From Stranger Than Paradise to Broken Flowers, Jim Jarmusch’s films are cultural scrapbooks, jam-packed with references to his favorite music, movies, writers, and artists. His latest, The Limits of Control, is set in Spain and stars Isaach De Bankolé as a hit man in calm, cool pursuit of a target—though Jarmusch says he’s “not as interested in the plot” as he is in the paintings that the killer admires in a museum, or the music on the soundtrack. The movie, which also stars Bill Murray, Gael García Bernal, and Tilda Swinton, was a collaboration between the cinematographer Chris Doyle (famous for his work with Wong Kar Wai) and production designer Eugenio Caballero (Academy Award winner for Pan’s Labyrinth). Caballero’s book of inspirations (click on the slideshow above to see pages with commentary from Jarmusch)—scraps of color, images, drawings, postcards—was the visual log the three repeatedly referred back to. Jarmusch talks about the process.

Let’s start at the beginning. The title, The Limits of Control, is taken from a William S. Burroughs essay.

It’s about language being used as a mechanism of control, but I like the double meaning. Does that mean the limits of our own self-control, or the limits to which people control us? Burroughs was always looking for coincidental connectedness. Our film is kinda built on that philosophy.

It’s also something of an ode to repetition and variation.

The idea of the variations was there from the beginning, because the guy is doing the same things over and over: going to the café, waiting, going to some safe house, waiting, going to the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid to see a single painting each time. It’s an action film without action, a suspense film without the drama of suspense.

The film starts with a quote from Rimbaud.

The poem, “The Drunken Boat,” is about the derangement of the senses. He’s starting a very strange adventure of his consciousness, and the film does that, too.

You were inspired by the movie Point Blank. Why?

I’m a huge fan of Lee Marvin and Angie Dickinson, and it’s one of John Boorman’s strongest films—a masterpiece, I think. It’s based on Donald Westlake’s book—he wrote a series under the name Richard Stark about a character named Parker. And Parker is a criminal who is very, very focused and cannot be distracted. He is samurai-like, in a way. Especially when I was younger, I devoured crime novels by Charles Willeford and James Cain.

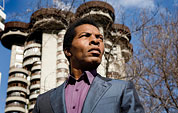

The hit man wears some fabulous suits. Where did they come from?

I’ve been friends with Isaach De Bankolé since 1984. Once, about twelve years ago, he had on this iridescent fitted suit. I was like, “Damn …” He looked like some kind of gangster, in the best sense. I had that image in my head for years. I follow fashion design, and I liked Tom Ford’s fitted men’s-suit look, so I asked him to do it, but he was swamped. So we had a great costume designer who found an amazing tailor in Madrid—an old guy—and I’d go in there every few days, saying, “It’s a half an inch too short, the jacket.” Or, “No, I wanted the pockets Continental style.”

What references did you talk about with Caballero?

We talked endlessly about photographs, paintings, things we saw on the street, music and books and Neruda.

Why Neruda?

This film is about the trip. I’m more interested in the plate of pears on the table than the plot payoff. Neruda, he wrote all these odes to ordinary objects, like “Ode to an Artichoke.” And they are incredibly beautiful poems.

They’re very funny, as is this film.

One of my favorite quotes is Oscar Wilde saying, “Life is far too important to be taken seriously.” You gotta realize my poetry teachers were Kenneth Koch and David Shapiro, and the New York School is very close to my heart. Frank O’Hara was always putting funny things in the poems. Sometimes the poetry is in the silly thing, the funny thing, the offhand thing; it’s not always in the heavy thing. There’s an end of a Frank O’Hara poem that’s “My heart is in my pocket / It is Poems by Pierre Reverdy.” He’s kind of a minor twentieth-century French poet, but O’Hara meant it. There’s something so exuberant to that. And there’s something in this film that celebrates the artifice of cinema too. It’s certainly not a neo-neorealism sort of film. Tilda Swinton’s character represents some kind of angel of the artifice of cinema for me.

Like all your soundtracks, this one is integral to the mood and very unpredictable, with everything from Schubert to trippier stuff by bands like Boris.

I was listening to Boris, thinking of it as edited into a score. There’s one piece of music of theirs with Michio Kurihara, who’s a guitarist from the band Ghost, called “Fuzzy Reactor.” When I was writing, I put it on repeat. It had a psychedelic density to it. I was trying to find music that engendered that kind of slightly altered consciousness. Chris Doyle and I talked about making a film that was mildly hallucinogenic in some cumulative way—almost like a drug. As images accumulate, you gradually start looking at mundane things in a different way.

