Whatever Works, Woody Allen’s 40th movie as writer and director, begins with a ghostly visitation from the distant past of Jewish-American comedy, so distant it predates not only Allen’s career but also his birth, in 1935. The lights dim, we see the familiar white-on-black credits unspool in the same font we’ve been looking at for nearly four decades (it’s Windsor Light Condensed, by the way) … and then we hear the voice of Groucho Marx, Allen’s anarchic spiritual grandfather, singing lyrics he first performed in Animal Crackers in the infancy of sound cinema.

Hello, I must be going

I cannot stay, I came to say

I must be going

I’m glad I came but just the same

I must be going

La la.

The words, which seem pipelined straight from the subconscious of the man who decided to put them in the movie, couldn’t be more apt for the story that follows. Whatever Works, which opens June 19, is both a greeting and a farewell, a film that marks Allen’s return to the city he abruptly abandoned, cinematically speaking, several years ago, as well as a reminder that a certain kind of comedy of which he was once the undisputed master has vanished and is being resurrected only because of an unlikely convergence of circumstances. Remember the Woody Allen of the seventies, the guy who several generations of New Yorkers decided was the comedic poet laureate of their era of the city? The man with whom they had a great first date (1973’s Sleeper) that deepened into a full-on relationship (1977’s Annie Hall) and then further enriched itself into true love (1979’s Manhattan), because we always fall in love with the one who makes us laugh? Whatever Works is, in essence, the missing movie from that period—the film that would have rounded out the New York phase of Allen’s early career if only he had made it.

He finally did, by accident. Allen’s last four movies have been shot in Europe, a shift that occurred after 2004’s little-seen Melinda and Melinda. For many New Yorkers, this felt not quite like a jilting but perhaps like hearing that the ex you dumped has fallen madly in love with somebody more attractive than you. There are moviegoers who have held on through each of Allen’s triumphs and missteps; there are others who pine for the entry that will remind them of his “early, funny ones.” Still others have given up. The public’s relationship with him has gone through cycles of recrimination, most notably over the 1992 Soon-Yi Previn scandal, and forgiveness, a sentiment that was exhibited in 2002 when the director stepped unexpectedly onto the stage at the Oscars to extol the glories of New York filmmaking shortly after 9/11. The roaring ovation that greeted him suggested that he, his fans, and the biz were reconciled at last.

And then he departed. Allen insists that this was motivated by economics, not ennui with a city that still felt it owned him. “If it was up to me, I would work in New York frequently, although I’ve gotten a little addicted to working out of the country too,” he said, when I sat down to talk with him and Larry David last month. “But the city is very expensive.” As a result, the 73-year-old, whose movies return only modest grosses and are financed independently, now spends most summers shooting abroad; he prefers to go into production when the couple’s children, Bechet and Manzie, are out of school.

But early last year, facing what turned out to be the false-alarm threat of a summerlong actors’ strike, Allen was forced to start a movie three months sooner than planned. That meant staying in New York with the kids, and without a new script ready, he reached for an old one. A really old one. Whatever Works is a screenplay that dates so far back it was originally written for Zero Mostel, who died the year Annie Hall came out. Allen updated it very slightly (including a voice-over reference to President Obama), but make no mistake: This movie is literally vintage Woody Allen. In fact, it calls to mind a brand of Jewish humor that has, in recent years, been all but scrubbed out—neurotic, depressive, abrasive, excluded. And to serve as its embodiment, he drafted Larry David, the guy who, through six seasons of HBO’s Curb Your Enthusiasm, has done more than anyone—even Allen—to keep that sensibility alive for a generation to whom it’s now almost completely foreign.

