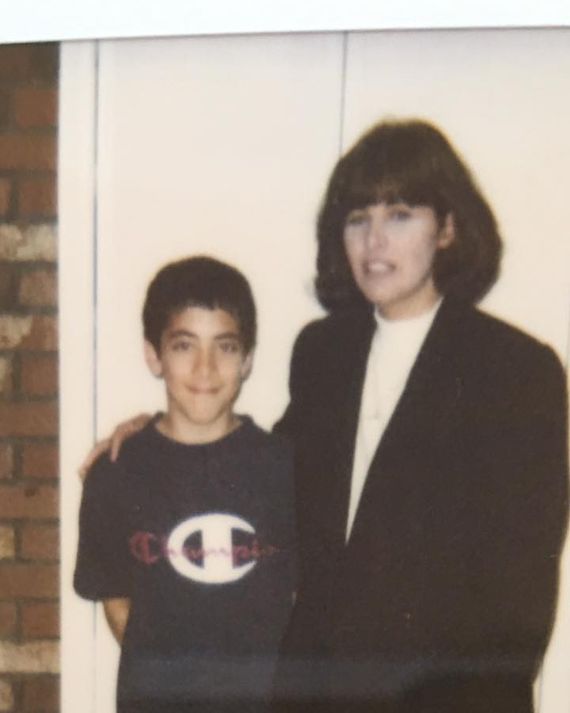

A few years after arriving in Montgomery, Eman gave birth to a son, Martin. Moutz sometimes called Martin his son, but Eman says he’s not. Moutz, she says, forced her to marry a man who left her once she got pregnant. This period of her life — when Martin was young and Moutz was running Soudani’s — was an especially terrible blur. Eman was immobilized by shame and fear. In her lawsuit, Eman claims Moutz called her a whore and took care to wall her off, threatening to beat her if she dared to make friends. Once, she claims, he ripped off Eman’s bedroom door and took an ax to her furniture. For almost two years, she slept on a mattress on the floor, hanging a sheet as a door. “I thought I was basically nothing,” she says. Escaping was unthinkable. Eman believed Moutz had gotten away with killing his wife, so what was stopping him from killing his sister? Eman helped balance Moutz’s ledger; she knew who accepted Moutz’s loans. “I saw how powerful he was around people. He always had something on someone. His connections scared me from trying to leave,” she says.

Orange County has always had a problem with graft. In the 1980s, it was widely understood that organized-crime outfits bribed town and county officials to allow them to dump toxic waste in landfills, some of which drained into the Wallkill River. More recently, a former county executive — the county’s highest elected official — pleaded guilty to public-corruption charges after he was caught awarding contracts to a company that paid him a salary for a no-show job. Last year, the current county executive’s office was subpoenaed by the FBI in connection to no-bid contracts, though no charges have been filed to date. It’s gotten bad enough in recent years that Orange County district attorney David Hoovler issued a statement broadly calling on officials to show some integrity. “Residents are entitled to honest government,” he wrote. “Those who work in a public capacity should be doing so for the benefit of all, not to help themselves or their family members.”

Various people who hung around Soudani’s were occasionally called out for ethics violations — as when Bennett, one of Moutz’s alibi witnesses during the beating case, was caught clocking in for jobs on two different police forces at the same time — but for the most part, the Soudani crowd proved untouchable. When the local newspaper, the Times Herald-Record, reported on a strange incident in which someone pulled a knife on Byrnes at 4 a.m. in his own home and only got a ticket, the reporter, Oliver Mackson, wondered why Brescia gave Byrnes a raise afterward. “Montgomery is one of those places where some people can do no wrong,” Mackson wrote. He referred to Byrnes and Brescia as Montgomery’s “Good Ol’ Boys.” A few cops in the Orange County Sheriff’s Office had another, more regionally appropriate nickname for them: the Montgomery Mafia.