There’s quite a lot of flamenco—at one point the hit man goes to a performance. We started with one song from the fourteenth century, and I wove that lyric throughout the film: “He who thinks he’s bigger than the rest should go to the cemetery. There he’ll find what life really is: It’s a handful of dirt.” And we used Peteneras, which is kind of the flamenco equivalent of blues. The dancing isn’t a lot of foot-stamping, it’s slow motions. Peteneras is taboo among flamenco people; a lot of bad luck is associated with it. But nothing bad has happened yet …

Peteneras looks like t’ai chi.

La Truco, the dancer we worked with, actually teaches a class which she calls t’ai chi flamenco. When she told me that, I started laughing and told her that we have a lot of t’ai chi in the film. The whole film is built on connections that sort of circumstantially presented themselves.

Hiding in Plain Sight

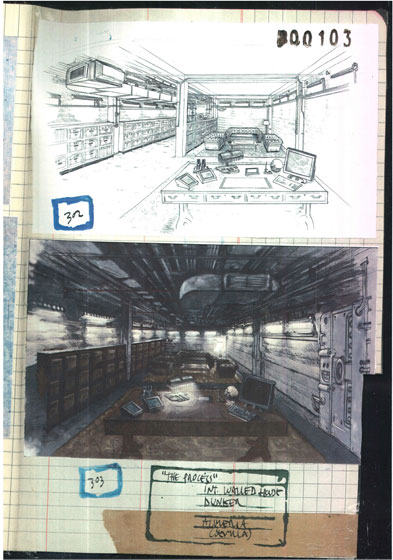

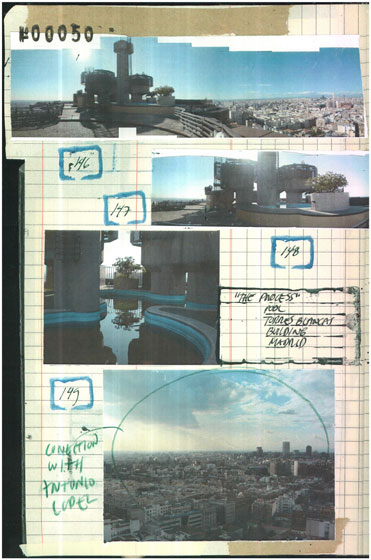

The film’s dapper hit man (Isaach De Bankolé, above) has a conspicuous hideout in Madrid: Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza’s Torres Blancas, a bizarre apartment building that has fascinated Jarmusch for decades. “Chema Prado is the director of the Spanish Cinematheque, and we’re film-freak friends from way back. He’s lived in this building for years,” says Jarmusch. “It’s called Torres Blancas—White Towers—and it’s amazingly strange, though I’m not sure I’d want to live in it. The owner ran out of money when it was built in the late sixties, so instead of white marble on the exterior, they ended up using brown concrete. Each apartment is configured differently, and the building has all these curves.” (And the curves don’t end there. Pictured, above, in a page from Caballero’s book of inspiration, you can see how the sinuous rooms on the bottom—an empty apartment in Torres Blancas—were transformed into the hit man’s hideout. In one scene, he finds a surprise in his round bed, in the shape of wildly curvy actress Paz de la Huerta.)

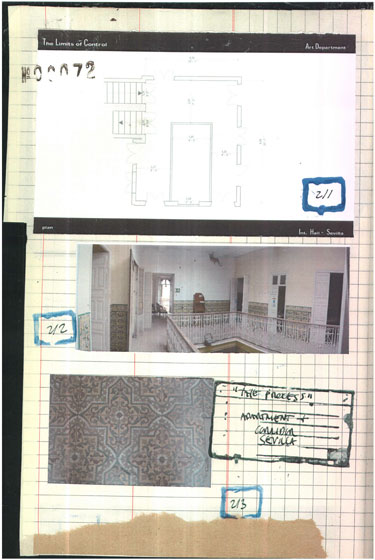

Jarmusch: The Production Journal (All photos: Eugenio Caballero/Courtesy of Focus Features) “Our production designer, Eugenio Caballero, won an Academy Award for Pan’s Labyrinth“a totally different kind of film”but we were just so much on the same plane. He made this fantastic production notebook and I hope someone publishes it: scraps of color, images, drawings, postcards taped into it. It was sort of his log book of developing ideas. And then Chris [Doyle] and I would look through it constantly.”