In Whatever Works, David, in what will inevitably be called “the Woody Allen role,” plays physicist Boris Yellnikoff, a cranky, forlorn, impatient New York Jew of a certain age who falls hard for a much younger woman, the sunny but unformed Melody (Evan Rachel Wood), after his marriage collapses in the wake of his general soul-sucking unpleasantness. Boris is a walking disaster—an arrogant snob who sees life as “a chamber of horrors,” derides his uneducated girlfriend as a “submental baton twirler” and “stupid beyond all comprehension,” who refers to another character as a “bigot moron,” and who sneers at the audience in an Annie Hall–style, breaking-the-fourth-wall moment: “I’m sure you’re all obsessed with any number of sad little hopes and dreams.” The movie begins and ends with separate suicide attempts by defenestration; given Boris’s staggering misanthropy, some moviegoers may root for the pavement to win. (Allen didn’t want to play Boris himself, feeling he was too old—David is 61—and may have lacked the character’s natural aggression.)

The picture that results is, anyone would concede, strange—a Larry David movie that doesn’t quite feel like a Larry David movie and a new Woody Allen movie that isn’t really new. Nonetheless, it’s Woodyish enough, and Larryish enough, to make you wish that Allen—who doesn’t appear in the movie—had contrived a way for the two of them to share the screen, emperors of adjoining comedy galaxies finally colliding. To watch the movie is to witness the Jewish man as funny–sad–barely functional Gloomy Gus come to life again and also to wonder if that guy still has any relevance in an age when American Jews don’t feel so bad about things, except on Yom Kippur.

For Boris, the only possible consolation for existential hopelessness is romance: “My story is, whatever works, as long as you don’t hurt anybody,” he says as the movie starts. When I ask Allen if the line represents the Weltanschauung of his thirtysomething or current self, he says his outlook hasn’t changed: “Yes, whatever works to get you through is fine, and not necessarily in relation to relationships. If it’s collecting stamps obsessively, or listening to ball scores, if you’re not encroaching on anyone else, then that’s what you have to do. I think from a philosophic point of view, existence is a nightmare. If you are honest with yourself, it’s a painful thing to go through. You know, the time goes.” He pauses, winces, shrugs. “And then, it stops.”

This, by the way, is why people tend to confuse him with his characters.

Before going further, let us note a complication: Neither Allen nor David sees anything particularly Jewish about their comedy. Perhaps that’s not entirely unexpected given that Allen has always cited Bob Hope as a seminal influence, but, to steal a phrase from Saturday Night Live’s Seth Meyers: Really?!

“Right,” Allen says politely. “You know, it’s funny. I have a blind spot there. Because I wouldn’t see what I do as Jewish humor. I would see it as funny if you think it’s funny, or not if you don’t. But I never think of it as Jewish in any way. Now, as I say, this is a blind spot. Because you and other people might feel differently.”

“I get the same thing,” says David, laughing. “People, you know, Jews, they come up to me, they go, ‘Hey, I’m a Jew—I get it.’ ‘I’m a landsman—love your show!’ Jews want to be the only ones who like it! They think it’s for them. It’s not just for them. And I don’t think that way either.”

Fine. But at least in the secular sense, Allen’s and David’s comic style is Jewish to its marrow. (And as Lenny Bruce famously said, “To me, if you live in New York or any other big city, you’re Jewish.”) If that kind of humor is vanishing, the reason may be that it emerged from a combination of pain and pride that now seems more historical than contemporary. Jewish humor has always struggled between extremes: The excluded outsider is also the smarty-pants; self-mockery tussles with self-aggrandizement; the prideful intellectual is also a slave to his basest appetites and most uncontrollable bodily functions. And every era has found its own mode of angst. The often cruel jokes of a century ago about the anxiety of being a greenhorn from the shtetl with an old-world accent gave way to the urban anxiety of the first-gen Americans running small businesses, which in turn gave way to the suburban anxiety of their children, who were enjoying the American Dream but still couldn’t get into the country club. “ ‘My wife won’t have sex with me! I’m gonna die tomorrow and nobody cares! Everybody’s trying to rip me off!’ ” says Sam Hoffman, creator of the delightful new website OldJews TellingJokes.com (see here), a growing archive of alter kocker humor. “These are the fears of somebody who’s one generation removed from the village and is now in America in the middle of the twentieth century.”