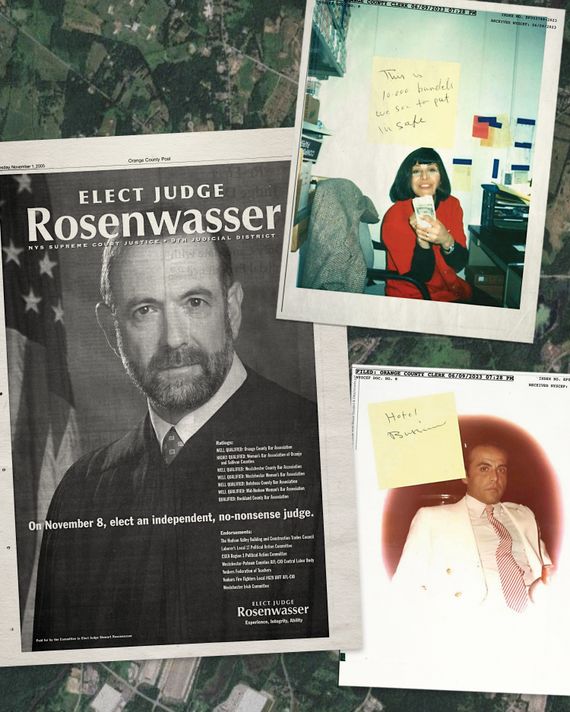

No one would have predicted that Stewart Rosenwasser would end up being the most corrupt member of the Montgomery Mafia. Though he’d grown up in Walden, he was older than Byrnes and Brescia, and by the time Moutz opened Soudani’s, Rosenwasser was on his way to being a well-respected litigator. He toiled away at DWIs and divorces (he represented Byrnes in the latter and Brescia in both) as well as real-estate transactions (handling many of Moutz’s and Brynes’s deals) and the occasional high-profile criminal case. (In 1996, he defended Chris Colombo, crime boss Joseph Colombo’s son, against gambling charges.) His practice was successful. By the 1990s, Rosenwasser lived with his wife and three children in a 4,500-square-foot home, which he remodeled, adding an inground swimming pool and, later, an attached three-car garage. He coached Little League and was politically active; he was chair of Montgomery’s Republican Committee and hosted phone banks for the party at his law office, which was not far from Soudani’s. When Rosenwasser offered to work as attorney to the Montgomery town supervisor, Susan Cockburn, a Democrat in a heavily Republican region, he sold himself by claiming that, being Jewish, he knew what it was like to be an outsider in their community. “But he was really no different than the rest of them,” Cockburn says. When Rosenwasser ran for county court judge in 1999, one resident wrote a letter to the newspaper decrying his relationship with Brescia: “Won’t a vote for Rosenwasser be a vote for more ‘clubhouse’ justice?”

Rosenwasser won that race and took his oath of office in December 1999. County judges spend most of their time presiding over criminal cases, and soon after he was sworn in, Rosenwasser sentenced two 17-year-olds convicted of robbery as adults, giving them each five-year prison sentences, despite both being first-time offenders. For this, Mackson, the local reporter, coined a nickname for Rosenwasser that stuck: “Maximum Stew.” And yet, within a few years of taking the bench, rumors began to circulate that Rosenwasser was selling acquittals in bench trials. Two attorneys told me that Rosenwasser solicited bribes from clients they had represented. In one instance, Byrnes, speaking on Rosenwasser’s behalf, offered an acquittal for a price. “We told him to go fuck himself,” says the client’s attorney.

In 2006, Rosenwasser abruptly quit the bench, barely halfway into his ten-year term. He told a reporter that his low salary was one reason for his resignation. But in the years that followed, his name popped up in a handful of investigations. “I consider it to be the biggest secret that I’ve ever had in my life,” says Peter Kulkin, a former Newburgh city court judge who once signed a search warrant related to a bribery investigation into Rosenwasser. “There had always been rumors, even before he was a judge, and when I saw the warrant, I’m like, Holy shit, Rosenwasser has committed crimes.” Around 2011, a defendant in a criminal case told investigators from the Orange County DA’s office and the FBI that he’d once paid Rosenwasser for an acquittal in a DWI bench trial, according to two people familiar with the interview. But the investigations stayed in the realm of gossip. So, his reputation intact, Rosenwasser thrived in private practice, where, as a former judge, he was one of the highest-profile attorneys in the county. He partnered with Ben Ostrer, a well-respected defense attorney, and the two expanded. In 2008, they hired an ambitious 39-year-old former Orange County prosecutor named David Hoovler.

Hoovler proved helpful to Rosenwasser and Rosenwasser to Hoovler. When, in 2013, Hoovler ran for DA, Rosenwasser threw his support behind his campaign. In turn, once elected, Hoovler named Rosenwasser to his board of advisers and hired both Rosenwasser’s son and his future daughter-in-law as assistant prosecutors. In 2019, Hoovler went a step further, hiring Rosenwasser to be one of the highest-ranking prosecutors in his office. Hoovler gave Rosenwasser a portfolio that included oversight of compliance with state criminal-justice initiatives and a handful of sensitive cases. “The public good is surely advanced when a lawyer of Judge Rosenwasser’s caliber and ethical standards agrees to continue in public service,” Hoovler said in a press release announcing his new prosecutor.