On the Setting “This building, Torres Blancas, has a kind of Point Blank feel to it, but in a Spanish way. That’s just such a rich film. I’ve seen it so many times, too, and I still see something different each time. In the way John Boorman uses the very ugly architecture of L.A., and yet makes something almost Alice in Wonderland about it with the reflective surfaces. There are moments you don’t know if someone’s interior or exterior until they move past some surface. All that kind of stuff we were kind of devouring.”

On the Curves “I’ve always been confused by the idea of right angles in architecture. Why does everything have to have right angles in our culture? Because it fits in there gridlike, Cartesian way of thinking, but people live in yurts, teepees, and things that are circular, which is much more natural and in a way efficient sometimes for heat and stuff. Torres Blancas is made of all these curves, and none of the apartments are the same in it. They used to have a restaurant on the top floor, and there are dumbwaiters in every apartment, so when they built it, the idea was, you could call up the restaurant and your food could come to your apartment. It’s an amazingly strange building, but I am not sure I want to live in it.”

On the Film’s Paintings “One painting is by Antonio Lopez: a cityscape of Madrid. He’s a painter I really love, an amazing painter. He spends fifteen years on each painting. And there’s actually a film about him making a painting of a quince tree in his backyard that Victor Erice made. It’s a beautiful film! He’d actually made a painting from the top of Torres Blancas, but I didn’t use it because the city looks very different now. I found another landscape ” still Madrid seen from a high building.”

On Art “I wanted him to go to a museum, like, four times in the script to look at one single painting and split. I wanted the paintings to echo something in the film, and I wanted them to all be Spanish painters. So I went to the Prado, I looked at Velázquez and all the classical stuff, but then I went to the Reina Sofía, which is their Museum of Modern Art, and I found the stuff that I wanted. I started with a Juan Gris cubist painting, which has a viola in it, which echoes the violin in the film, the shape of the naked girl, the guitar. The second painting is by Balbuena, who left Spain during the Civil War and lived in Mexico. That’s the reclining nude that you see before he goes and then sees the nude girl.”

On the Soundtrack “For the soundtrack, bands like Ghost and Sun 0))) and Earth and Boris had a kind of trippiness that I wanted. I had a kind of file of music from which I hoped to build a score, which we did, except for a little music that my band made for the film. Our band? We play very slow, kind of trippy stuff. I like these bands that aspire to be the slowest bands in rock and roll; I think Sun wears the badge, but Earth is close ” very slow stuff. I also used the Adagio from Schubert’s string quintet, which is so extremely slow, it’s the same thing in a different century. It’s just with a string quintet instead of electric guitars.”

On Painting “The last [painting in the film] is by Antoni Tàpies, who is a Spanish painter who was one of the first to start incorporating found textures of things: dirt, brass, objects. And this is way before Julian Schnabel’s plate paintings. His painting just looks like a sheet, which echoed to the girl in the sheets and that picture frame he looks at in the house: a painting just covered by a sheet. I was just trying to find variations again and echo things throughout the film.”

On Variations “The idea of variations was there from the beginning. Variations are at the heart of human expression. Bach is a master of varying things, probably because he had so many kids and he needed to get paid, and said, ‘Well, I will just use some of that and make something else out of it…’ And then of course Warhol, fashion, architecture, popular music, everything.”

On Bill Murray’s Hideout “The little house in the end of the movie? Joe [Strummer] lived in Spain, near where that little house is, and after he died, his wife Lucinda said to me, ‘You know, every time we drive by this one house, Joe always said, ‘We gotta show Jim this house; he’s gonna film something there someday.’ And then he was gone. But in fact I did.”

On Joe Strummer’s Hideout “When I would visit Joe in Spain, a couple of times he picked me up in this beat-up black pickup truck that on the back said ‘La vida no vale nada.’ We use it in the film. That came from Joe also. At the time, I thought it was just some Strummerism. Then I found out it’s a Cuban revolutionary song. Translated literally, it’s like, ‘Life is worth nothing.’ But it doesn’t quite work that way. A poet said to me years ago, ‘Reading poetry in translation is like taking a bath with your clothes on.’ It doesn’t quite work.”