It was in that fifties moment, when self-effacement and self-abasement, paranoia, pessimism, and the dread of being conspicuous were defined as the cornerstones of Jewish humor, that Allen, still in his teens, cut his teeth professionally. Growing up in Brooklyn, at a time when a Jewish-comedy sensibility thrived in movies and nightclubs, on radio and TV variety shows, Allen began as a gag writer, selling one joke at a time, then landed a job writing for Sid Caesar.

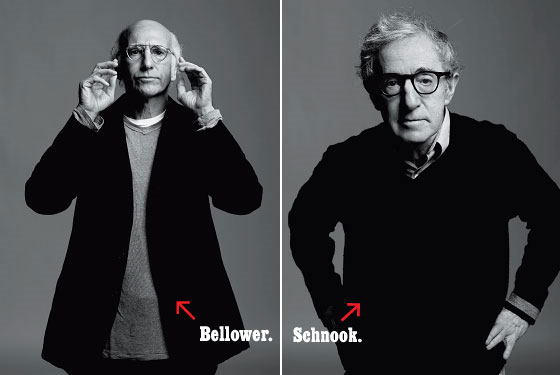

Being faster and sharper than everyone else around you could make you funny, but also outsize and sometimes a little grotesque, or even a lot grotesque (think Uncle Miltie in a dress or Jerry Lewis in buck teeth). Allen’s more understated style opened up a new possibility. In the modern Semitic-comedic golden age that lasted from World War II until the end of the seventies, two Jewish personae ruled: the schnook and the bellower. Allen was the Atlas, or maybe the Job, of schnookdom (a class that also includes Albert Brooks and Richard Lewis); he could elaborate the archetype into a hundred different subcategories, from the philosopher-schlemiel (“Most of us need the eggs”) to the sad striver at romance to the joyless nudnik of Hannah and Her Sisters, always running in petrification to the doctor because of a spot on his back (“It was on your shirt”). On the other hand, the bellower (Mel Brooks; Zero Mostel; shades of Howard Stern; and many, many shades of Larry David) is what Allen describes as the bombastic neurotic— the guy with no volume control or sense of boundaries, the man so uncomfortable in his own skin, not to mention in the company of genteel Gentiles, that he threatens to unleash chaos just by saying the wrong thing, the only skill for which he has an unerring talent.

This either-way-you-lose equation—ingrown depression or jabbing aggression, tic-ish agitation or unsocialized anarchy, Felix or Oscar, choose your poison—used to be essential to a brand of Jewish comedy that mined laughs from the act of chafing against everything you felt excluded from, less worthy than, or insecure about. (Rodney Dangerfield was in his forties before he found his fame-making gimmick, and that “I don’t get no respect” was the expression of an underlying truth that many Jews believed about their place in non-Jewish America.) It didn’t matter if everyone was laughing with your pain, or at it: Take my strife—please!

In the sixties, when Allen began a successful career as a stand-up, he refined the schnook in a way his predecessors hadn’t (perhaps the culture hadn’t allowed them to): He gave the character both intellectual dimension—he wasn’t afraid of looking or sounding smart and culturally literate—and, perhaps more important, the spirit of a romantic. By the time Allen came to prominence as a moviemaker a decade later, his version of the schnook had grown into something deeper and more complex than Jewish-American humor had previously accommodated—a guy who was accepted by the world but not by himself, someone whose kvetchy woe was connected to high-mindedness, to having standards that nobody else lived up to. (From Manhattan: “You think you’re God.” “I’ve got to model myself after someone.”)

Allen wedded the character to an impassioned view of New York City as the only possible playground for that kind of obsessive thinking—a view that not only flattered all of us but also found a way to unite a class of fans by geography and sensibility rather than age or background. “It’s totally Jewish humor,” says writer-director Noah Baumbach, 39, “but it also brought me into a Manhattan that I wished I could live in. There was something about the way he complained about things, and had all these rules and ethics, what bothered him, what was wrong with the city, what was right with the city, what behavior was and was not acceptable … it was very appealing to me. In Manhattan, when he talks about his favorite things … I mean, I had never read Sentimental Education, I had never been to Sam Wo’s and had the crab, but I took those things and owned them. When I was 17, I thought Annie Hall was my story.”

