What a run this millennium for Pedro Almodóvar: one strange and fabulous feature after the next, each in a different style, each so deftly controlled that you hardly register its subversiveness until after you’ve been hooked by its story. Each film skirts tragedy. In his female-bonding tearjerker All About My Mother, women (in Almodóvar’s universe, the label includes transvestites and transsexuals) cluster together for warmth after the death of the heroine’s teenage son (perhaps a stand-in for the director himself). Talk to Her, which centers on a transgressive love, is flabbergastingly matter-of-fact in its acceptance (as opposed to embrace) of sexual perversity. The noirish puzzle Bad Education gives you flashbacks within flashbacks, stories within stories—each stream circling in on the movie’s final, horrific revelation. Now comes Volver, a surefire crowd-pleaser that takes you back to Almodóvar’s women on the campy verge, but this time in an airy, slyly understated, light-fantastical style. Before it loses its fizz—maybe two thirds of the way through—Volver offers the headiest pleasures imaginable.

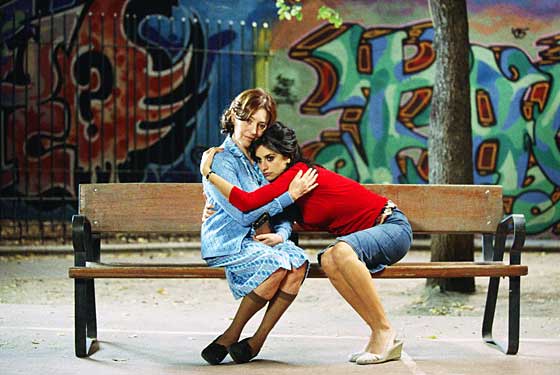

The movie unfolds in a female-centric universe, in which the women keep their families together in the face of male inconstancy—or worse. It’s the old matriarchs we see as Volver begins, the camera gliding past a row of headstones to which they ritually tend, Alberto Iglesias’s music bouncing along rambunctiously, with just a hint of dissonance. Then the camera comes to rest on Raimunda, played by Penélope Cruz—and not the twittering Spanish Minnie Mouse who was Tom’s incongruous appendage. This is a Cruz of substance, of chest tones, of formidable cleavage, a woman completely credible in the role of a bedraggled mother carrying the burden of an unemployed, alcoholic, lecherous spouse and an ingenuous daughter (Yohana Cobo) with no inkling of her budding attractions or sordid origins.

Raimunda has come home to visit her mother’s grave and her elderly aunt, who manages, mysteriously, to clean and cook for herself despite the dwindling of her short- and long-term memory—and much of her memory in between. Rumors abound she’s being cared for by the ghost of Raimunda’s mother, who in due course appears to Raimunda’s sister, Sole (Lola Dueñas)—and is embodied (hooray!) by Carmen Maura, the sprightly ghost of Almodóvar movies past.

In the course of Volver there is a bloody killing and some near-farcical maneuvers with a corpse, but the heart of the movie is the peculiar geometry of a mother, two daughters, and a granddaughter—with plenty of shared dark secrets but no one privy to all of them. When Raimunda takes over (illegally) an empty restaurant near her apartment and conjures up magnificent meals for a film crew, Volver is an oasis of happiness: What could be more ineffably Spanish than a woman (and her female neighbors) performing culinary miracles in the presence of a daughter (the apprentice) and a wistfully maternal ghost? Iglesias’s delightful score (abetted by renditions of Carlos Gardel’s impassioned ballad “Volver”) seems almost free-associative—now puckish, now spare and moody, now lush, with even a dollop of Bernard Herrmann hamminess. The music matches up with Almodóvar’s palette, the colors lit from within but just shy of phosphorescent, the arrival of the supernatural as natural as breathing (and, in this case, farting).It’s too bad Almodóvar can’t keep all the balls spinning. He gets bogged down in backstories—adultery, arson, incest—and puts too much weight on a terminally ill neighbor (Blanca Portillo) whose mother has vanished. He knows what he’s doing: He’s trying to ground the movie and work through all the permutations of ¬mother love, with its irrational rivalries and favoritism and anger over abandonment and a guilt that might even transcend death. But Volver is so much better when it’s glancing and suggestive, when it’s an inspired—and unpredictable—mix of mysticism and earthy comedy. In one scene, a memorial service shot from on high, a group of old women in black pray out loud and shake their black fans and alarmingly converge—a sea of murmuring mothers—on the poor, bereft Sole. That’s the kind of place Volver should have been at the fade-out: haunting and transcendent and more than a little nuts.

Death of a President is a documentary from the future, made—supposedly—a year and a half after the assassination of George W. Bush. It sounds like a piece of incendiary sensationalism, but it’s anything but. The film, directed by Gabriel Range from a script he wrote with Simon Finch, attempts to extrapolate from our present course in the driest and least sensationalized way. Mixing existing footage of the president with (fictional) talking-head interviews, the film depicts how protests in Chicago over the war in Iraq (and sundry other international crises) led to pandemonium, and police brutality led to someone plugging Dubya full of holes. Under President Cheney, the evidence is cherry-picked to place the blame for the assassination on a large Middle Eastern country, and while plans for invasion are drawn up, the executive branch puts the kibosh on civil liberties and all the other niceties of our checked-and-balanced democracy.

Is Death of a President plausible? As political prognostication, perhaps. As a TV documentary, no way in hell. What’s missing is shapeliness, suspense, narrative cunning, visual flair—in short, art. Are we really to believe that a network of the future would broadcast such a barbiturate?

BACKSTORY

The Met’s Peter Gelb recently said that Pedro Almodóvar turned down the opportunity to direct an opera, but Almodóvar tells us, “I think as part of my career as a director, I will do theater.” He’s recently been advising David Leveaux’s stage production of All About My Mother in London. “I’m treating this experience like my apprenticeship, so I’m very present in this process, just to learn. [Film and theater] are two very different disciplines, but both are based in acting, which is the part that I like, more than to make a movie. I really want to make something for the stage.”

SEE ALSO

Memory Banker

Logan Hill’s interview with Pedro Almodóvar

Volver

Directed by Pedro Almodóvar. Sony Pictures Classics. R.

Death of a President

Directed by Gabriel Range. Newmarket Films. R.

E-mail: [email protected].