The story of TikTok has always been complicated by its ownership. When its predecessor, lip-syncing app Musical.ly, broke through with children and teenagers in 2016, the New York Times noted it’s “not easy to tell Musical.ly is Chinese — and that’s deliberate.” When the app was acquired by ByteDance and merged into the TikTok brand, Reuters reported the move as an act of concealment: “China’s ByteDance Scrubs Musical.ly Brand in Favor of TikTok.”

As TikTok grew, putting U.S. social-media giants on defense, it started taking heat for how it handled child safety, free speech, addictive behaviors, and marketing. Each critique was familiar — Facebook was still recovering from massive backlash — but informed this time by the question of foreign ownership, which provided a way for competitors, lobbyists, critics, and lawmakers to suggest something strange, sinister, and unknowable was going on with this wildly popular new app.

But TikTok’s rise has been haunted by another specter, invoked in similar ways and sometimes in the same breath: “the algorithm.”

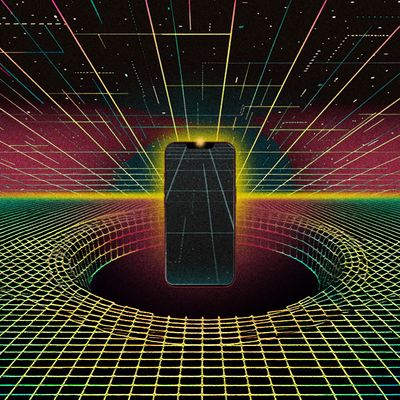

Early attempts to explain TikTok’s success in the press referred to its “secret sauce” — an algorithm that helps it “read your mind,” a “black hole” at the center of a platform that has kept “hundreds of millions of users worldwide hooked.” Now, with the federal government attempting to force a sale to a U.S. owner, the app’s fate could hang on whether it’s worth anything without its algorithm, which the Chinese government is threatening to hold hostage.

In hearings, lawmakers zeroed in. “Can you tell me who writes the algorithms for TikTok?” California Democrat Anna Eshoo asked TikTok’s CEO. Republican Troy Balderson of Ohio said, “Your algorithm continues to promote harmful content. Wouldn’t you agree that indicates there is something inherently wrong with the algorithm?”

Through “the algorithm,” TikTok was made alien twice over, an unknowable machine manipulated by a foreign power. Initially, TikTok leaned into this story of algorithmic power, intrigue, and mystery. The narrative may have worked too well. It was also never quite true in the first place.

Without Musical.ly, acquired in 2017, TikTok wouldn’t be TikTok. It launched with millions of users migrated from Musical.ly, whose founder, in 2016, described the platform’s growth in distinctly human-centric ways: “The most important asset of a social network isn’t the content but the social graph,” said Alex Zhu, who later served as TikTok’s CEO. “Because so many creators, they connect with each other and form a social graph.” Musical.ly’s growth wasn’t based on algorithmic recommendations but on the same social-networking effects that built Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

After the acquisition, the algorithm became central. ByteDance signaled the shift as it merged the two apps, spotlighting “a ‘For You’ feed that uniquely serves a curation of personalized video recommendations based on viewing preferences.” The “For You” page has since become synonymous with TikTok as social graphs receded. It began as an experiment — would users respond better to infinite personalized recommendations? — but was also subordinate to a larger corporate strategy. ByteDance, which had created the algorithmic news aggregator Toutiao and TikTok predecessor Douyin in China, marketed itself as an AI company. “Artificial intelligence powers all of ByteDance’s content platforms,” a company spokesperson told The Verge in 2018. “This enables us to serve users with the content that they find most interesting.”

These claims contained some truth, but TikTok’s success was less about the sophistication of its recommendations than how assertively it made them. Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube had been using machine-learning methods to recommend content to users for years — long enough, in fact, that they had each been the subject of intense criticism around the priorities of the algorithm. Facebook’s algorithmic recommendations had been accused by Barack Obama of tearing the country apart; Instagram’s had been blamed for worsening depression; YouTube’s were radicalizing young men with conspiracy content. Where these networks were luring users out of their social graphs with algorithmic recommendations to juice engagement, TikTok made the bet that such recommendations could be a social app’s primary experience.

What was most striking about the app to people who actually used it was how blunt and brazen it was about what it was up to. It was hyperanimated, noisy, and filled with large numbers that implied growth; it spewed notifications without reservation. Its videos were short, played automatically, and never stopped coming. Algorithmic recommendations were, to other platforms, a supplemental late-stage growth hack. TikTok felt like it was all growth hacks — a product unapologetic about its intention to make users tap, scroll, post, and watch as much as possible, for as long as possible, by any means necessary.

I found it strange when people described TikTok’s recommendations as creepy or as evidence that the app’s algorithms knew us better than we knew ourselves. Using TikTok was, for me, defined by encounters with randomness combined with a sensation of surveillance. It showed us unexpected stuff, then narrowed it down based on what we watched. The mystery of TikTok was never the algorithm but rather the user’s willingness to take bait, over and over, until it became a meal. To use it was to confront the feeling of being a test subject in exchange for entertainment. Ascribing TikTok’s appeal to the algorithm was comforting — at least compared to the alternative of accepting that it “knows” you only somewhat more intimately than a slot machine, yet you can’t stand up.

The U.S. social-media giants hadn’t exactly been precious about their growth strategies, but their users were still accustomed to seeing posts from people they knew. What allowed TikTok to surge had less to do with the power of its recommendation algorithm than with its competitors’ inability to instantly and completely turn their platforms inside out, bringing pure engagement-based recommendations into the center of the user experience. In the past few years, of course, they’ve gradually done exactly this — just open Instagram or Facebook or X or YouTube. Mark Zuckerberg is in the process of remarketing his company as an AI firm not unlike what ByteDance did.

Once it was clear that TikTok had in some way beaten its U.S. peers, ByteDance began to experience its own variety of algorithmic backlash. Soon it started to disown its exceptional algorithmic success story. “Recommendation systems are all around us,” the company wrote in a blog post in 2020 after Donald Trump threatened a ban. “From shopping to streaming to search engines, recommendation systems are designed to help people have a more personalized experience.” Nothing to see here — just your friendly neighborhood machine-learning outfit.

A more honest account of the app would have acknowledged a few complicating factors from the start: that its video categorization is powered in part by human contractors, which reportedly label videos according to content and emotional sentiment; that it had teams that routinely decided to boost or bury videos under algorithmic cover. It’s too late for that now. TikTok was, like all the other social networks, always in the very human business of deciding what people should see and, like its predecessors, was happy to let the character of the algorithm — a useful black box of automation — take credit for its success, as long as it absorbed blame for its failings and could somehow help contain its contradictions.

The industry playbook for algorithmic backlash is basically to take it — it’s worth the pain. (Meta stock is up almost fourfold since it found itself in the crosshairs after the 2016 election.) But the stakes are higher for TikTok as a company with genuine roots abroad and an all-in bet on a narrative about its algorithm. It didn’t take much effort to recast the secretive algorithm as a weapon — or “digital fentanyl” — making the prospect of a ban or forced sale first plausible, then reasonable, then imminent.

Without its algorithmic mythology, the TikTok ban might have invited a knottier set of questions: Should the U.S. ban Chinese media with state ties? Should it ban more products manufactured by state-affiliated companies? Do users deserve agency here? Instead, bound to its algorithm, TikTok helped recommend itself out of existence.