“David discovered a place where an American Jew can still feel like an exile. Just like the good old days!”

To understand why that particular flavor of urban Jewish comedy seemed to vanish so quickly after Annie Hall and Manhattan, even as New Yorkers young and old held it dear, it helps to remember that Allen walked away from it first. In the eighties, he did his Fellini movie (Stardust Memories), his cheery Bergman homage (A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy), his claustrophobic dramas (September and Another Woman), his trifles (Alice). Jewish humor—the gags, the one-liners, the cheerful vulgarity, the tsuris—seemed to become old hat to him; tellingly, when he wanted to give it some play, most of the time he did so in period (Radio Days). When he returned to contemporary New York, most successfully in Hannah and Her Sisters and Crimes and Misdemeanors, he kept to the margins, deploying himself as minor comic relief. The schnook was no longer the center of Allen’s writing or his thinking—or his movies.

Jewish-American comedy needed to grow elsewhere, and in the nineties, Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld stepped into the void left by Allen. Seinfeld, born in 1954, was, generationally speaking, the genre’s logical next step—a New York guy who had, God knows, his quirks, idiosyncrasies, and concealed pockets of insanity yet was also presentable, functional, and, in the most meaningful transformation, fundamentally happy. Seinfeld brought his own well-honed comic persona to his NBC series, but one can feel the hand of Larry David in the ensemble around him. Seinfeld basically split the Jewish comic persona into three distinct branches: Jerry got the jokes, the brains, and the girls. Jason Alexander’s George Costanza (half-Italian and half-Jewish but in every way a member of the Tribe) got the neurosis, the defeat, the exclusion—he was a schnook and a bellower. Kramer (Michael Richards, again Jewish in spirit if not in text) embodied the dangerous unpredictability and the chaos. And every once in a while, of course, we’d step back one generation and visit George or Jerry’s families, the brutal comic implication being, yes, we have our problems, but look at the madness we came from—can you believe we made it out alive?

By the time Seinfeld became a hit, the idea of otherness, or even of depression, as central to Jewish comedy already seemed quaint. And today, in the age of Jon Stewart, it feels downright ancient. Stewart can be smart, impassioned, engaged, shticky, earnest—but neurosis, into which he playfully dips, isn’t the most deeply felt aspect of what he does. When he assumes the stance of a wimp or a weakling, it’s lightly ironic, a costume from the Jewish past he can don for a laugh, then shrug off.

At the movies, Allen’s most natural heir and the most successful representative of the new Jewish humor is Judd Apatow, who has pointedly put Jewish characters in many of his mainstream comedies (a genre that tends to omit potentially discomforting details like religion). To those of us raised on Allen’s films, Apatow’s schlumpy, relaxed good guys may hardly seem Jewish at all—they’re more defined by their status as slackers, stoners, horndogs, and underachievers. They might have grown up asking the Four Questions at the Seder table, but they wear their religious heritage with a casualness—neither obsessive nor dismissive—that is light-years from the scratchy suit in which Allen seemed trapped. “Fuck you guys, I’m glad I’m not Jewish,” grumbles the excluded-feeling non-Semite in Seth Rogen’s Knocked Up posse. “So are we,” Rogen shoots back with a smirk. “You weren’t ‘chosen’ for a reason.”