It wasn’t long before a case involving one of the Montgomery boys crossed Rosenwasser’s desk. In 2021, Rosenwasser secured three guilty pleas related to corruption charges, including one from a well-connected former Orange County executive, Edward Diana. As a county legislator, Brescia had nominated Diana to the board of the county’s Industrial Development Agency, and Diana went on to vote in favor of awarding lucrative contracts to a company that was paying him a salary for a no-show job. However, even with corruption admissions in hand, Maximum Stew, as many people still thought of him, didn’t seek jail time. Instead, Diana pleaded guilty to two misdemeanors and was required to pay restitution. (According to a report summarizing the investigation, Brescia admitted to learning about Diana’s conflict, only to forget about it later.) Even some of Rosenwasser’s fellow Republicans questioned the decision.

By the 1990s, Eman no longer needed to look after Moutz’s children. Two left the house on Bailey Road as soon as they could, and one died in a car accident. Soudani’s closed, but Moutz continued to find other ways to make money, sometimes involving Eman and Martin. The understanding was that everything, no matter what, was “family money,” as Moutz called it. Eman knew that meant Moutz controlled it all. In 2018, Eman was 58 and both she and Martin, 33, were still living in the house with Moutz. That year, after Eman was involved in a car accident, Moutz insisted Eman file a lawsuit against the driver of the other car. Eman eventually won a $62,000 settlement, but Moutz was sure the money was funneled into a bank account he controlled.

Even after the restaurant closed, Moutz maintained his ties to the Montgomery Mafia. He loaned Brescia money and contributed to Byrnes’s campaign when he ran for Montgomery village justice in 2019. (Byrnes died in 2019. Brescia resigned from the county legislature in 2021 following a sexual-harassment investigation. He is presently the Montgomery town supervisor.)

Those connections came in handy when, in the fall of 2022, Martin fell out of line. Moutz had asked his nephew to invest a million dollars in crypto, but instead Martin allegedly transferred the funds into a Coinbase account to which Moutz didn’t have access. On October 11, Moutz and Martin got into a scuffle. Someone called the police, and Martin was arrested and served with a restraining order. It was a few days later that Eman and Martin left the house for Colorado, without telling Moutz, allegedly taking with them hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash.

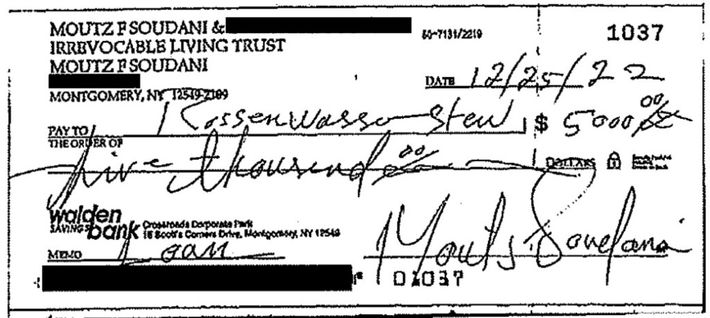

Moutz went to Rosenwasser for help. He wanted him to open a criminal investigation into Martin and Eman. He didn’t just want his money back; he wanted to punish his nephew and sister. And as he told a friend, Rosenwasser owed him money: $40,000 for an old loan. “The DA’s on my side,” Moutz told his friend. On November 10, 2022, Rosenwasser met Moutz at the Goshen Diner, a lunch spot popular with the county’s attorneys and judges, to go over the details of Moutz’s case. Rosenwasser needed Moutz to provide bank records that supported his allegation that Martin had stolen his money. That same day, Rosenwasser deposited a $15,000 check from Moutz with the word “Loan” written in the memo. Over the next few months, Rosenwasser and Moutz communicated frequently, texting, talking on the phone, or meeting in person. (Between November and December, they exchanged at least 200 texts and 26 phone calls.) Moutz supplied Rosenwasser with bank records that allegedly showed Martin moving Moutz’s money. “Believe me. I’m putting maximum effort into this,” Rosenwasser wrote to Moutz, who was thrilled that his old friend was putting together a case so quickly. “You are a genius and tuff as nails with your calm voice and that smile on your face you could go through steel,” Moutz wrote back. “I will always protect you,” Rosenwasser replied.