Even fifteen years ago, some comedy elders might have derided the, let’s call it, Reform Jewish humor of Stewart and Apatow (and Rogen, Sarah Silverman, Adam Sandler, and countless others) as “assimilationist.” Today, the charge is irrelevant. The new comics haven’t assimilated; rather, they were born into a comedy culture that has Jewish humor so deep in its DNA that they’re naturally at home in it. They don’t stand outside anything—except, that is, the set of assumptions that ruled their parents’ generation (success means blending in) and their grandparents’ generation (there are some things you just don’t joke about). When Silverman, for instance, remarks that her grandmother got a “vanity” tattoo at “one of the better concentration camps” (“It said BEDAZZLED”), she’s not only transgressing by making a Holocaust joke but also by assuming a persona—a vaguely homophobic, vaguely racist Jewish-American princess who’s so self-absorbed that she’s oblivious to the effect she produces—that is, to dust off the old phrase, officially bad for the Jews. (On the other hand, she wears her identity so boldly that nobody will ever accuse her of trying to pass.)

Silverman may be an extreme example, but the way Stewart slips in and out of a “Jewish” accent with the dexterity of Oprah Winfrey toggling between her “black” and “white” voices within a single sentence, the ease with which Apatow throws the Jewishness of his characters into scripts as a piece of information rather than a personality trait, and the ability of Sandler to get Hollywood to let him spend a movie playing with an Israeli stereotype in You Don’t Mess With the Zohan are all markers that the old rules have been tossed entirely.

It used to be unspoken that there was a tough, stinging style of humor that Jewish comedians aimed at Jewish audiences (who, like any ethnic group, loved being tweaked for their own idiosyncrasies when nobody else was around to hear) and another, less rough-edged style you brought out for mixed company. With those distinctions eradicated and Jewish comedy now dominated by a generation that never felt like the embodiment of otherness, is there still a home for old-world comedy?

There’s probably nobody who has come up with a cleverer answer to that than David. Curb Your Enthusiasm is by leagues the most successful current example of the sore-thumb style of Jewish humor, as Larry David, playing a guy called Larry David, hangs out, schmoozes, mopes, gripes, grimaces, offends, and generally makes life miserable for everyone around him. One of the most brilliant aspects of the show, which is soon to go into production on a seventh season, is that David, almost alone among his peers, has figured out a way to make Jews into outsiders again—by moving them to Los Angeles, where what makes them alien isn’t Christianity (although TV Larry is in a mixed marriage), but the health, youth, optimism, relaxation, and cheerfulness with which Hollywood proudly defines itself. He’s discovered a place where an American Jew can still find a way to feel like an exile. Just like the good old days!

That may be why, when word spread that David would star in Allen’s new movie, lovers of the Jewish humor that roots itself firmly in misery got so excited. Allen’s gloom tends to turn inward and almost physically shrink him; David’s sprays outward, forcing everyone to step back and allow him a perimeter of clamorous exasperation. How would these two come together?

They almost didn’t. David had had a couple of bit roles in Allen’s movies in the eighties—he’s in one shot in Radio Days, and he and Allen have a swift but pleasing exchange in New York Stories. “But I opened this script up,” says David, “and there’s Boris all over page one. I turned to page 50, and there’s Boris. I went to the last page and saw that Boris had a big speech. And I thought, I need to tell him I can’t do this, really. I called and said, ‘I think you’re under the wrong impression about my acting from the show, because it’s all improvised, and it’s all in my wheelhouse. I haven’t really played a character before.’ ”

Allen told him he’d be fine; he even encouraged David to leap away from the screenplay and improvise. But David arrived determined to stick to the script, retreating to his trailer to memorize lines between scenes. Both men were, in a way, now strangers to a New York that they’d left behind, and had a desire to return to a crankier, more Balkanized version of the city. When Boris’s bourgeois, upscale (read: assimilated) domestic life on Beekman Place falls apart, he retrenches and moves down the ladder. Allen’s seventies draft had placed him in the Village, but this version relocates him to a part of the Lower East Side bordering Chinatown that’s remained untouched by decades of hipsters, gentrifiers, and real-estate opportunists, a land of knishes and kvetches and guys with bum legs and creaky jokes. For New York Jews, it’s the old country—the original Zip Code of existential gloom.