Rosenwasser occasionally expressed concern about the digital trail he and Moutz were creating, but they never stopped texting. By late February, Rosenwasser had located Eman and Martin in Colorado and gotten a search warrant for the condo where they were living. Though prosecutors don’t often participate in search warrants, Rosenwasser decided to travel across the country for this one. “When Eman sees me, it’s over,” Rosenwasser texted Moutz. The day before the raid, Moutz sent Rosenwasser another request. He wanted footage of the search. “I want to see them humiliated,” he wrote. “I can’t sleep, my stomach is full of butterflies.” Rosenwasser promised Moutz that he would get the body-cam footage for him.

That footage shows the moment Eman, having been told to wait outside the condo while police rifle through her belongings, sees Rosenwasser walking toward her in the hallway. Her eyes harden. “Really? Rosenwasser? Me? Shame on you. Why are you coming after me?” She points a finger at Rosenwasser. “Shame on you. I’m your friend. I made you food. You know why I left? I was getting beat up every single day. You want the truth?” Smiling, Rosenwasser tells Eman to calm down. She tries to look directly into Rosenwasser’s eyes, but he looks away, awkwardly grinning at the local cops standing around them. “After 45 years of abuse,” Eman says. “Shame on you. Only one-sided. Because everybody is bought,” she says. “You all cover up for each other. All of you.”

“I don’t work for him,” Rosenwasser says, presumably referring to Moutz. When a cop asks Eman if her dogs bite, Eman can’t hide her contempt. “I hope so,” she says. “I hope they bite the shit out of all of you.”

Eman was arrested and charged with grand larceny. A Colorado attorney referred her to a former prosecutor in Manhattan, Arthur Middlemiss, a partner at a boutique firm that specializes in complex cases involving international money laundering, bribery, and corruption. Middlemiss quickly picked out the flaws in Rosenwasser’s case. Not only was the prosecutor’s relationship with the Soudani family a blatant conflict of interest but also his entire case was predicated on an accusation leveled by a man who had allegedly physically and sexually abused the defendant for decades and who was also the prime suspect in his wife’s unsolved murder.

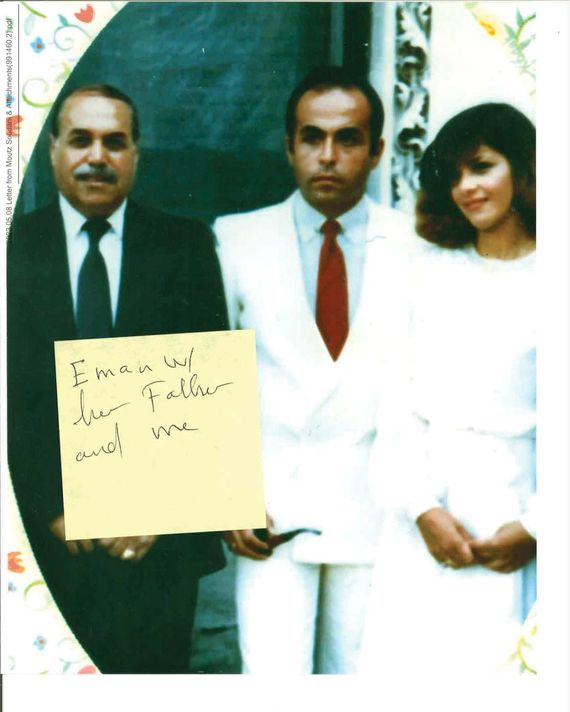

For his part, Rosenwasser was intent on seeing the case through; willing, even, to lie. For months, Rosenwasser denied so much as knowing Moutz. He also refused to set up a meeting between Eman and a sex-crimes prosecutor in the DA’s office unless Eman met with him first. Meanwhile, in early May, Moutz began writing to Middlemiss directly. He boasted about his history of getting criminal cases dismissed. “Don’t forget I am a 74 year old man who has been living in upstate New York for 40 years,” he wrote. “Everyone idolizes me and respects me to the fullest.” He attached photos of himself as a young man dressed in tightly tailored white suits and newspaper clippings about Soudani’s Cafe. Moutz also reached out to Eman, texting her: “Swear to God I wanna fucking choke you with my own hands you deserve a fucking beating like you never had before.”

Finally, in June, three months after Middlemiss first raised Rosenwasser’s conflict of interest, it seemed that Hoovler removed Rosenwasser from the case. His replacement, Chris Borek, agreed to hear Eman’s story. At the Orange County DA’s office, in the presence of a sex-crimes prosecutor and a social worker, Eman recounted in graphic detail the sexual and physical violence she says Moutz inflicted on her. After she left, the details of that meeting were relayed to Rosenwasser. He waved them off. “Middlemiss is full of shit,” Rosenwasser wrote to Borek. “I’m starting to feel like I’m getting forcibly raped.” Moutz was apparently also briefed on the meeting. “The investigators didn’t believe a word you said,” he wrote to Eman. “You’re full of shit.”

But something changed at the DA’s office after that meeting. Over the summer of 2023, when Rosenwasser asked an investigator for access to evidence related to the case, Borek blocked him. And in September, the DA’s office dropped its case against Eman entirely, claiming it didn’t have enough evidence. (Two months later, Martin pleaded guilty to grand larceny; he was given one to seven years in prison and was also ordered to return $1.6 million to Moutz.) The failed prosecution did little to ding Rosenwasser’s reputation. Two weeks later, Hoovler, who is up for reelection this year, posed for a photo alongside Rosenwasser, who was accepting an award for Outstanding Law Enforcement Executive.

Eman was galvanized by this turn of events, and soon after, Middlemiss filed a civil suit in federal court accusing Moutz of decades of abuse. The suit details Eman’s allegations that Moutz repeatedly raped her, sometimes using date-rape drugs, which Moutz had in “large quantities.” It claims she had an abortion after Moutz impregnated her and includes her belief that Moutz killed Helen, magnifying her sense that Moutz “would not hesitate to kill her if she did not obey him.”

During discovery, Middlemiss found that Moutz had been cutting checks to Rosenwasser at each milestone in the investigation into Eman: as Rosenwasser made progress with the search warrant; after Eman’s arraignment; after Moutz testified before the grand jury; after Moutz received a restitution check from the DA’s office. Standing outside Eman’s condo, Rosenwasser had told Eman that he didn’t work for Moutz. In fact, by that point, he’d already taken at least $25,000 from him. Middlemiss forwarded the evidence to the FBI, which launched an investigation. In June 2024, Rosenwasser sat for an interview with federal investigators. Three days later, on a Saturday morning, he resigned via email.

To an outsider, it might have seemed like a natural time for Rosenwasser to ride off into the sunset. He was 72 years old, and his three children were all grown up. But over the summer, as the details of Eman’s lawsuit made their way into local headlines, and the FBI’s investigation progressed, those who knew Rosenwasser began to worry about him. He seemed distraught, erratic. One longtime friend tried to convince him to give up any guns he kept at home. Before he retired, Rosenwasser and his wife traded their four-bedroom house for a two-bedroom carriage house shaded by tall white pines in a 55-plus community nearby. That’s where he was the morning of September 24, when FBI agents moved in to arrest him for bribery, wire fraud, and making false statements. According to local news reports, Rosenwasser answered the door holding a gun, which he pointed at an FBI agent. The agent fired a shot at Rosenwasser, who then barricaded himself inside. When police breached the barricade, they found Rosenwasser dead. According to the FBI, he died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. That same morning, a few miles away, the FBI arrested Moutz at an apartment he had moved to in Montgomery, also charging him with bribery, wire fraud, and making false statements.

At a recent bail hearing in White Plains, Moutz, wearing black sweatpants and Crocs, hunched over in his chair while his attorney, Michael K. Burke, discussed the terms of Moutz’s bail package. Federal judge Cathy Seibel was troubled that, despite Moutz living in Montgomery for so long, the only person willing to sign his bond was a tenant. “His only friend on the planet — his only friend in the country is a tenant?” The members of the Montgomery Mafia — whom he had spent decades loaning money to — were either dead or unwilling to help.

Eman, still in Colorado, didn’t feel especially relieved when she learned of Moutz’s arrest, or when police showed a renewed interest in Helen’s unsolved murder, or when the State Supreme Court vacated Martin’s conviction. The lawsuits, the criminal investigation, Rosenwasser’s death, the charges that could put Moutz behind bars for the rest of his life — none of it has quieted the incessant dread she feels. Her brother is alive and he is capable of anything. “I haven’t gotten a chance to breathe or start a new life,” Eman says. “I still live in fear.”