Allen and David don’t know each other that well, but watching them watch each other during a joint interview, it’s easy to imagine where they found common ground during production—in the joy of glumness. It’s hard to mourn the passing of a style of comedy that was based almost entirely on suffering, but let’s be honest: Jews have always been really good at making suffering funny, whether it’s over the oppression of a people or a bad piece of whitefish. Nobody has gotten more mileage out of this than these two, so it’s strange to suddenly see them as custodians of a dwindling tradition. One can feel excited about their comedic descendants and still wistful about the passing of the torch. For now, let’s just be glad that neither man has decided to give up and become happy. “I don’t feel that I’m pessimistic,” says Allen. “That’s something I get called: pessimistic, nihilistic, cynical … I don’t see it that way. I just have a realistic attitude, and the hard facts are so brutal and terrifying that each person has his own way of rationalizing that it’s not so bad. But it is so bad. And the trick is to acknowledge that, and still get through.”

As Allen speaks those words, David starts laughing (where others might weep). “I agree with that,” he says. “I go through life feeling sorry for pretty much everybody. I’ll pass a toll, and I’ll think about the toll collector standing in there for eight or ten hours a day—how do they do it? How do they get up in the morning and go back? I feel sorry for everyone.”

The subject turns to the eventual DVD of Whatever Works. Allen’s movies never come packaged with extras—considering what a nostalgist he is, it’s remarkable that he’s never felt like rewatching even one of his movies after it’s left the editing room, let alone used the occasion of a DVD release to open up his process to audiences.

Woody: “They’re called outtakes because they’re out of the movie. And I don’t know why anyone wants to do the commentaries.”

Larry: “I hate them. I did them once, and I’d never do it again.”

Woody: “This is the thing—”

Larry: “And by the way? When I’m watching, I’m enjoying it and I’m thinking, I don’t want to interrupt with my chatter. I’m intruding on this!”

Woody: “I agree with Larry. You make the film, and it’s the film that you’re selling. You’re not selling your comments.”

Larry: “The sad thing is that people get more interested in the commentary about the movie than the movie itself.”

Woody: “And I can’t work my DVD player. Only my wife can do it.”

Larry: “I can’t do it either. I think maybe that contributed to my divorce.”

The evening before our conversation, Whatever Works had made its debut as the opening-night attraction of the Tribeca Film Festival. Over a thousand people filled the Ziegfeld (apparently, Tribeca now extends to 54th and Sixth), and Allen, though he didn’t introduce the movie, at least showed up, which is impressive in itself. In his standard mufti of tweed jacket and baggy khakis, he flinched and shuffled along the press line, posing for pictures with Previn, with David, and with the film’s co-stars Evan Rachel Wood and Patricia Clarkson.

Allen says that the persistence of some in interpreting his movies as chapters in an ongoing autobiography has been “one of the banes of my existence.” But even if you accept that his fictional creations aren’t him, the similarities are tough to ignore. Check out the red-carpet pictures from that evening: His expression is 30 percent good soldier and 70 percent “get me out of here” queasy hypochondriac. Now try not to think of Annie Hall’s Alvy Singer working himself into a malingering lather in order to wuss out of an awards-show appearance.

It was a friendly house, and the appreciative chuckles began almost as soon as the opening credits ended and David launched himself into the first of his foaming-at-the-mouth fugues. “You are a very difficult man to live with!” Boris’s exhausted wife tells him just before he jumps out the window. Now that’s (Jewish) comedy—a long-lost, brined-in-pickle-juice message in a bottle. The capacity crowd greeted that kind of despair as an old friend, and their laughter had a late-middle-aged timbre, the happy-sad sound you hear when people witness the opening of a time capsule and see something that’s both right in front of their eyes and long gone. It was as if a collective agreement had been made to commune one more time with that old bleak magic before walking back out into a city that has left it behind.

Allen didn’t hear the laughter. By then, he had disappeared again, fleeing the theater before there was the slightest risk of his seeing a frame of his postcard from the past. Hello, he must be going.

See Also

• The Evolution of Jewish Humor

• A Sampling of Old Jews Telling Jokes